Tags

Communards, Commune de Paris, Franco-Prussian War, La Semaine sanglante, Le Temps des cerises, Nineteenth-Century France, Paris Commune, The Third Republic

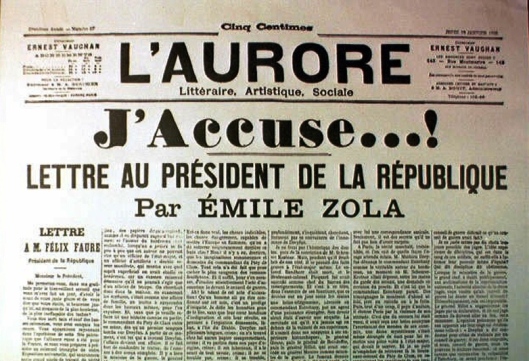

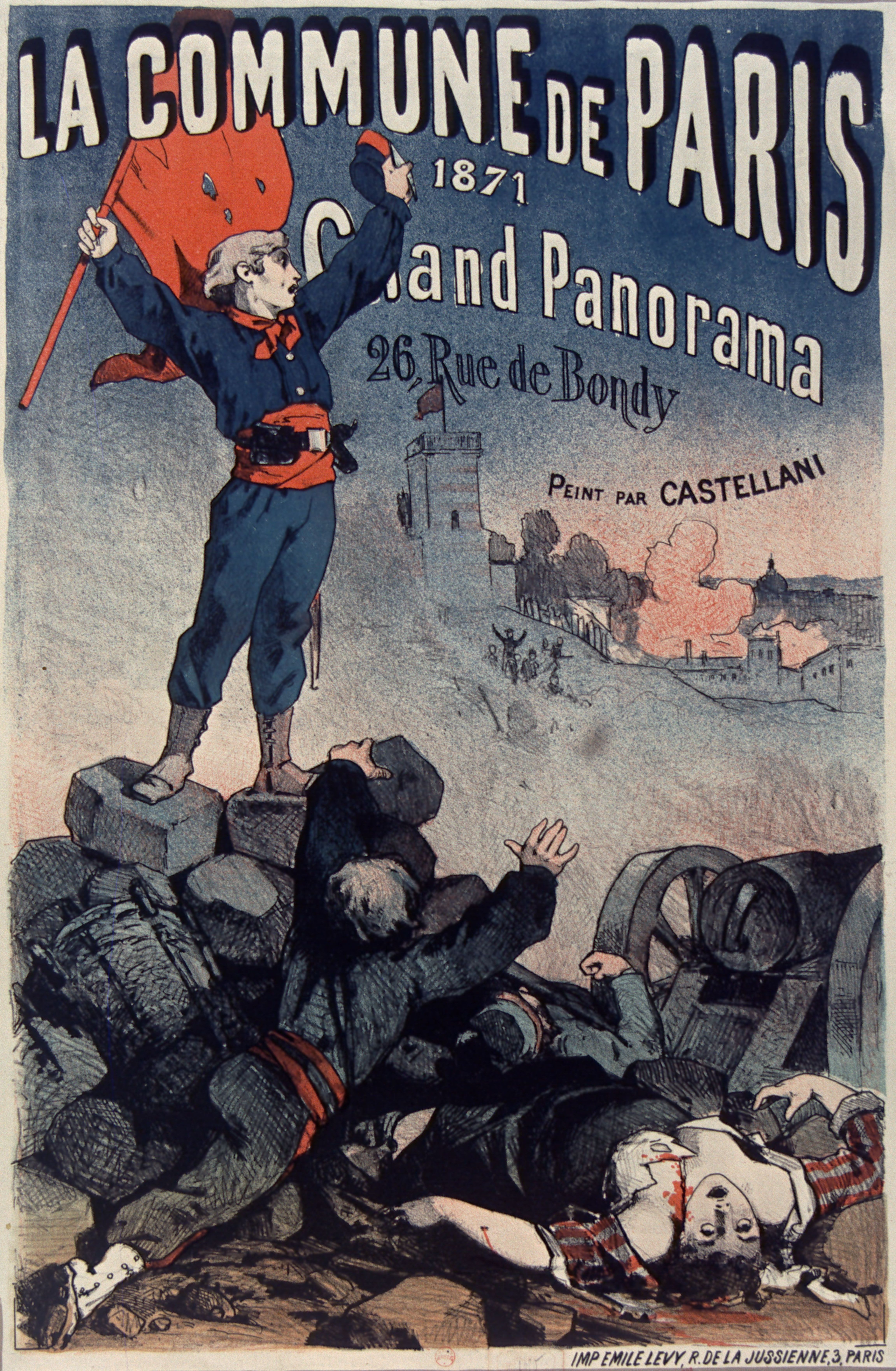

A few years ago, I posted an article on the 19th century in Franch. The post did not include a discussion of the Franco-Prussian War and the Third Republic, which was in fact a first Republic. This post is not a discussion of the entire thirty years of the 19th century in France, but it sheds light on the Franco-Prussian War (1870), the Paris Commune in particular and therefore Le Temps des cerises.

Le Temps des cerises is dedicated to The Paris Commune of 1871, and more precisely to one ambulancière. The Communards were eliminated, but it was a golden age one mourned. In À la claire fontaine, a love song, French-speaking Canadians mourn France. It is a metamorphosis. France is a woman.

