Tags

Distinct Society, habitant, James Murray, Language Laws in Quebec, Lord Elgin, Sir Guy Carleton, the Noble Savage, United Empire Loyalists

—ooo—

The Treaty of Paris, signed on 10 February 1763, was a tragic event for the citizens of New France, the Canadiens. Jacques Cartier discovered Canada in 1534, and Port-Royal (Acadie) was settled in 1605, three years before the city of Quebec was settled. Therefore, in 1763, Nouvelle-France had been a French colony for 229 years. In fact, France possessed a large territory in North America, where it barely settled. Canadiens lived on the shores of the St Lawrence River, where they were censitaires, seigneurs, members of the clergy, habitants, and voyageurs. Censitaires paid “cens et rentes” to their seigneur as well as la dîme (tithe) to their curé, Parish priest. They had tilled their “thirty acres” since the early 1620s. Habitants were a new social type. They owned their house, farmed, and some engaged in the fur trade. They were “Americans.” (See Habitant, The Canadian Encyclopedia.)

Le régime seigneurial a engendré un nouveau type social dont il consolide les intérêts: l'habitant indépendant, exempt d'impôt personnel, propriétaire de sa terre, très mobile à cause de la traite et de l'abandonnance des terres, libérés des corvées seigneuriales et sur le même pied que le seigneur vis-à-vis les pratiques communautaires.[1][2]

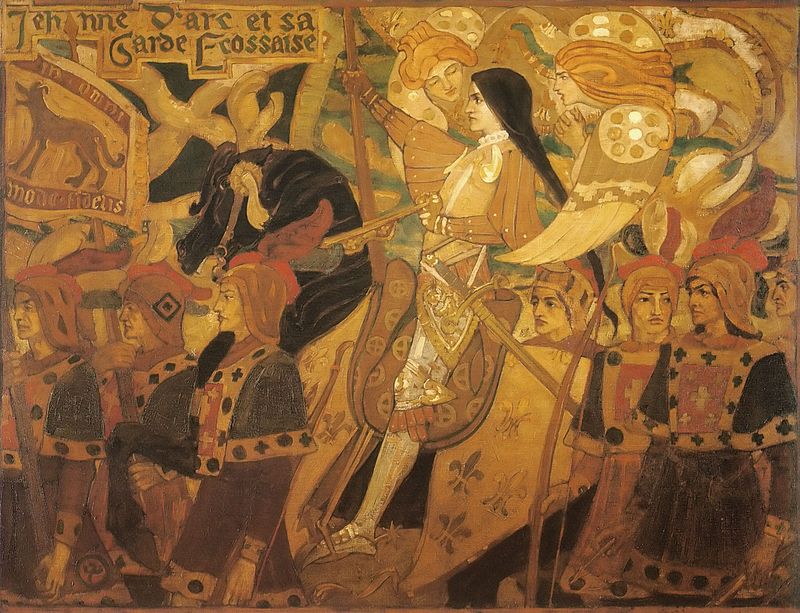

Many were the legendary voyageurs who travelled to the countries above, “les pays d’en Haut” (1610-1763), in canoes Amerindians built. By and large, the people of New France had a good relationship with future Canada’s Amerindians. Given Nouvelle-France’s cold climate, the French needed Amerindians to settle and earn their living. They never colonised the Indigenous people of North America, but sins were committed. Canadiens gave trinkets and alcohol to Amerindians in return for precious pelts. Amerindians guided explorers and voyageurs and opened up the North American continent. In fact, voyageurs married Amerindians. When the beaver neared extinction, the French still went to the countries above, “les pays d’en Haut.” They were bûcherons, lumberjacks, and draveurs, river drivers.

New France exemplifies Montesquieu “théorie des climats,” and, to a large extent, Nouvelle-France is also one of the birthplaces of the Noble Savage. Le bon sauvage is le baron de Lahontan‘s Adario, a Huron.

