Tags

Claude Monet, Great Wave Off Kanagawa, Hiroshige, Hokusai, Japonism, Mount Fuji, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, Utamaro

The Great Wave off Kanagawa, by Katsushika Hokusai, 1832 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

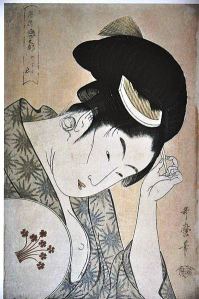

Related Post: Utamaro’s Women & Japonisme- Kitagawa Utamaro (c. 1753 – 31 October 1806),

- Katsushika Hokusai (c. 31 October 1760 – 10 May 1849) and

- Utagawa Hiroshige (1797 – 12 October 1858).

Beginning in the 1850s, the influence of Japonism on European art in general and French art in particular was pervasive. In my last post, I named three artists: Utamaro, Hokusai and Hiroshige. All three were ukiyo-e painters of the Edo period. But there were other ukiyo-e painters and it is still possible to purchase Japanese estampes. Prints belonging to original series executed by our three artists and other masters are very expensive. However, affordable prints are available. Moreover one need not be ashamed of hanging a reproduction on a wall in one’s home.

Katsushika Hokusai

In this post, I will simply discuss beauty: its relativity and mankind’s ability to see beauty in the unfamiliar. However, I will not do so in any depth.

At the top of our post, is a very famous print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa. It is the first in a series of thirty-six prints constituting Katsushika Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (1823-1829). One may see all thirty-six views by clicking on the title of the series: Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.

Umegawa in Sagami Province,The Kazusa Province sea route (Photo credit: Wikipedia) (Please click on the images to enlarge them.)

Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji

Not only did Hokusai make a series of thirty-six prints depicting various views of Mount Fuji, but he went on to make a hundred: One-hundred Views of Mount Fuji (1834). Hokusai demonstrated that depending on the direction from which Mount Fuji was drawn, not to mention the weather and the season, depictions of its reality varied. To the Impressionists, this was grist to the mill as they were fascinated by the manner in which light kept reshaping reality.

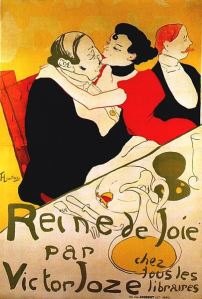

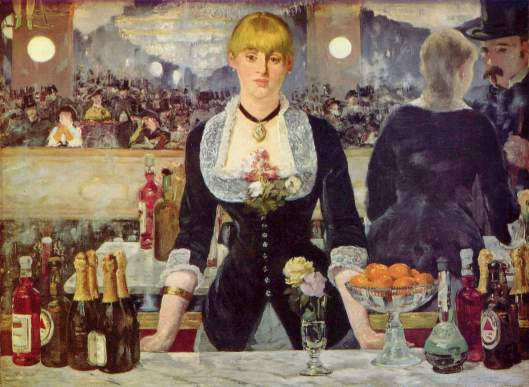

The more important factor, however, was the popularity of an art that differed from Western art. As soon as they reached Europe, the Japanese prints were considered beautiful by artists such as Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas and, later, Vincent van Gogh. Claude Monet purchased as many prints as he could. This degree of enthusiasm attested to the fact that, even otherwise expressed, “reality” could be beautiful and that it could be beautiful to several individuals.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa

Given the popularity of The Great Wave off Kanagawa, one could presume that beauty is an absolute. This cannot be the case, at least not altogether. What Europeans saw as beautiful was not the beauty their academicists rewarded, but an exotic form of beauty and, in the case of Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, the beauty of one print in particular: The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

The popularity of The Great Wave showed not only that many individuals could agree on what was and was not beautiful, but that many individuals could also agree that art rooted in an oriental form of aesthetics was beautiful. However, despite a consensus regarding the beauty of The Great Wave off Kanagawa, I doubt very much that its popularity suggested that beauty was an absolute.

Quotations

Allow me to quote one of my former professors who writes that, in 1874, a group of painters working in Paris formed a “loose association” and put on an exhibition under the title of “The Anonymous Society of Painters and Sculptors.” Critics were in attendance:

“To describe what they saw there, critics coined a new word—Impressionism. It was no compliment, however. As one of them put it: We have seen an exhibition by the Impressionalists . . . M. Manet is among those who maintain that in painting one can and ought to be satisfied with the impression. . . .[They] appear to have declared war on beauty.”[i]

Émile Zola spoke for the Impressionists when he declared flatly that,

“. . . Beauty is no longer an absolute, a preposterous universal standard. Beauty is identical with itself. . . . Beauty lives within us, not outside us. What do I care for philosophical abstraction, for an ideal perfection conjured up by a small group of men! What interests me as a man is mankind, the source of my life.”[ii]

Woman looking in Mirror (Artinthepicture.com) Woman (hellaheaven-ana.blogsp) Woman profile (Wikipaintings)Conclusion

One particularly “avid” collector of Japanese prints was Frank Lloyd Wright. In fact, Wright also sold ukiyo-e woodblock prints. (See Frank Lloyd Wright, Wikipedia.)

However, I will close this post by quoting Van Gogh. (See Japonaiserie [Van Gogh], Wikipedia.)

“In a letter to Theo dated about 5 June 1888 Vincent remarks

- About staying in the south, even if it’s more expensive — Look, we love Japanese painting, we’ve experienced its influence — all the Impressionists have that in common — [so why not go to Japan], in other words, to what is the equivalent of Japan, the south? So I believe that the future of the new art still lies in the south after all.”

Related articles

- Great Waves: Inspired by Hokusai (June 2013) (hannahsartclub.wordpress.com)

- Utamaro’s Women & Japonisme (michelinewalker.com)