Tags

Aesthete Movement, Anglo-Japanese style, Art for Art's Sake, Cabinet-making, Japonism, John Ruskin, Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, The Decorative Arts, The Gothic, William Morris

Boreas by John Willam Waterhouse, 1903 (Photo credit: WikiArt.org )

Prelude

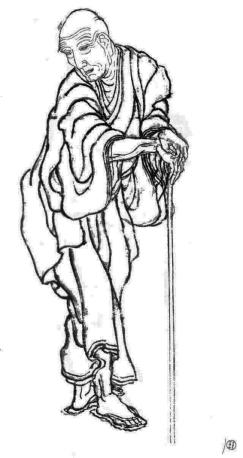

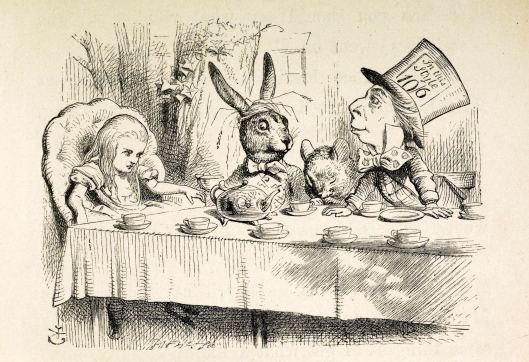

Britain’s Golden Age of illustration, the illustration of children’s literature in particular, was ushered in, at least in part, by Japonism. Other factors contributed to the flourishing of children’s literature adorned with exquisite illustrations, but the beauty of the Japanese prints that flooded Europe after the Sakoku period elevated the status of illustrators whose art was engraved and printed. Moreover, the illustration of children’s literature allowed and sometimes required substantial creativity on the part of illustrators. For instance, as discussed in a previous post, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass (1871), featured literary nonsense.

But there is more to tell. We will now introduce Britain’s following movements or style:

- the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (1848)

- the Arts and Crafts Movement (1880-1910)

- the Anglo-Japanese style (c. 1850)

- the Aesthetic Movement (c. 1850)

I will also refer to the curvilinear and very popular and influential Art Nouveau. British illustrator Aubrey Beardsley (21 August 1872 – 16 March 1898; aged 25) is a representative of the style, but Art Nouveau is usually associated with Czech artist Alfons Mucha. It is a characteristic of art produced in the last decade of the 19th century and in the years preceding World War I.

The Anglo-Japanese Style

In Britain, Japonisme was applied to furniture making and was referred to as the Anglo-Japanese style. The Anglo-Japanese style was true to the idealism of the Pre-Raphaelites in that it rejected the depiction of “any thing [sic] or any person of a commonplace or conventional kind.” (See Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Wikipedia.)

For instance, the sideboard shown below, designed in the Anglo-Japanese style by Arthur William Godwin (26 May 1833 – 6 October 1886), cannot be considered “conventional”. It may reflect Japanese furniture, but it is also consistent with the concept of art for art’s sake, l’art pour l’art, advocated by French poet Théophile Gautier (30 August 1811 – 23 October 1872) and shared by certain members of the Aesthetic Movement, such as James Abbott McNeil Whistler. Yet, as noted above, the Anglo-Japanese style is partly rooted in the creed of members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. It is innovative, Charles Baudelaire‘s “du nouveau,” newness.

Plonger au fond du gouffre, Enfer ou Ciel, qu’importe?

Au fond de l’Inconnu pour trouver du nouveau!

(See “Le Voyage” VIII, Les Fleurs du mal [The Flowers of Evil].)

Sideboard by Arthur William Godwin (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in 1848 by British artists William Hunt (2 April 1827 – 7 September 1910), John Everett Millais (8 June 1829 – 13 August 1896) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882). As noted below (see 3), it would not allow any thing [sic] or person “of a commonplace or conventional kind.”

- The movement was called brotherhood, which could suggest equality and fraternity, but members of the brotherhood were brothers in that they rejected Sir Joshua Reynolds, (16 July 1723 -23 February 1792), renamed Sir ‘Sloshua’, the founder of the English Royal Academy of Arts.

