Tags

anthropomorphism, Buffon, Cars, Equinoxes, exemplum, fables, Fashion, Solstices, The Art and Crafts Movement, Walt Disney

—ooo—

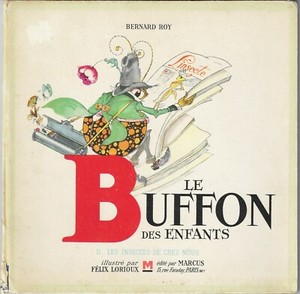

The cover of la Comtesse de Ségur‘s Les Deux Nigauds (The Two Silly Kids) is shown above, illustrated by Félix Loriaux. It has been on my bookshelves for about 70 years. It is a book intended for children written by La Comtesse de Ségur (1 August 1799 – 8 February 1874). La Comtesse de Ségur was Russian by birth. Sophie Rostophchine’s father, Count Fyodor Rostopchin, Saint Petersburg, reportedly set Saint Petersburg ablaze when Napoléon invaded Russia, in 1812. Rostopchin was accused of arson. La Comtesse and her family left Russia in 1814. They were aristocrats and, given her marriage to le Comte de Ségur, Sophie Rostopchine became a French countess. My copy shows Innocent, brother to Simplicie, wearing green pants and an olive jacket. The colours on photographs may not correspond to the original image. Lorioux is known for his use of colour. La Comtesse de Ségur‘s most famous book was Les Malheurs de Sophie (Sophie’s Misadventures), published in 1858.

Studies & Employment

Félix Lorioux (1872–1964) was born in Angers. He studied at l’École des beaux-arts de Paris, not knowing what he would design. First, it would be cars, publicity for cars, but he would work as an illustrator. He was employed by Hachette, a French publishing house, and became a notorious illustrator. Lorioux befriended Walt Disney, who hired Lorioux to illustrate Mickey and The Silly Symphony. Lorioux and Walt Disney parted ways in 1934. (See Félix Lorioux, Wikipedia). It may be that Félix Lorioux did not wish to move to the United States. By 1934, La Bande dessinée, often known as the Comics, quickly developed in France and Belgium, and thousands of Japanese prints flooded Europe. A man of his time. Félix Lorioux was therefore influenced by le Japonisme, Japanese woodblock prints, and Art nouveau. Moreover, illustrations were required when the fashion industry blossomed. They adorned La Gazette du Bon Ton and, later, fashion magazines. Artists also made posters, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec is our best example. As for interior designers, they also became more numerous. Consummate artist Bernard Boutet de Monvel, of the Boutet de Monvel dynasty, was often employed by affluent citizens of Manhattan. Bernard Boutet de Monvel died in the Azores in the plane crash that also took the life of violinist Ginette Neveu and boxer Marcel Cerdan, Édith Piaf‘s lover. Finally, Félix Florioux was first employed by Citroën, a car company. Félix Lorioux lived in a world where design and publicity were combined and where design mattered. Cars are designed. So are aeroplanes. Moreover, the Arts and Crafts Movement swept the globe, bringing art to humbler homes.

Illustrations

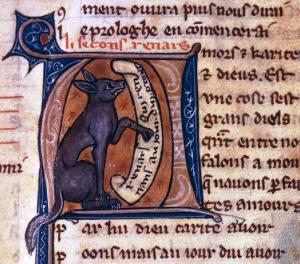

Design spread. Yet, after working for Citroën, Lorioux joined Hachette, a publishing house, and became an illustrator. He was now entering a profession that dated back centuries or more. We have looked at medieval Books of Hours that celebrated the labour of the months, seasons, solstices, and equinoctial points. These are linked to the Canonical Hours. Hesiod‘s Works and Days is an almanach.

Fables de Jean de La Fontaine

- http://www.la-fontaine-ch-thierry.net/fables.htm La Fontaine FR

- http://www.la-fontaine-ch-thierry.net/fablanglais.htm La Fontaine EN

Félix Lorioux illustrated a large number of books. However, we will start by focusing on his illustrations of the Fables of Jean de La Fontaine (8 July 1621 – 13 April 1695). His first fable is La Cigale et la Fourmi (The Cicada and the Ant).

La Cigale, ayant chanté

Tout l’été,

Se trouva fort dépourvue

Quand la bise fut venue.

Pas un seul petit morceau

De mouche ou de vermisseau.

Elle alla crier famine

Chez la Fourmi sa voisine,

La priant de lui prêter

Quelque grain pour subsister

Jusqu’à la saison nouvelle.