Le Bon Sauvage also inhabits Philippe-Joseph Aubert de Gaspé‘s Les Anciens Canadiens, a novel belonging to La Patrie littéraire, a homeland of literary and historical works, but also other achievements. Le bon Sauvage illustrates that virtue need not stem from religious convictions, a dilemma for missionaries.

Adario le Sauvage discute avec Lahontan le civilisé; et ce dernier a le mauvais rôle. A l'Évangile Adario oppose triomphalement la religion naturelle. Aux lois européennes, qui ne cherchent à inspirer que la crainte du châtiment, il oppose une morale naturelle. [Adario the Savage discusses with Lahontan, the civilized; and the latter plays the bad role. To the Gospel, he opposes, triumphant, natural religion. To European laws that seek only to instill fear, he opposes a natural moral.][3]

Besides, not only had France been in North America for two centuries, but the Battle of the Plains of Abraham lasted less than a half-hour, and it was fought between uneven forces. Should such a battle cost so much to a nation? New France was a nation. During the Seven Years’ War, France and its allies were waging war against the British and their allies, each side seeking world hegemony.

In the days of empires and colonies, the loss of New France and France’s vast territory in North America was mostly collateral damage Colonies were forgettable. The Duc de Choiseul hoped France would regain its North American colonies, but France “needed peace.” (See Treaty of Paris 1763, Wikipedia.) So, the Thirteen Colonies would soon declare their independence while a foreigner entered New France. The first rule had been to assimilate the French in Canada, and the first résistance would be a struggle to preserve the French language manifested in Quebec’s current language laws. Bill 22, 1974; Bill 101 (the Charter of the French Language, 1977); and Bill 96 (2021). Moreover, the “foreigner” inhabits the mind of members of the Patrie littéraire and Félix-Antoine Savard’s Menaud maîre-draveur (1937), the literary schools created after Lord Durham stated that Canadiens lacked history and literature. Works associated with the Patrie littéraire, the literary homeland listed on Canadiana.2 page.

Jeffery Amherst could not understand the Canadien‘s grief. He was British, and the British had won the war. He would be returning to Britain, which would soon be a large empire. As for France, it would remain France and survive a regicidal Revolution.

Much land that had been owned by France was now owned by Britain, and the French people of Quebec felt greatly betrayed at the French concession. The commander-in-chief of the British, Jeffery Amherst noted, “Many of the Canadians consider their Colony to be of utmost consequence to France & cannot be convinced … that their Country has been conceded to Great Britain.”

(See Jeffery Amherst quoted in Treaty of Paris, 1763, Wikipedia.)

Under the Treaty of Paris (1763), France chose to cede Nouvelle-France, a colony and a province of France. It also ceded land east of the Mississippi River, part of Louisiana. France kept two small islands off the coast of Newfoundland, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. These would accommodate French fishermen. France also kept sugar-rich Martinique and Haiti. The British had won the Seven Year’s War. However, France had ceded a small nation to Britain.

Earlier, in 1713, at the Treaties of Utrecht, or Peace of Utrecht, France had ceded Acadia, one of the two provinces of New France, Newfoundland, and territory bordering the Hudson Bay. Between 1755 and 1758, the British expulsed Acadians. Imperialism was ruthless. The Expulsion may have been caused by conflicts between priests from France and New Englanders mainly. Father Le Loutre’s War lasted between 1749 and 1755, the year the Acadians of Grand-Pré were deported. The map below shows the territory lost in 1713 (mauve) and the territory ceded at the Treaty of Paris in 1763 (blue).

