Tags

Bidpai, D. L. Ashliman, Horace, Jean de La Fontaine, Le Livre des lumières, metamorphosis, metempsychosis, Nature will out, The Panchatantra, The Soul of Animals

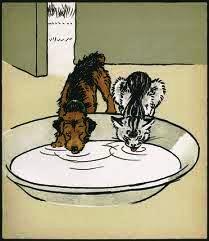

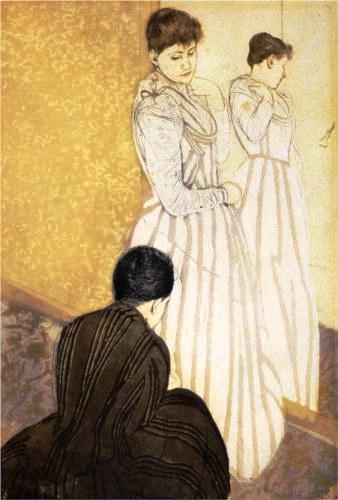

The Cat Metamorphosed into a Woman, by Arthur Rackham

(Photo credit: The Project Gutenberg [EBook #11339])

Aarne-Thompson (Aarne-Thomson-Uther) type 2031C.

Aesop’s Fables: Venus and the Cat (The Project Gutenberg [EBook #11339])

Fables d’Ésope: La Chatte et Aphrodite

La Fontaine: La Chatte métamorphosée en femme (II.18)

La Fontaine: The Cat Metamorphosed into a Woman (II.18)

La Fontaine: La Souris métamorphosée en fille (IX.7)

La Fontaine: The Mouse Metamorphosed into a Maid (IX.7)

The Cat Metamorphosed into a Woman, by Arthur Rackham

(Photo credit: The Project Gutenberg [EBook #11339])

Aarne-Thompson (Aarne-Thomson-Uther) type 2031C.

Aesop’s Fables: Venus and the Cat (The Project Gutenberg [EBook #11339])

Fables d’Ésope: La Chatte et Aphrodite

La Fontaine: La Chatte métamorphosée en femme (II.18)

La Fontaine: The Cat Metamorphosed into a Woman (II.18)

La Fontaine: La Souris métamorphosée en fille (IX.7)

La Fontaine: The Mouse Metamorphosed into a Maid (IX.7)

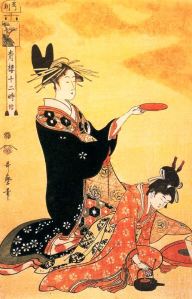

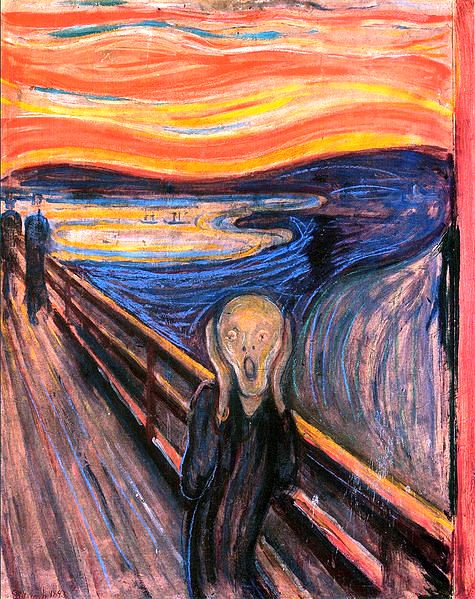

La Souris métamorphosée en fille

La Fontaine’s First Collection of Fables (1668)

Jean de La Fontaine‘s Cat Metamorphosed into a Woman (II.18) belongs to the second of six books of fables he published in 1668. As we have seen, it is a Aesopic fable. However, La Fontaine’s immediate source was Névelet’s 1610 Latin edition of Aesop’s Fables, the Mythologia Æsopica Isaaci Nicolai Neveleti (Frankfurt, 1610) where the same fable, by Aesop, is entitled Venus and the Cat. The moral of The Cat Metamorphosed into a Woman is Horatian:

