Tags

archetype, Boasting, Cycles and Motifs, Dom Juan, Grenouille et Boeuf, La Fontaine, Molière, The Frog and the Ox

John Ray [EBook #24108]

La Fontaine: site officiel

A few days ago, I attempted to write a short post on Jean de La Fontaine‘s La Grenouille qui se veut faire aussi grosse que le bœuf (The Frog Who Wished To Be As Big As The Ox). Although the genre and length differ, in both cases, boasting leads to devastating consequences. La Fontaine’s Site officiel no longer provides the text, in French and in English, of La Fontaine’s twelve books of fables. The new site may still be under construction, but it will be mostly for visitors to the Musée. At any rate, I decided to use les moyens du bord, sites such as Project Gutenberg, Internet Archive, Wikisource, and other sources. I will update all my posts featuring a fable by La Fontaine.

La Fontaine’s La Grenouille qui se veut faire aussi grosse que le bœuf is one of Æsop’s Fables. It is number 376 in the Perry Index. Now, The Frog and Ox is, in its broadest terms, a fable version of Dom Juan. Fables often have a farcical ending. They tell us to think of the consequences, but wrap the truth in a lie: animals do not speak, yet they do. Animals speak, yet they don’t.

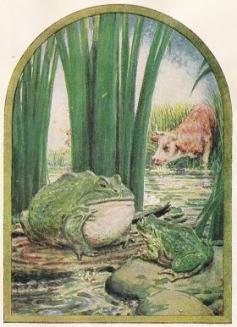

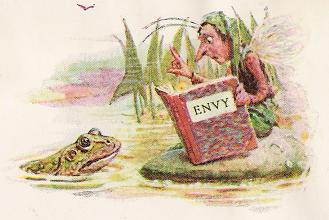

Wikipedia’s entries on La Fontaine’s fables often contain not only a translation, but also images. Gutenberg’s [EBook #24108] was illustrated by John Rae. The fables were translated by W. T. (William Trowbridge) Larned. It is an edition for children and it is beautiful!

John Ray [EBook #24108]

John Ray [EBook #24108]

The Frog and the Ox

A Frog had an Ox in her view;

His bulk, to her, appeared ideal.

She, not even as large, all in all, as an egg hitherto,

Envious, stretched, swelled, strained, in her zeal

To match the beast in overall size,

Saying, “Sister, lend me your eyes.

Is this enough? Am I not yet there, in every feature?”

“Nope.” “Then now?” “No way.” “There now, as good as first?”

“You’re not anywhere near.” The diminutive creature

Inflated still more, till she burst.

The world is full of folk who are as far from being sages.

Every city gent would build chateaux like Louis Quatorze;

Every petty prince names ambassadors,

Every marquis wants to have pages.

credit

http://lafontaine.mmlc.northwestern.edu/fables/grenouille_boeuf_en.html

La Grenouille qui se veut faire aussi grosse que le bœuf

Une Grenouille vit un Bœuf

Qui lui sembla de belle taille.

Elle qui n’était pas grosse en tout comme un œuf,

Envieuse s’étend, et s’enfle, et se travaille

Pour égaler l’animal en grosseur,

Disant : « Regardez bien, ma sœur,

Est-ce assez ? dites-moi : n’y suis-je point encore ?

— Nenni. — M’y voici donc ? — Point du tout. — M’y voilà ?

— Vous n’en approchez point. » La chétive pécore

S’enfla si bien qu’elle creva.

Le monde est plein de gens qui ne sont pas plus sages :

Tout Bourgeois veut bâtir comme les grands Seigneurs,

Tout petit Prince a des Ambassadeurs,

Tout Marquis veut avoir des Pages.

credit: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Grenouille_qui_se_veut_faire_aussi_grosse_que_le_b%C5%93uf

La Fontaine, Molière, etc.

La Fontaine and Molière were contemporaries and friends, close friends, it would seem. La Fontaine was a pallbearer when Molière was buried under cover of darkness. Comedians were excommunicated. La Grange (Charles Varlet, sieur de la Grange) kept the books, le registre. We know, therefore, what fabric was used to make certain costumes, but we do not know why Jean-Baptiste Poquelin chose the name Molière. There are so many names. Molière did not say much about himself, nor did La Fontaine.

However, Dom Juan boasts, as does La Fontaine’s frog. No frog can be as large as an ox. It therefore bursts as do the bombastic characters of the commedia dell’arte and those of Greek and Latin comedy. The alazṓn of ancient Greece could be a senex iratus, an angry old man, or a miles gloriosus, a boastful character. Dom Juan is a miles gloriosus, un fanfaron.

Molière also depicted his century in a natural fashion, using correct but ordinary French. French is called “la langue de Molière.” As well, Alceste (The Misanthrope) is an atrabilaire amoureux. There were four temperaments or humeurs. When discussing medicine and Molière, I mentioned the four temperaments or humeurs. Philinte is flegmatique. As for Dom Juan, who is “jeune encore” (still young), I believe he would be a sanguine temperament. These words are still used. I was told about the four “temperaments” as a child.

The Four Temperaments (Psychologia.co)

Moreover, these characters, including our boastful frog, are archetypes. The miles gloriosus is an archetype. We associate archetypes with Jungian psychology, but the stock characters of the commedia dell’arte are also archetypes, as is Æsop/La Fontaine’s boastful frog. Literature has its genres, archetypes, themes, motifs, cycles, etc.

However, until André Villiers, Molière was seldom looked upon as a philosopher, or philosophe (thinker). The philosophes of the French Enlightenment discussed individual rights versus collective rights and other subjects. This discourse, freedom mostly, begins in ancient Greece, if not earlier. Montaigne takes it up. It crosses the seventeenth century in France and elsewhere. It includes le libertinage érudit (Dom Juan). It finds an apex in John Locke (see the Age of Enlightenment), and is finely articulated in the writings of the philosophes of the French Enlightenment, such as Montesquieu and Voltaire, who met in the Salons. Rousseau‘s Le Contrat social was published in 1762. Freedom demands that certain freedoms be denied and some restored or instituted.

Dom Juan XII par Claude Weisbuch, circa 1990 (Galerie 125)

Conclusion

It is unlikely that in “Elfland”[1] a husband can abandon his wife. There may not be husbands and wives in Elfland. A small, but boastful frog is not a Dom Juan defying God, the devil according to some critics.[2] However, fables are anthropomorphic. So, boastful frogs are used to depict boastful human beings. Both our frog and Dom Juan pit themselves against the impossible, including Heaven … and burst. Bursting is a motif.

Our next play is Les Fourberies de Scapin (Scapin the Schemer). Scapin is the most ingenuous zanni before Figaro.

____________________

[1] G. K. Chesterton, “The Ethics of Elfland,” Orthodoxy (New York: Dood, Mead and Company, 1943 [1908]), pp. 81-118.

[2] Claude Reichler, La Diabolie: la séduction, la renardie, l’écriture (Paris : Éditions de Minuit, 1979), p. 17.

P. S. Please see David Nicholson’s comment, below. The remains, or what are believed to be the remains, of La Fontaine and Molière are side by side in the Père Lachaise cemetery

Love to everyone 💕

Hank Knox – Rameau, La Poule

Le Musée du Château Dufresne, Montréal, QC

Crispin et Scapin peinture d’Honoré Daumier, XIXe siècle.

© Micheline Walker

23 August 2019

WordPress