- Pre-Raphaelites also wished to return to the art preceding the High Renaissance paintings of Raphael (6 April or 28 March 1483 – 6 April 1520).

- Pre-Raphaelites would not allow “anything lax or scamped in the process of painting … and hence … any thing [sic] or person of a commonplace or conventional kind.”[1] (See Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Wikipedia.)

- But the group “continued to accept the concepts of history painting, mimesis, imitation of nature as central to the purpose of art.” (See Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Wikipedia.)

- The Pre-Raphaelites’ mentor was John Ruskin (8 February 1819 – 20 January 1900), the most prominent art critic of the Victorian era who advocated “truth to nature.”

- It would be joined by other artists.[2]

(See Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Wikipedia.)

Echo and Narcissus by John William Waterhouse, 1903 (Photo credit: WikiArt.org)

The Aesthetic Movement

- roots in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

- roots in the Gothic (William Morris & Edward Burne-Jones)

- roots in Japonism (Impressionism)

The Aesthetic Movement promoted the concept of art for art’s sake, l’art pour l’art. Consequently, there are affinities between the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Aesthetic Movement. They may differ however in that the Pre-Raphaelites “continued to accept the concepts of history painting, mimesis, imitation of nature as central to the purpose of art.” This could explain why John Ruskin (8 February 1819 – 20 January 1900) praised the movement (see 5). He advocated “truth to nature”.

For Ruskin “truth to nature” did not seem consistent with the allusive nature of McNeill’s Impressionism. John Ruskin therefore criticized American, but London-based artist James McNeill Whistler stating that Whistler was a “coxcomb” who “asked two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” (See James Abbott McNeil Whistler, Wikipedia.) Such was John Ruskin’s description of Whistler’s “Nocture in Black and Gold, the Falling Rocket”. Whistler sued and won, but he had to declare bankruptcy and lost the “White House” designed for him by Arthur William Godwin, the cabinet-maker who created the “sideboard” shown above.

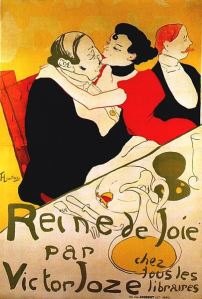

Yet if the Pre-Raphaelites are to be linked to another 19th-century British art movement, it would be the art for art’s sake Aesthetic Movement which paralleled, albeit to a lesser extent, the decadence of French poets and artists of the second half of 19th-century. French poets were drinking absinthe, which contained an hallucinogen, thujone. For his part, Dante Gabriel Rossetti took chloral.

Although James McNeill Whistler introduced Dante Gabriel Rossetti to Japonism in 1860, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood is not related to Japonism. It remains however that if the Aesthetic movement could accommodate “Ruskinian Gothic,” not to mention the medievalism of such devotees as William Morris and Sir Edward Burne-Jones, one wonders why it would reject Ruskinian “truth to nature”.

The Gothic

- William Morris

- Edward Burne-Jones

Arthur William Godwin‘s “sideboard” is in the Anglo-Japanese style, which, as is the case with all the movements listed above, is a forerunner of Aestheticism. As an architect-designer, Godwin, who designed the desk displayed above, also drew his inspiration from “Ruskinian Gothic”. Although exotic Japonism helped shape the art of 19th-century Britain, the stained-glass pieces of Sir Edward Burne-Jones (28 August 1833 – 17 June 1898) reached into the Medieval era, as did Arthur William Godwin’s gothic Northampton Guildhall. Morris and Burne-Jones met as students at Oxford and both were attracted to the Middle Ages, or Gothic, praised by John Ruskin (8 February 1819 – 20 January 1900) who was not only the most prominent art historian and critic of the Victorian era, but also a fine artist.

Northampton Guildhall, built 1861-64, displays Godwin’s “Ruskinian Gothic” Style (Photo credit: Flicker)

John Ruskin: The Stones of Venice

John Ruskin is the author of the Stones of Venice, published in three volumes between 1851 and 1853. William Morris was so impressed by a chapter entitled “On the Nature of the Gothic”, that he had it printed separately by Kelmscott Press, the Arts and Crafts press, named after Kelmscott Manor, the Morris family’s country residence. (See Morris and the Kelmscott Press, the Victorian Web.) In 1861, William Morris founded a firm, the Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. (See Peter Paul Marschall and Charles Joseph Faulkner, Wikipedia.)