The Unification of Germany

- the nineteenth century: monarchs and emperors

- three Republics: 1792, 1848, 1871

In the earlier part of the 19th century, Germany consisted in several German-language states. These were unified under Otto von Bismarck. Bismarck failed to bring Austria under the fold, but he was otherwise successful. Italy was also unified in the 19th under the leadership of Giuseppe Garibaldi.

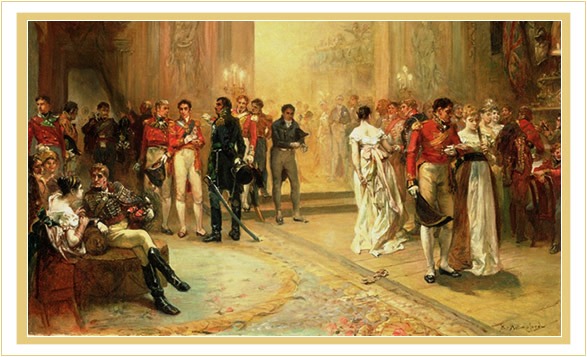

In the above-mentioned post, entitled The Nineteenth-Century in France, I described two Empires and two Monarchies (three kings). The post showed that the Monarchy in France did not end on 21 January 1793, the day Louis XVI was guillotined. His son, Louis XVII, died in captivity in 1795 at the age of 10. He was at best a titular King. After Louis XVI’s execution, the Republic was ruled by the National Convention, a revolutionary government. France was again a republic in 1848, though shortly. Its duly-elected President was Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte who proclaimed himself Emperor of the French. (See 1851 French coup d’état, Wiki2.org.)

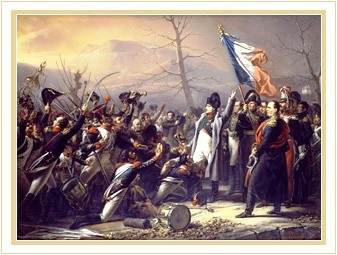

Napoleon III declared war on Prussia in July 1870, but France was defeated at the Battle of Sedan and Napoleon III was captured. After his release, he went to England where he died on 9 January 1873. It is as though France had finally become a genuine Republic, but it had lost and grieved Alsace-Lorraine and had to pay penalties.

The Third Republic

- The Paris Commune, a vanishing dream

- a lingering Monarchy

The Third French Republic would last until 1940, when France fell to Nazi Germany. The first president of the Third Republic was Adolphe Thiers who, to a certain extent, was a figurehead. The French envisioned a monarchy until 1880. So, the monarchy lingered.

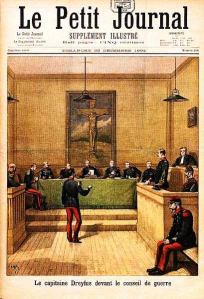

Moreover, the Third Republic had its government in Tours, the Communards ruled Paris. They had ruled Paris since 18 March 1971. The Paris commune was a government by radical socialists and revolutionaries. (See The Paris Commune, Wiki2.org.) The new Republic sent the National Guard to Paris to quell the communards. Several members of the National Guard joined the communards. So did a young woman, an ambulancière (a nurse) who was killed. Louise Michel wrote about her in La Commune Histoire et Souvenirs (1898). (See Le Temps des cerises, footnote I, Wiki.org)

Au moment où vont partir leurs derniers coups, une jeune fille venant de la barricade de la rue Saint-Maur arrive, leur offrant ses services : ils voulaient l’éloigner de cet endroit de mort, elle resta malgré eux. Quelques instants après, la barricade jetant en une formidable explosion tout ce qui lui restait de mitraille mourut dans cette décharge énorme, que nous entendîmes de Satory, ceux qui étaient prisonniers ; à l’ambulancière de la dernière barricade et de la dernière heure, J.-B. Clément dédia longtemps après la chanson des cerises. Personne ne la revit.[…] La Commune était morte, ensevelissant avec elle des milliers de héros inconnus.

As they were about to fire their last shots, a young woman [une ambulancière/ a nurse], coming from the barricade of Saint-Maur street, arrived, offering her services: they could not send her away from this place of death, she stayed despite their entreaties. A few moments later, the barricade exploded and all that remained of its ammunition died. From Satory [near Versailles], we heard those who had been taken prisoners [say]; from the nurse of the last barricade and of the last hour (…). No one saw her again. The Commune had died burying thousands of unknown heroes.

Below is the song of the communards, composed by Jean Baptiste Clément.

Literary works are associated with the Franco-Prussian War. Particularly famous are:

- La Dernière classe, by Alphonse Daudet (a short story) in Les Contes du lundi

- Le Dormeur du Val, by Arthur Rimbaud (a poem) FR

- Victor Hugo‘s writings. He fled to Jersey, a channel island.

RELATED ARTICLES

- The King’s Swiss Guard (14 September 2018)

- The Nineteenth Century in France (28 July 2018)

Sources and Resources

Alphonse Daudet’s Les Contes du lundi is a Wikisource publication FR

See page, The French Revolution and Napoleon Bonaparte

—ooo—

Love to everyone 💕

We now return to the Pandemic in Canada, its epicentre remaining Montreal.

Texte 1871 de Jean-Baptiste Clément

Interprétation 1969 Marc OGERET

La Commune de Paris / La Semaine sanglante

Le Temps des cerises, Hervé David, accompagné au piano par Benjamin Intartaglia.

© Micheline Walker

24 May 2020

WordPress