—ooo—

The Quebec Act of 1774: a Period of Grace …

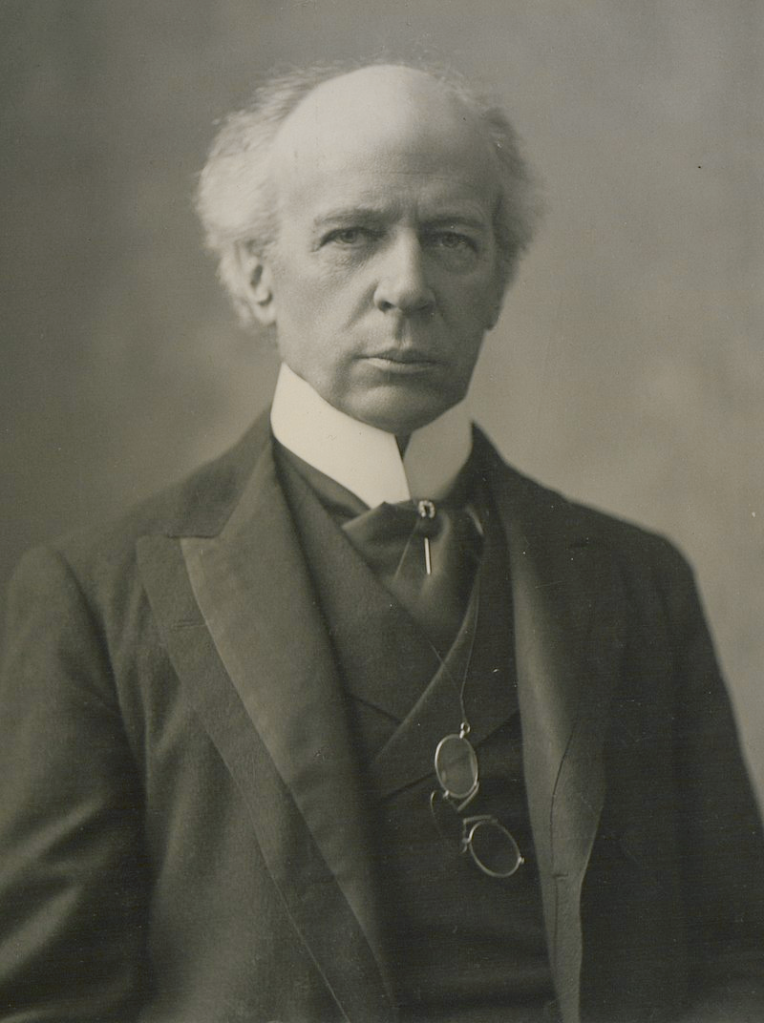

It was not altogether a “period of grace,” but James Murray and Sir Guy Carleton were kind to the defeated Canadiens. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 directed James Murray to assimilate the Canadiens. However, after the Treaty of Paris (1763), only a few British Americans moved to the former New France, so few that many Canadiens did not notice they had lost their land. Besides,

As governor of the former New France, Murray opposed repressive measures against French Canadians, and his conciliatory policy led to charges against him of partiality. Although exonerated, he left his post in 1768 and was appointed governor of Minorca in 1774.

(See James Murray, Britannica.)

These British Americans exacerbated Governor James Murray and Sir Guy Carleton, James Murray’s replacement. Britannica describes these “British Americans” as follows:

Their bourgeois mentality and repeated demands for the “rights of Englishmen” tended to alienate the conservative British officers who administered the colony.

(See Early British Rule, 1763-1791, Britannica.)

Moreover, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 directed James Murray, the Governor of Britain’s new French-speaking subjects, to assimilate the people he governed.

James Murray may have been inclined to spare the Canadiens, who had just fallen. In Philippe Aubert de Gaspé‘s Les Anciens Canadiens, governor Murray is touched when he hears that aristocrats returning to France perished off the coast of Cape Breton island. They were returning to France aboard a frail ship named l’Auguste. (See Chapter XV, Le Naufrage de l’Auguste; Chapter XIV, The Shipwreck of the August.)

No sooner did New France fall to Britain than it attempted to assimilate its new subjects. Governor James Murray failed because the Canadiens were too numerous. Besides,

He [James Murray] was recalled in 1766, but he was exonerated. His replacement was Guy Carleton, (later) 1st Baron Dorchester), who was expected to carry out the policy of the proclamation. However, Carleton soon came to see that the colony was certain to be permanently French. He decided that Britain’s best course was to forge an alliance with the elites of the former French colony—the seigneurs and the Roman Catholic church.

