Tags

Canadian Confederation, John Ralston Saul, Language Laws, Rights of Englishmen, Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, Separate Schools, Sir John A. Macdonald, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, The Quebec Question, Uniform Schools

—ooo—

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/bill-96-explained-1.6460764

Less than two weeks from now, Canadians will celebrate what is viewed as their birthday. In 1867, the Province of Canada, future Quebec and Ontario, and two maritime provinces, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, confederated. This year, Canada’s birthday follows the passage of language laws in Quebec. Bill 96 was voted into law on 24 May 2022 and took effect on 1st June. It has generated controversy, so details cannot be revealed accurately. English-speaking Quebecers will lose “rights.”

In earlier posts, I noted that Canadian Confederation eliminated instruction in the French language in Canadian provinces outside Quebec. One often reads that Confederation ended Catholic public schools, but the French were Catholics. They were the product of French absolutism, a form of centralisation demanding that the French speak one language, practice one religion, and be governed by one king: Louis XIV. After the fall of Nouvelle-France, the French language and devotion had waned in a province that would later be described as “priest-ridden,” but remedies were at hand.

First, the Quebec Act of 1774 restored former Seigneuries, and Catholics had to pay tithe (la dîme) to the clergy, which “habitants” protested. However, the Quebec Act allowed French-speaking Canadians to enter the civil service and run for office without renouncing their faith. Second, England asked the bishopric of Québec to welcome émigrés priests. Fifty-one (51) priests travelled to the former New France (See French immigration in Canada, The Canadian Encyclopedia). I have mentioned l’abbé Sigogne in an earlier post. L’abbé Sigogne was an émigré priest who worked in Acadie, the current Nova Scotia. He was rather harsh on Acadians, his flock, but very loyal to Britain, the country that spared him the guillotine. He spoke English and befriended Thomas Chandler Haliburton. After the French Revolution, Lower Canada also welcomed a few émigrés families and Count Joseph-Geneviève de Puisaye attracted forty people to York, north of the current Toronto, Upper Canada. (See French immigration in Canada, The Canadian Encyclopedia.)[1]

Émigrés priests revitalised waning Catholicism in the former New France and they founded colleges (Séminaires). Many graduates of these colleges became priests. Others usually entered a profession. They were lawyers, notaries, medical doctors, and teachers. The majority of graduates were conservative, but higher learning often leads to liberalism. (See L’Institut Canadien, Britannica.) Liberal-minded graduates of colleges opposed Ultramontanism, but ultramontanism remained the dominant ideology in the province of Quebec until the late 1940s. It ended with the publication of Refus global (1948), a manifesto written by artists, and the Asbestos strike (1949). Refus global and the Asbestos strike were the turning point.

Throughout the 19th century, as industries developed, the Church in Quebec recommended compliance on the part of workers. So, factory workers, including the Irish, lived on a small salary and were not promoted. In the eyes of the clergy, living in poverty could guarantee salvation. Jansenism exerted considerable influence in Quebec. The more one suffered, the better.[2] However, during the Asbestos strike, the archbishop of Montreal, Joseph Charbonneau, sided with the strikers, some of whom were severely beaten. This had not happened before. Monseigneur Charbonneau was “exiled” to Victoria (B. C.), by Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis. Monseigneur Charbonneau died a year before the beginning of Quebec’s Quiet Revolution, la Révolution tranquille.