The Peacock room, The Princess from the Land of Porcelain by William McNeill Whistler (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

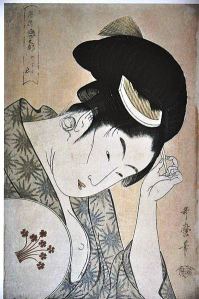

Japonism and the Aesthetic Movement

Whistler was one of the first to appreciate the true significance of the Japanese prints which had begun to appear in the West after Japan’s centuries of isolation ended in the 1850s, and to see that such works, whose subject matter was generally unknown or without much meaning even when it was ascertainable, forced people to think and to see entirely in terms of pictorial qualities, of line and pattern and color; to adapt them as demonstrations of the principle that Reality in painting is intrinsic, not a matter of copying anything outside itself.[3]

Japonism, however, would characterize the art of American but London-based James McNeill Whistler and American impressionist William Merritt Chase (1 November 1849 – 25 October 1916). Their Japonism is one of subject matter mainly, but exotic subject matter depicted in the rather allusive manner of Impressionism. Both showed blue and white porcelain, fans, screens and ladies wearing kimonos that displayed an oriental motif. “The Blue Kimono,” featured below, is one of the finest paintings created by William Merritt Chase.

The Blue Kimono by William Merritt Chase, 1898 (Photo credit: WikiArt.org)

Cult of Beauty or Symphony in White no 2 (The Little White Girl) by James McNeill Whistler (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Whistler and Chase: the Decorative Arts

- rooms copied

- studios copied

Ironically, it could be said of both Whistler and Chase that their Japonism was of a decorative nature. The rooms they showed became fashionable and so did the clothes worn by the ladies they portrayed. Whistler’s “Peacock Room” is not altogether consistent with the domestication of the arts advocated by the Arts and Crafts Movement, founded by William Morris. Whistler’s “Peacock Room” is a room, but it borders on art for art’s sake. It was designed in the Anglo-Japanese style and is housed in the Freer Gallery of Art, in Washington D.C..

The Tenth Street Studio by William Merritt Chase (Photo credit: WikiArt.org)

Conclusion

- the broadening of the arts

- the versatility of artists

Anglo-Japanese Style was applied to cabinet-making. However, the 19th-century British art movement we tend to associate with interior design and the decorative arts is the Arts and Crafts Movement, founded by William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896). The Arts and Crafts Movement will be discussed in a separate post, but we have already witnessed a certain domestication of the art and a broadening of the field of art. Henceforth, it will include applied arts and such artists as William Morris and Sir Edward Burne-Jones will be extremely versatile. Whistler, who designed the luxurious “Peacock Room” and sued revered Ruskin, was an interior designer, a painter, and a printmaker.

RELATED ARTICLES

- William Merritt Chase: Japonisme in America (6 July 2013)

- James McNeil Whistler: a Subtler Art (24 April 2013)

Sources and Resources

- The Victorian Web, Kelmscott Press

http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/morris/kelmscott.html - John Ruskin

The Stones of Venice is an Internet Archive Publication (Vol. I)

The Stones of Venice is an Internet Archive Publication (Vol. II)

The Stones of Venice is an Internet Archive Publication (Vol. III)

____________________

[1] Timothy Hilton, The Pre-Raphaelites (Oxford University Press, 1970), p. 46.

[2] They would be joined by painters James Collinson and Frederic George Stephens, Rossetti’s brother, poet and critic William Michael Rossetti, and sculptor Thomas Woolner, Sir Edward Burne-Jones, and John William Waterhouse.

[3] Alan Gowans, The Restless Art: a History of Painters and Painting 1760-1960 (Philadelphia and New York: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1966), p. 237.

Nathan Milstein plays Jules Massenet’s Méditation from Thaïs

© Micheline Walker

19 November 2015

WordPress