(See James Murray, Britannica.)

Sir Guy Carleton’s Quebec Act, 1774 (Britannica)

—ooo—

Seigneurial System: New France’s River Lots (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

James Murray’s replacement, Sir Guy Carleton, negotiated the Quebec Act of 1774 with Seigneurs and the clergy. It restored the Seigneurial System and excluded the Test Acts. One did not have to renounce Catholicism to enter the civil service or hold public office. It pleased seigneurs and the Clergy, whose income it guaranteed, but censitaires begrudged the Quebec Act. They would have to pay cens, rente and la dîme (tithe), an obligation not rigidly observed during l’Ancien Régime in New France. Except for the conditions of his tenure, there were times when the censitaire showed complete independence in his relationship with the master of the mansion. He did not recognize his authority, and seigneurs exerted no influence on his opinions:

[H]ors des conditions de sa tenure, le censitaire possédait en fait et manifestait à l'occasion une pleine indépendance à l'égard de son maître du manoir. Il ne lui reconnaissait ni autorité sociale, ni emprise sur ses opinions.[4]

Yet, flawed as it was, the Quebec Act of 1774 can be seen as the Bill of Rights granted Canadiens. It placed the censitaires under the rule of seigneurs and the clergy, an unfortunate precedent. But it also put French-speaking and English-speaking citizens of an enlarged Province of Quebec on an equal footing, or almost. In earlier posts, I have compared the Quebec Act of 1774 to the Royal Proclamation of 1763. In both cases, these are letters patent for both Amerindians and the defeated French.

Matters would change. After the American Revolution, United Empire Loyalists, the citizens of Britain’s former Thirteen Colonies who had remained loyal to Great Britain, sought refuge in British North America and elsewhere. United Empire Loyalists wanted to live in Quebec the way they had lived in the former Thirteen Colonies, where their Rights as Englishmen had been recognized. Besides, Quebec’s Civil law (Code civil) differed from the Common law. The Quebec Act was as intolerable to them as it had been to the British Americans who wanted to secede from England.

Although France was defeated at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham and Nouvelle-France ceded to England at the Treaty of Paris of 1763, Guy Carleton, later 1st Baron Dorchester, passed the Quebec Act of 1774. The Quebec Act restored Nouvelle France’s Seigneurial System. Censitaires were disgruntled, but the Quebec Act empowered seigneurs and the Clergy. However, it had been conciliatory with the French, a defeated nation. United Empire Loyalists insisted on redress, which was a legitimate request. United Empire Loyalists had been loyal to Britain and had left their home to remain British subjects. (See Constitutional Act of 1791, Wikipedia.)

As governor in chief of British North America (1786–96), Guy Carleton promoted the Constitutional Act of 1791, which helped develop representative institutions in Canada at a time when the French Revolution was threatening governments elsewhere.

(See Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester, Britannica.)

The British parliament passed the Constitutional Act of 1791. The Constitutional Act separated a down-sized Province of Quebec into Upper and Lower Canada. Most English-speaking citizens would live in Upper Canada under the Common law. Lower Canada would be home to Canadiens and would keep its Civil law. However, Lower Canada’s Eastern Townships would belong to United Empire Loyalists who, initially, did not allow Canadiens to settle in the Townships, a policy that changed when factories opened in the Townships, creating a need for employees. These were French Canadians and the Irish who had been driven away from their homeland by the Great Famine, a potato famine.

Until 1791 the region was organized under the seigneurial system of New France. In 1791 the region was resurveyed under English law. It was divided into counties, which were in turn subdivided into townships. (Eastern Townships, Wikipedia)

(See Eastern Townships, Wikipedia.)

Britannica’s entry on the Constitutional Act of 1791 suggests a “fear of egalitarian principles.” Despite the distance and limited literacy, the citizens of New France were familiar with the French Enlightenment. Louis-Joseph Papineau, who replaced Pierre-Stanislas Bédard as the leader of le Parti canadien, Canada’s first political party, renamed le Parti patriote, had read Voltaire. Louis-Joseph Papineau led Lower Canada’s patriotes during the Rebellions of 1837-1838.

