Tags

Dreyfus Affair, Edgar Degas, Impressionism, landscapes, pastels, Realism, Social Realism, Valery-sur-Somme

Beach with Sailing Boats, 1869 (pastel)

Beach at Ebbe, 1870 (pastel)

(Please click on the smaller images to enlarge them.)

Beach with Sailing Boats, 1869 (pastel)

Beach at Ebbe, 1870 (pastel)

(Please click on the smaller images to enlarge them.)

The Edgar Degas (19 July 1834 – 27 September 1917) we know depicted ballet dancers. In fact, for many of us, dancers were Degas’ only subject matter, which is understandable as these were the works we were shown. Yet, he also depicted horse racing and café scenes. Moreover, he was a fine portrait artist, a skill he perfected during a three-year stay with relatives in Naples, Italy, beginning in 1856. At that time, he was also considering a career as historical painter and produced a few historical paintings.

Degas’ main subject was indeed the human figure, especially women. “Ballet dancers and women washing themselves would preoccupy him throughout his career.”[i] So would milliners, laundresses, cabaret singers and prostitutes. As Degas claimed, he was a “realist” and, earlier in his career, a social realist, as in literary realism.

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica,

“As part of his own process of engaging with modernity, he [Degas] self-consciously aligned himself with Realist novelists such as Émile Zola and Edmond and Jules Goncourt, drafting illustrations for their novels and briefly adopting a similar social descriptiveness.”[ii]

Yet, Degas would later cast away “the certainties of a state-controlled, historical culture for an art of individual crisis, even approaching the nihilism of the following generation.”[iii] Moreover, the Dreyfus Affair would elecit, on Degas’ part, a “violently anti-Semitic response” that estranged former friends.[iv]

Degas: Seascapes, Landscapes & Valery-sur-Somme

Early Outdoors Scenes

But let us return to our subject matter: the eclectic Degas. We know that he made fun of en plein air (outdoors) painters, but the above paintings prove that he devoted at least one season, 1869, to “plein-air” art. Moreover, Degas’ depictions of horses and horse racing scenes are outdoors works. Finally, Degas left seascapes, landscapes, and depictions of Saint-Valery-sur-Somme, shown below. The above paintings, two pastels, are early works depicting beaches. These are therefore very luminous works. Moreover, they could be classified as Impressionist works. The colours are muted, varied, and sea and sky nearly blend in “Beach with Sailing Boats.” In the upper part of these pastel seascapes, Degas has used a darker colour. He therefore presents a painterly rather than linear sky scape.

Sky Study, 1869

Sky Study, 1869

Later Outdoors Scenes

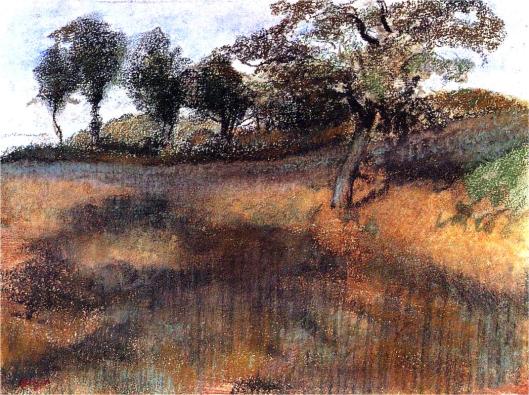

In later “plein-air” works, his subject matter changed and his works darkened accordingly. Yet, he did not change his selection of colours to a significant extent. In “Plowed Field,” shown below, as one looks up, one sees little beads: blue, mauve, dark green and silver. They illuminate his art. Here the sky is not a principal subject matter. Trees dominate “Plowed Field,” a mostly linear pastel. “Plowed Field” is reminiscent of the nineteenth-century Russian lyrical landscapes of artist Alexei Savrasov (24 May 1830 – 8 October 1897). It is also reminiscent of the “mood” landscapes created by Isaac Levitan (30 August 1860 – 4 August 1900; aged 39).