Je vous paierai, lui dit-elle,

Avant l’août, foi d’animal,

Intérêt et principal.

La Fourmi n’est pas prêteuse;

C’est là son moindre défaut.

Que faisiez-vous au temps chaud ?

Dit-elle à cette emprunteuse.

Nuit et jour à tout venant

Je chantais, ne vous déplaise.

Vous chantiez ? j’en suis fort aise :

Et bien! dansez maintenant.

The gay cicada, full of song

All the sunny season long,

Was unprovided and brought low,

When the north wind began to blow;

Had not a scrap of worm or fly,

Hunger and want began to cry;

Never was creature more perplexed.

She called upon her neighbour ant,

And humbly prayed her just to grant

Some grain till August next;

“I’ll pay,” she said, “what ye invest,

Both principal and interest,

Honour of insects –and that’s tender.”

The ant, however, is no lender;

That is her least defective side;

“But, hark ye, pray, Miss Borrower,” she cried,

“What were ye doing in fine weather?”

“Singing . . . nay, ! look not thus askance,

To every comer day and night together.”

“Singing! I’m glad of that; why now then dance.”

Comments

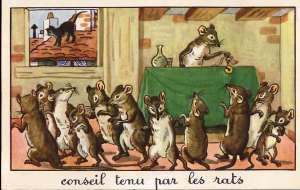

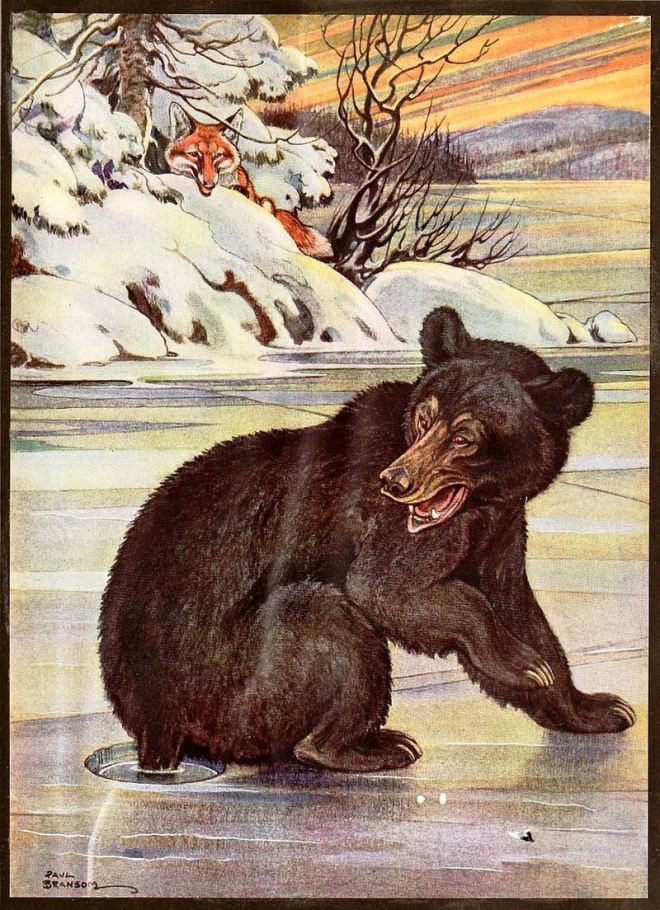

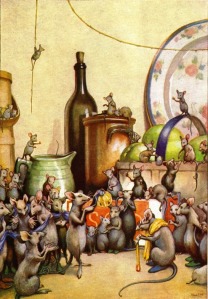

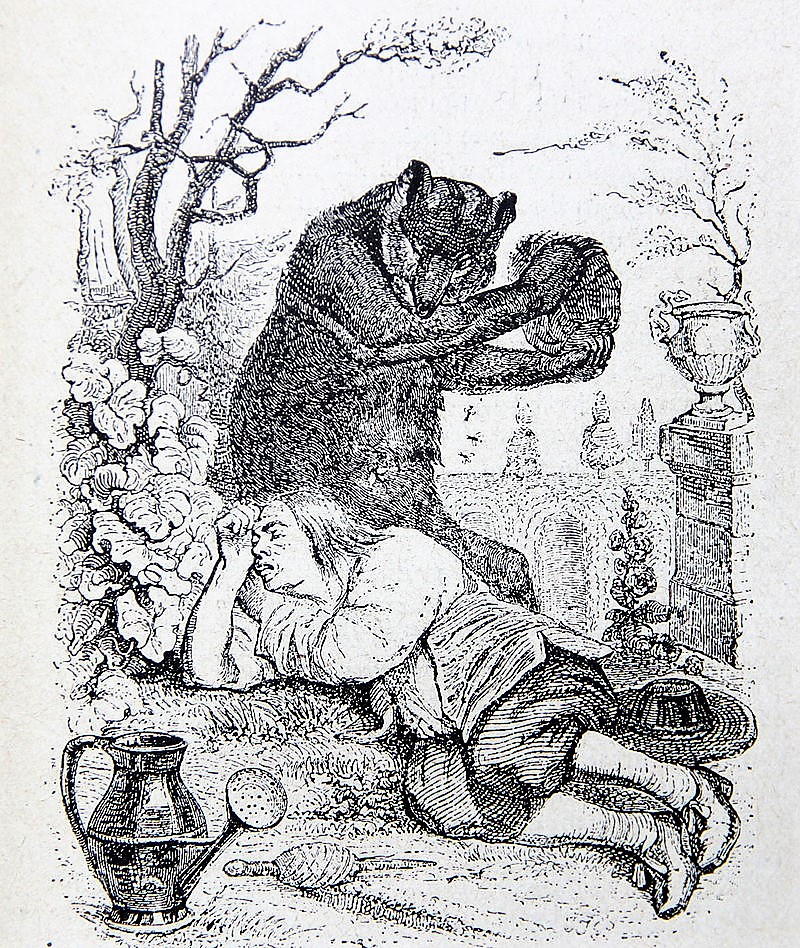

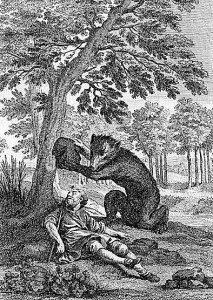

It is a little early to comment, but I must close this post. Loriaux’s illustrations of the fables of Jean de La Fontaine are anthropomorphic. Animals inhabiting fables are humans in disguise and, by and large, they are likeable, especially if the readers are children. Children who cannot read will be told about and shown an improvident animal and may say the animal is short-sighted or “silly.” However, they are unlikely to identify with the cicada or grasshopper. She should have prepared for the cold days of winter. Yet, children may prefer the improvident animal to a brighter companion. They do not like to be scolded when they make foolish mistakes and may not like the moral of our fable. It is located after the exemplum. This makes it an epimythium. The moral is a promythium if it precedes the myth or exemplum. The moral may also be the fable itself. In La Fontaine, ignoring the consequences of a certain action is a prominent lesson.

Le Buffon des enfants

