Tags

Bill 96, Canada Day, Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom, Language Laws, Les Anciens Canadiens, Multiculturalism, Official Languages Act 1969, Two Solitudes

- Canadiana 1 (page)←

- Canadiana 2 (page)←

Les Anciens Canadiens

I have written several posts on Philippe Aubert de Gaspé‘s Les Anciens Canadiens. I used a translation entitled Cameron of Lochiel. Cameron of Lochiel is the title Sir Charles G. D. Roberts gave to his second translation of Aubert de Gaspé‘s Les Anciens Canadiens (Canadians of Old).

Jules d’Haberville, a seigneur‘s son, and Arché, Archibald of Locheill, a Scot, are close friends. Both are studying at the séminaire (college) in Quebec City and Arché spends holidays with the d’Haberville family. When Jules and Arché leave the séminaire, the two friends join the military and are enemies during the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. Jules is very angry. Arché had to burn down the Seigneur d’Haberville’s Manoir. The two reconcile. Jules will marry an English woman, but Blanche, Jules’s sister, will not marry Arché. These are the two faces of “Canada” after Nouvelle-France‘s defeat. One turns the page, but one remembers. Les Anciens Canadiens is an instance of anamnesis, but it proposes a union between French-speaking Canadiens and English-speaking Canadians.

The former citizens of New France were governed, first, by James Murray and, later, by Sir Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester. We owe Sir Guy Carleton the Quebec Act Act of 1774, a recognition of French-speaking Canadians. The Quebec Act did not fully cancel the Royal Proclamation of 1763, a recognition of the rights of Canada’s First Nations, but it ended a will to assimilate French-speaking British subjects. Similarly, the Constitutional Act of 1791 did not fully repeal the Quebec Act of 1774. Quebec retained its Seigneurial System, which was not abolished until 1854. Moreover, French-speaking Canadians could still speak French, practice their religion, keep their Code Civil, and run for office. However, the Constitutional Act of 1791 reduced the size of the former Province of Quebec and it separated Canada into Upper Canada and Lower Canada (lower down the St Lawrence River).

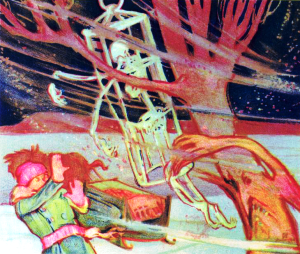

I quoted the Preface to Sir Charles G. D. Roberts‘ second translation of Les Anciens Canadiens in my last post, but my quotation disappeared. The image of Cameron of Lochiel (Arché) had been placed at the foot of this post without reference to Cameron of Lochiel.

Cameron of Lochiel, the Gutenberg Project’s [Ebook 53154]

Les Anciens Canadiens, ebookgratuits.com

Sir Charles G. D. Roberts belonged to a group called the Confederation poets. These poets supported Canadian unity which was dealt a blow by Confederation. However, this could not be discussed in 1905, despite Confederation occurring in 1867. At that point, no one knew to what extent Residential Schools would harm Amerindians. Moreover, in 1905, the imbalance between English-speaking Canadians and French-speaking Canadians could not be assessed. But we read, in Charles G. D. Roberts’s Preface, that “there is afforded a series of problems,” which is a signal.

In Canada there is settling into shape a nation of two races; there is springing into existence, at the same time, a literature in two languages. In the matter of strength and stamina there is no overwhelming disparity between the two races. The two languages are admittedly those to which belong the supreme literary achievements of the modern world. In this dual character of the Canadian people and the Canadian literature there is afforded a series of problems which the future will be taxed to solve. To make any intelligent forecast as to the solution is hardly possible without a fair comprehension of the two races as they appear at the point of contact. We, of English speech, turn naturally to French-Canadian literature for knowledge of the French-Canadian people. The romance before us, while intended for those who read to be entertained, and by no means weighted down with didactic purpose, succeeds in throwing, by its faithful depictions of life and sentiment among the early French Canadians, a strong side-light upon the motives and aspirations of the race.

Sir John A. Macdonald and his followers created the “Quebec Question.” The children of immigrants to Canada who settled in provinces outside Quebec attended “uniform” schools. They learned English, and many grew to believe that Canada was an English-language country. Québécois have been addressing this imbalance by passing Language Laws, one of which is Bill 96. Bill 96 threatens what has long been a reality confirmed in the Official Languages Act of 1969. Canada is an officially bilingual and bicultural country.

These laws have been a source of tension between the two “solitudes,” francophones and anglophones. Hugh MacLennan published Two Solitudes (1945), depicting Canada’s profoundly divided anglophones and francophones. This problem was investigated by the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (1963-1969). However, Language Laws, Bill 96, perpetuate the division between anglophones and francophones. They also project an unfavourable image of Quebec. Moreover, language laws misuse the policy of multiculturalism, first expressed by Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, in 1971. Multiculturalism, or pluralism, is not a cancellation of the Official Languages Act of 1969.