The Delights of Nature (Horace, Epistles, Book I. x, lines 1-25) Drive Nature off with a pitchfork, she’ll still press back, And secretly burst in triumph through your sad disdain. (lines 24-25) or Limit your desires (Horace, Epistles, Book I, ii, lines 55-71) A jar will long retain the odor of what it was Dipped in when new. (lines 69-70)La Fontaine’s Second Collection of Fables (1678)

In Book IX:vii of his second volume of fables (1678), Jean de La Fontaine published La Souris métamorphosée en fille (The Mouse Metamorphosed into a Maid). The Mouse Metamorphosed into a Maid is not rooted in the Aesopic corpus, but finds its origin in the Panchatantra (3rd century BCE, or earlier), where it is entitled The Mouse Turned into a Maid or The Transformed Mouse Seeks a Bridegroom.

ne, he drew his fable[i] from Le Livre des lumières ou la conduite des roys (The Book of Enlightenment or the Conduct of Kings), published in 1644 by Gilbert Gaulmin (1585-1665) who used a pseudonym. He called himself David Sahid d’Ispahan. Le Livre des lumières ou la conduite des roys contains fables by storyteller Bidpai or Pilpay (FR), the storyteller featured in both the Sanskrit Panchatantra, by Vishnu Sharma, and its Arabic version, Kalīlah wa-Dimnah, written by Persian scholar Ibn Al-Muqaffa’. The Panchatantra was well-known and it migrated to both Eastern and Western countries. According to Edgerton (1924), who translated the Panchatantra into English,

…there are recorded over two hundred different versions known to exist in more than fifty languages, and three-fourths of these languages are extra-Indian. As early as the eleventh century this work reached Europe, and before 1600 it existed in Greek, Latin, Spanish, Italian, German, English, Old Slavonic, Czech, and perhaps other Slavonic languages. Its range has extended from Java to Iceland… [In India,] it has been worked over and over again, expanded, abstracted, turned into verse, retold in prose, translated into medieval and modern vernaculars, and retranslated into Sanskrit. And most of the stories contained in it have “gone down” into the folklore of the story-loving Hindus, whence they reappear in the collections of oral tales gathered by modern students of folk-stories. (See Panchatantra, Wikipedia.)Although both The Cat Metamorphosed into a Woman (II.xviii) and The Mouse Metamorphosed into a Maid feature a metamorphosis gone awry. Yet, not only are their source different, but so are their narratives. La Fontaine’s La Souris métamorphosée en fille (The Mouse Metamorphosed into a Maid) is a rather long fable. One may read it in full by clicking on the title on the fable. However, I will provide a summary.

A mouse falls from an owl’s mouth. The storyteller does not pick her up, but a Brahmin does and this Brahmin knows a sorcerer. The sorcerer transforms our mouse into a Maid. She grows up as a maid, but when she turns fifteen and time has come for her to marry, the Brahmin seeks a husband for her. Suddenly problems arise. The girl wants a powerful husband but she is rejected by the son of Priam, the Sun, a Cloud, the Wind, and a Mountain. However, our lovely maid is not disappointed because she herself is not interested in the suitors who have rejected her. She finally expresses a degree of satisfaction when she hears the word “rat.” The rat rejects her as do a cat, a dog, a wolf… The sorcerer reappears, nearly fifteen years later, and states that one chooses a mate among one’s kind and one’s kind share the same soul. Consequently, metempsychosis, the migration of a soul, is not possible. In other words, as is the case in The Cat Metamorphosed into a Woman, although the mouse has grown into a beautiful girl, her human form is skin-deep. She has the soul of a mouse, not that of a human being.La Fontaine does not tell us what happens to the mouse metamorphosed into a maid (she is turned back into a mouse), but here is his moral:

In all respects, compared and weighed, The souls of men and souls of mice Quite different are made, Unlike in sort as well as size. Each fits and fills its destined part As Heaven does well provide; Nor witch, nor fiend, nor magic art, Can set their laws aside. La Fontaine (IX.vii) Parlez au diable, employez la magie, Vous ne détournerez nul être de sa fin [destined part]. La Fontaine (IX.vii)As mentioned above, The Mouse Metamorphosed into a Maid is rooted in the Panchatantra and its Arabic version, Kalīlah wa-Dimnah. It has the same moral as The Cat Metamorphosed into a Woman: “Nature will out.” But its narrative differs, to a greater than lesser extent, from that of The Cat Metamorphosed into a Woman (II.xviii). Finally, both are listed as Aarne-Thompson type 2031C. However, Professor D. L. Ashliman does not include La Fontaine’s two fables in his list of “cumulative tales.”