The Act of Union

- Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine

- Lord Elgin (James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin)

French Canadians had feared the union of Upper and Lower Canada. In his Report on the Rebellions of 1837-1838, Lord Durham recommended the union of Upper and Lower Canada. The Act of Union was voted into law in 1840. However, Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine succeeded in creating a bilingual Province of Canada. (See Editorial: Baldwin, LaFontaine, The Canadian Encyclopedia.) Much was accomplished during the “great ministry.”

In 1848, Lord Elgin (James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin) established a responsible government in the Province of Canada. Moreover, Baldwin and LaFontaine passed the Rebellion Losses Bill. It was given royal assent by Lord Elgin. An “English-speaking mob” (See Lord Elgin, Wikipedia) set Montreal’s Parliament Buildings afire. (See Burning of the Parliament Buildings in Montreal, Wikipedia.) The Baldwin-LaFontaine great ministry had created a bilingual Canada.

Confederation (1867)

- John A. Macdonald

- Residential schools

- “Uniform” schools

- French Canadians are minoritised

When Canadian provinces federated, Manitoba had as many English-speaking citizens as it had francophones. However, John A. Macdonald, the father of Confederation, acted as though Canada had just begun. He did not negotiate the entry of Manitoba into the Canadian Confederation. Land surveyors arrived at the Red River unannounced and prepared to transform long, narrow lots abutting a river into square lots. The river was a highway: a canoe in summer, a sleigh in winter, not to mention skating blades. Louis Riel embodies a flawed Confederation. The Canadian government simply arrived. Moreover, in 1867, Manitoba had separate schools, French and Catholic (the French were Catholics) and English. John A. Macdonald also began applying Macaulayism.

In the infamous Residential Schools, Indigenous children were punished if they spoke a native language. So harsh a fate did not befall French Canadians. Still, as Canada unfolded westward, the children of immigrants had to attend “uniform” schools or schools where the language of instruction was English. John A. Macdonald minoritised the French in Canada. Moreover, French Canadians could not leave the province of Quebec if they wanted their children to be educated in French. He, therefore, created the “schools” question and the “Quebec” question. He made the “Canada” question.

In the eyes of Europeans, the defeat of France on the North American continent may have been, as I have named it: “collateral damage.” Although the French and their allies lost the Seven Years’ War. France remained as it was. As for New France, it was a colony in the eyes of European belligerents in the Seven Years’ War, the European theatre of the French and Indian War. Besides, at the beginning of the French and Indian Wars, New France was home to 60,000 settlers. (See French and Indian War, Wikipedia.)

Americans view the French and Indian War as more than the American theater of this conflict; however, in the United States the French and Indian War is viewed as a singular conflict which was not associated with any European war. French Canadians call it the guerre de la Conquête (‘War of the Conquest’).

(See French and Indian War, Wikipedia.)

Comments

Confederation hurt Canada. Minoritising French-speaking Canadians jeopardised their survival. As immigrants arrived in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and elsewhere, their children were educated in “uniform” schools, schools where the language of instruction was English. If Québécois wanted their children to be educated in their mother tongue, they remained in Quebec. It is difficult to ascertain whether John A. Macdonald was aware that he was introducing Macaulayism in Canada, thereby creating the “Quebec question.” He was an Orangeman from Ontario.

Louis Riel was a Métis and a Catholic, educated in Montreal. He is a controversial and tragic figure. He embodies a flawed Confederation and the “schools” question. In 1867, Manitoba had “separate” schools. Moreover, Riel did not expect surveyors to arrive at the Red River ready to cut long and narrow lots abutting a river into square lots. These river lots were used as a highway. During the summer, a boat sat on the river. In winter, a sleigh replaced the ship. These were New France’s river lots.