The term multiculturalism is descriptive. It recognizes the presence in Canada of persons originating from many lands, but Canada remains a bilingual and bicultural nation. Multiculturalism cannot be used not to learn at least one of Canada’s official languages. Nor can it be used as a promotion of unilingualism (French or English) on the part of individuals and a government. Moreover, since the passage of the Official Languages Act of 1969, government services should be provided in the two official languages. For instance, a francophone should not be tried in English, nor should an anglophone be tried in French. Finally, Bill 96 cannot compel individuals in Quebec to use French only. If so, it breaches the Official Languages Act of 1969.

Multiculturalism was recognized in Section 27 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982). But, interestingly, New Zealand born and educated Peter Hogg, CC QC FRSC, Canada's foremost authority on Canadian constitutional law, “observed that this section did not actually contain a right; namely, it did not say that Canadians have a right to multiculturalism. The section was instead meant to guide the interpretation of the Charter to respect Canada's multiculturalism. Hogg also remarked that it was difficult to see how this could have a large impact on the reading of the Charter, and thus section 27 could be more of a rhetorical flourish than an operative provision.’” (section 27 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Wikipedia.)

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/air-canada-ceo-french-1.6236356

In a post entitled On Language Laws in Quebec (18 November 2021), I wrote that last November, Air Canada‘s CEO (PDG), Michael Rousseau, who had lived in Quebec since 2007, addressed the Montreal Chamber of Commerce in English. He made Air Canada look like a foreign corporation where business was conducted in the English language. Michael Rousseau’s snafu could be interpreted as a breach of the Official Languages Act, passed in 1969, fifty-three years ago. A friend reminds me that in Canada, French is not a foreign language.

Conclusion

In the 1960s, my father, a favourite guest of talk shows in Vancouver, would be told that the French in North America had lost the Battle of the Plains of Abraham (13 September 1859), which had settled matters once and for all. Such a comment used to sadden me. We are now in the 2020s. It has also saddened me to hear relatives praise a student who attended university in Quebec managing not to learn French. He or she may not have found time to study French and missed an opportunity to do so. Moreover, my career was affected by Quebec’s language laws. I was expected to explain Quebec, which I could not do. Nor could I provide a method of teaching that led to a quick mastery of the French language.

I do not support Quebec’s language laws. They further separate Canada’s anglophones and francophones and create polarisation. People dig in their heels endangering the French language and Canadian unity.

On 24 June, Québécois celebrated la Saint-Jean-Baptiste, Quebec’s national holiday. The celebration is rooted in la Saint-Jean, a celebration of the summer solstice. Canada day is celebrated on 1 July, today. There have been sinners on both sides of Canada’s linguistic divide, but I am celebrating Canada Day.

RELATED ARTICLES

- Language Laws in Quebec: Bill 96 (21 June 2022)

- On Language Laws in Quebec (18 November 2021)

- About Confederation, cont’d (6 October 2020)

- About Canadian Confederation (15 September 2020)

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier: the Conciliator (15 July 2020)

- La Saint-Jean-Baptiste & Canada Day (6 July 2015) ⬅️

- Beyond Bilingualism and Biculturalism (2 May 2015) ⬅️

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier: the Conciliator (15 July 2020)

- The Aftermath, cont’d: Aubert de Gaspé Les Anciens Canadiens (30 March 2012)

- The Aftermath & Krieghoff’s Quintessential Quebec (29 March 2012)

Les Anciens Canadiens

- Les Anciens Canadiens & the Noble Savage (15 July 2021)

- The Good Gentleman (9 July 2021)

- Jules d’Haberville & Cameron of Lochiel (12 June 2021)

- La Débâcle / The Debacle (13 June 2021)

- Les Anciens Canadiens/Cameron of Lochiel (9 June 2021)

- Jules d’Haberville & Cameron of Lochiel (6 June 2021

PAGES

- Canadiana 1 (page)←

- Canadiana 2 (page)←

- Voyageurs Posts (page)

Sources and Resources

- Charles G. D. Roberts: Cameron of Lochiel is an Internet Archives publication

- Les Anciens Canadiens (ebookgratuits.com)

- https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/bill-96-explained-1.6460764

- https://montreal.ctvnews.ca/language-law-bill-96-adopted-promising-sweeping-changes-for-quebec-1.5916503

- https://www.msn.com/fr-ca/actualites/quebec-canada/le-bilinguisme-%c2%ab-laffaire-des-francophones-%c2%bb-dans-la-fonction-publique-f%c3%a9d%c3%a9rale/ar-AAYJhym?ocid=msedgntp

- https://cultmtl.com/2021/05/quebec-and-bill-96-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly-french-language/

Love to everyone 💕

Micheline Walker

1st July 2022WordPress

The Corriveau of Legend is a woman who killed several husbands and was condemned to be hanged and put in chains in an iron cage. She scarred travellers. But there was a real Corriveau, Marie-Josephte Corriveau (1733 -1763).

The Corriveau of Legend is a woman who killed several husbands and was condemned to be hanged and put in chains in an iron cage. She scarred travellers. But there was a real Corriveau, Marie-Josephte Corriveau (1733 -1763).