Aarne-Thompson or Aarne-Thompson-Uther types 2000-2100 are all cumulative or chain tales. As indicated above, when writing The Mouse Metamorphosed into a Maid, La Fontaine drew his material from the Sanskrit The Mouse Turned into a Maid or The Transformed Mouse Seeks a Bridegroom, which is a cumulative tale and is listed under: Chains Involving Other Events 2029-2075. According to D. L. Ashliman, The Mouse Turned into a Maid or The Transformed Mouse Seeks a Bridegroom (The Panchatantra, India) shares affinities with the following stories or narratives:[ii]

The Husband of the Rat’s Daughter or The Rats and Their Daughter (Japan) A Bridegroom for Miss Mole (Korea) The Story of the Rat and Her Journey to God (Romania) The Most Powerful Husband in the World (France and French North Africa)Conclusion

Reason vs Instinct

La Fontaine’s moral is very clever. He does not deny that animals have a soul, but he states clearly that animals have a soul, but that it is a soul of their own.

The souls of men and souls of mice Quite different are made[.]The Primacy of Reason challenged

The primacy of reason was challenged almost as soon as René Descartes published his Discourse on Method (Discours de la méthode) in 1637.[iii] According to Descartes, animals function much as clocks do. They were looked upon as machines. But, Blaise Pascal (19 June 1623 – 19 August 1662) argued that humans are endowed with both reason and instincts: Le coeur a ses raisons que la raison ne connaît point. (Les Pensées, published posthumously). Instincts are a characteristic humans share with animals, yet it was Pascal’s conviction that reason needed the support of instincts or le coeur, the heart: c’est sur ces connaissances du coeur et de l’instinct qu’il faut que la raison s’appuie (reason must lean on knowledge gleaned from the heart and instinct). See Pierre Magnard. In my opinion, such was also La Fontaine’s view. I have written a post on this subject: The Two Rats, Fox and Egg: The Soul of Animals.

So two little fables about a cat and a mouse transformed into a woman or girl contain the wisdom of their century as does The Two Rats, Fox and Egg: The Soul of Animals. Moreover, both the The Cat Metamorphosed into a Woman and The Mouse Metamorphosed into a Maid deny metempsychosis by featuring an attempted and partly successful metamorphism or metempsychosis.

From Mouse to Mouse

Ironically, the sorcerer is the character who says that sorcery does not work fully, which is contrary to his transforming the mouse into a maid. The structure of this fable therefore resembles that of The Cat Metamorphosed into a Woman (II.xviii) and Venus and the Cat. So the moral of La Fontaine’s The Mouse Metamorphosed into a Maid is expressed not only in words, but through form.

The very thing the wizard did Its falsity exposes If that indeed were ever hid.In other words, the story or narrative could be summed up in a short phrase. It is “from mouse to mouse” as it is “from ashes to ashes.” As powerful as he was, Louis XIV could no more escape death than the humblest of his nation’s impoverished peasants: memento mori.

______________________________ [i] He acknowledged he did, see Bidpai (Wikipedia). [ii] Different folktales may have the same title and the same folktale may have different tiles. Moreover, a folktale (fables, fairy tales, etc.) may belong to more than one AT type. Finally, various animals can play the same role. That role is then called a function. [iii] The Discours de la méthode (1637) is The Project Gutenberg’s [EBook #13846]. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791) Variations in C Major on the French Song “Ah! vous dirai-je, Maman,” K. 265 Walter Klien, piano Gerbil, by

Jacopo Ligozzi (1547–1627)

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

© Micheline Walker

July 29, 2013

WordPress

Gerbil, by

Jacopo Ligozzi (1547–1627)

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

© Micheline Walker

July 29, 2013

WordPress