Plowed Field, 1890 (pastel)From the point of view of composition, “Plowed Field,” now above, is a gem. It features a lovely curve that begins with the largest tree, on the right side of the artwork. Degas usually placed his subject matter relatively far from the middle of his artwork. We also see curves running in opposite directions. However, we have a dark main line directly beneath the trees. I love the effect created by the very pale, silvery, beads. There is considerable movement in this painting. It is as though the trees were performing pirouettes.

Saint-Valery-sur-Somme

Degas also depicted the houses of Saint-Valerie-sur-Somme, a small community in northern France. In “Houses at the Foot of a Cliff (Saint-Valery-sur-Somme),” we have an oil painting featuring a coloured sky, but the main compositional elements are three lines: 1) a slightly broken diagonal line and, underneath, 2) a horizontal line, traced above the blue-roofed cottages and running the entire width of the canvas, beneath the cottages, 3) another diagonal line running in a direction opposite the upper diagonal line. We do not see a vanishing point, but almost. There is movement is this painting, as in “Plowed Field.”

Houses at the Foot of a Cliff (Saint-Valery-sur-Somme), 1898 (oil)

Rue Quesnoy, Saint-Valery-sur-Somme, 1898 (pastel)

Rue Quesnoy, Saint-Valery-sur-Somme, 1898 (pastel)

“Rue Quesnoy” also features lines: two narrowing vertical lines, flanked by houses and a broken and playful third line, a horizontal line consisting of trees slightly above the horizon. Again, we sense movement in Degas’ work. He guides and pleases the eye.

Our Masterpiece

But our masterpiece remains a female figure, a pastel inserted at the bottom of this post, a dancer adjusting her slipper: lines against a flat-coloured background, an example of Japonism, except that he shows a shadow. In this work, less is more.

“Artists were especially affected by the lack of perspective and shadow, the flat areas of strong color, and the compositional freedom gained by placing the subject off-centre, mostly with a low diagonal axis to the background.” (See Japonism, Wikipedia)

“The prints were collected by such painters as Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, and other artists. The clarity of line, spaciousness of composition, and boldness and flatness of colour and light in Japanese prints had a direct impact on their work and on that of their followers.”[v]

Conclusion

Once known mainly for his depiction of ballet dancers, Degas’ choice of subject matter was much broader and always appealing, even when his representation of the human form, the female figure, did not embellish his models. His art is figurative, not abstract, but his strength lies, to a large extent, in the structure of his art, or in the lines behind the figures. A successful artist during his own lifetime, he was admired by artists who followed him, including Picasso, and he remains not only a favourite but also a model, which makes him a classic.

________________________________________

[i] “Edgar Degas”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 13 Aug. 2013

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/155919/Edgar-Degas/235481/Realism-and-Impressionism>. [ii] “Edgar Degas”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 13 Aug. 2013

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/155919/Edgar-Degas/235483/Final-years>. [iii] “Edgar Degas”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 13 Aug. 2013

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/155919/Edgar-Degas/235481/Realism-and-Impressionism>. [iv] “Edgar Degas”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 13 Aug. 2013

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/155919/Edgar-Degas/235483/Final-years>. [v] “Japanism”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 13 Aug. 2013

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/301314/Japanism>.

Degas in a Green Jacket, Self-Portrait, 1856 (oil) (Photo credit: Wikipaintings)

(Please click on the image to enlarge it.)

Antonio Vivaldi (4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741),

The Four Seasons, Spring

Gidon Kremer (born 27 February 1947), violinist

London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Claudio Abbado

Degas in a Green Jacket, Self-Portrait, 1856 (oil) (Photo credit: Wikipaintings)

(Please click on the image to enlarge it.)

Antonio Vivaldi (4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741),

The Four Seasons, Spring

Gidon Kremer (born 27 February 1947), violinist

London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Claudio Abbado

Dancer Adjusting her Sandal, 1890 (pastel)

(Please click on the image to enlarge it.)

© Micheline Walker

13 August 2013

WordPress

Dancer Adjusting her Sandal, 1890 (pastel)

(Please click on the image to enlarge it.)

© Micheline Walker

13 August 2013

WordPress