Buffon, however, was not an illustrator. Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopédiste. (See George-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Wikipedia.) His animals are depicted faithfully. However, in illustrations of animals intended for children, animals be may be turned into humans. They may wear clothes, carry a watch or an umbrella, and seem disguised. Children are often attracted to camouflaged but recognizable animals. They may also expect the lion to be king and the fox to play his archetypal work as a trickster. Moreover, illustrators may give animals whose beak is long a longer beak and animals whose eyes are large, more prominent eyes, as do cartoonists. Illustrating le Comte de Buffon would not yield detailed portraits of animals who have made a mistake. It would be Le Buffon des enfants (Buffon for Children).

This conversation will be continued.

One can no longer copy texts contained in the Château-Thierry site. So, I have been very careful and I thank my colleagues.

Love to everyone 💕

RELATED ARTICLES

- An Older Orient (18 September 2016)

- A Glimpse at the Boutet de Monvel Dynasty (3 January 2016)

- The Golden Age of Illustration in Britain (30 October 2015)

- Natural Histories (3 October 2014)

- The Exceptionally Gifted: Ginette Neveu (21 August 2014)

- Allegorical Illuminated Manuscripts: the Medieval Bestiaries (20 February 2013)

- The Book of Kells Revisited (17 March 2013)

- Books of Hours, a Rich Legacy (8 February 2013)

- Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (21 December 2012)

- Jacques de Voragine & the Golden Legend (6 February 2012)

- The Fitzwilliam Book of Hours (20 November 2011)

- The Book of Kells (18 November 2011)

- The Canonical Hours and the Divine Office (19 November 2011)

______________________________

Batany, Jean, Scène et Coulisses du « Roman de Renart », Paris : Sedes (1989).

Ziolkowski, Jan, Talking Animals: Medieval Latin Beast Poetry 750-1150. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press (1993).

Zipes, Jack (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales, Oxford: Oxford University Press (2000).

© Micheline Walker

8 December 2021

WordPress

© Micheline Walker

© Micheline Walker