So, Riel formed a provisional government and allowed the execution of Thomas Scott, which would cost him his life. It is difficult to ascertain whether John A. Macdonald was aware of Macaulayism. In Residential Schools, Indigenous children were punished if they were caught speaking a native language. As Canada unfolded westward, the children of immigrants had to attend “uniform” schools. The “schools” question begins in Manitoba, where language and religion cloud the issue. The French were Catholics. In Ontario, the debate is about language.

The Ontario schools question was the first major schools issue to focus on language rather than religion. In Ontario, French or French-language education remained a contentious issue for nearly a century, from 1890 to 1980, with English-speaking Catholics and Protestants aligned against French-speaking Catholics.

(See Ontario Schools Question, The Canadian Encyclopedia.)

Quebec was the victim of John A. Macdonald’s “uniform” schools or schools where the language of instruction was English. Quebec was the only province where children could be educated in French. So, the children of immigrants to Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and elsewhere entered English-language or “uniform” schools. The “schools” question was fought in Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick and elsewhere. “Uniform” schools created an imbalance. Most Canadians spoke English only.

After Confederation, French Canadians could not leave Quebec if they wanted their children to be educated in French. Consequently, Québécois view Quebec as their province. Moreover, historically, Quebec is the older Canada. Therefore, Quebec passes language laws to build a workplace in Quebec.

A “DISTINCT” SOCIETY

There has been no formal separation of Quebec from Canada, but John A. Macdonald separated Quebec from other provinces of Canada. The “schools” question justifies unilingualism. Besides, Quebec is a “distinct society,” despite hesitancy. (See Quebec as a Distinct Society, The Canadian Encyclopedia.) I doubt that Québécois see Québec as a province. A unilingual province within a bilingual country is a province. However, the view that Quebec is a “distinct” society has often been expressed. But this view has opponents.

In fact, the Supreme Court Act provides that three of the nine judges on the Supreme Court of Canada must come from Quebec, in order to represent the civil law tradition in the Court. (See Quebec as a Distinct Society, The Canadian Encyclopedia.)

RELATED ARTICLES

- Canadiana. I (page)

- Canadiana. 2 (page)

- Language Laws in Quebec, a Balance View (3 November 2022

- A Unilingual Province in a Bilingual Province (29 October 2022)

- Language Laws in Quebec: la Patrie littéraire, the Literary Homeland (2 October 2022)

- Language Laws in Quebec, A Preface (29 September 2022)

- Le Patriote (16 August 2022)

- From Cats to l’École acadienne de Pomquet (25 July 2022)

- On Quebec’s Language Laws: Bill 96 (21 June 2022)

- On Quebec’s Language Laws (18 November 2021)

- The Conquest: its Aftermath (4 August 2021)

Sources and Ressources

https://educaloi.qc.ca/en/ ←

Language Laws and Doing Business in Québec

(Canada, Early British Rule, 1763-1791, Britannica.)

Les Anciens Canadiens (ebooksgratuits.com). FR

Cameron of Lochiel (Archive.org ), Sir Charles G. D. Roberts, translator. EN

Cameron of Lochiel is Gutenberg [EBook#53154], Sir Charles G. D. Roberts, translator. EN

_________________________

[1] Denis Monière, Le Développement des idéologies au Québec des origines à nos jours, Éditions Québec/Amérique, 1977.

[2] Jean-Pierre Wallot, « Le Régime seigneurial et son abolition au Canada » (Canadian Historical Review, l, 4, décembre 1969, p. 375.) (Quoted by Denis Monière, p. 61.)

[3] Paul Hazard, La Crise de la conscience européenne, (Paris: Fayard, 1961), p. 12.

[4] Gustave Lanctôt, Le Canada et la révolution américaine (Montréal: Beauchemin, 1965), p. 82. (Quoted by Denis Monière, p. 103.)

—ooo—

Love to everyone 💕

© Micheline Walker

7 November 2022

WordPress

The Old Smoker, by

M.-A. de Foy Susor-Coté, 1926

National Gallery of Canada (NGC)