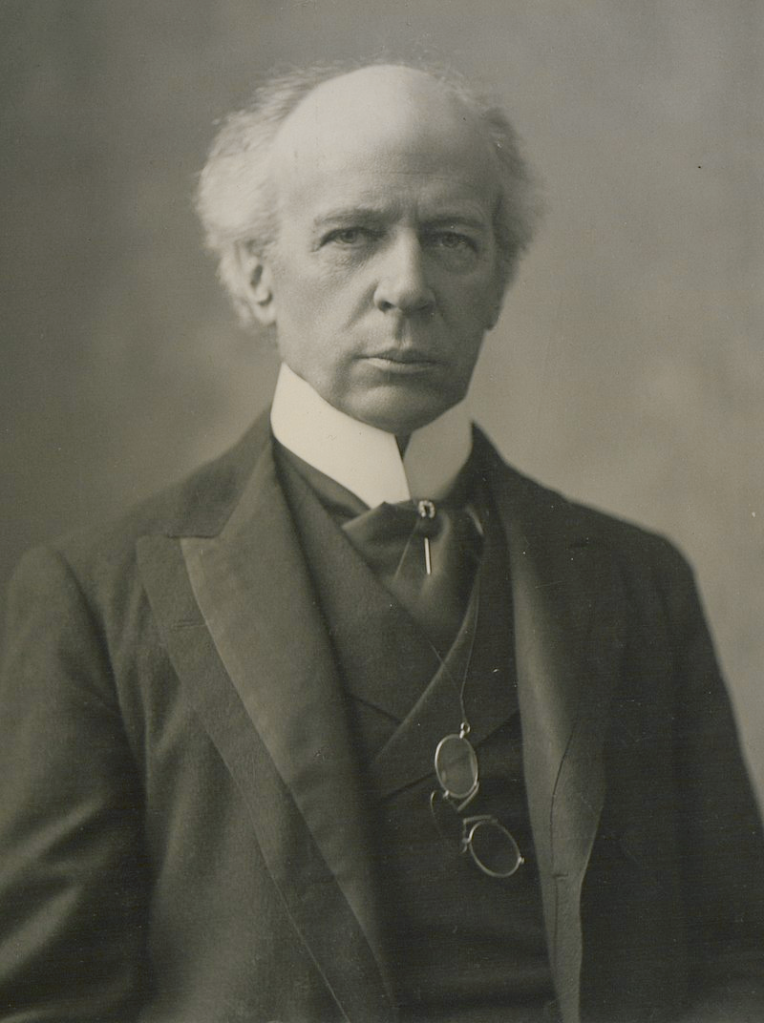

According to Raymond Tanghe[3], Canadian Prime Minister (1896-1911) Sir Wilfrid Laurier tried to pass a motion favouring a degree of tolerance regarding instruction in the French language. Sir Wilfrid Laurier‘s motion was defeated and Sir Charles Tupper called for an election. Priests told Quebecers not to vote for Liberal candidates (the party). If they did, they would commit a “mortal sin.” Rome ruled in favour of a separation between Catholicism and politics.

Canada was very British. Its national flag, the Canadian Red Ensign, represented Canada as a nation until it was replaced by the maple leaf design in 1965. (See Canadian Red Ensign, Wikipedia.)

Confederation

Let us return to Confederation (1867). To a vast extent, Quebec’s language laws stem from John A. Macdonald’s categorical refusal to allow the creation of “separate” schools, i.e. French-language instruction outside Quebec. However, Quebec had not entered Confederation unreservedly. It was allotted a province where French-speaking Canadians could maintain their language and their faith, which Québécois remember. Moreover, an alliance with Britain could preclude annexation by the United States. Living in the British Empire promised safety and the prospect of election to the Assembly. Confederation would stretch Canada from sea to sea, a lovely vision. Railroads were being constructed.

However, in 1867, when British North America became the Dominion of Canada, several anglophones, many of whom were former citizens of the Thirteen Colonies, still entertained such notions as the Rights of Englishmen.

The Rights of Englishmen is an assumed group of rights that had its roots in the basic rights granted in the Magna Carta. The idea reached its peak during the British settlement of North America. By this time colonial Englishmen felt they were entitled to certain additional rights and liberties.

(See Rights of Englishmen, Wikipedia.)

During the late 18th century and most of the 19th century, the British Empire was at its zenith, which reinforced placing the British in a superior position. The Rights of Englishmen was a concept that could justify seeking independence from Britain, the motherland. The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) created the independent United States of America, a republic. However, the same motivation, the Rights of Englishmen, could lead the inhabitants of the former Thirteen Colonies to move to a British Colony where they expected to be treated as Englishmen. United Empire Loyalists left the United States to settle in British North America where they were given large lots:

The Crown gave them land grants of one lot. One lot consisted of 200 acres (81 ha) per person to encourage their resettlement, as the Government wanted to develop the frontier of Upper Canada. This resettlement added many English speakers to the Canadian population. It was the beginning of new waves of immigration that established a predominantly English-speaking population in the future Canada both west and east of the modern Quebec border.

(See United Empire Loyalists, Wikipedia.)

The Manitoba Schools Question

As of Canadian Confederation (1867), Quebec would have French-language and Catholic Schools, as well as English-language Protestant schools. But as immigrants settled in other provinces, they had to attend non-confessional English-language schools. Outside Quebec, most French-speaking Canadians were assimilated. Sir Wilfrid Laurier, then prime minister of Canada, oversaw the “addition” (The Canadian Encyclopedia) of Alberta and Saskatchewan to Confederation. The only compromise he could reach was the Greenway-Laurier Compromise (Manitoba), which wasn’t much.

The Laurier-Greenway compromise was a regulation on schools named after Canadian Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier and Manitoba Premier Thomas Greenway. This compromise came after the adoption in 1889 of the notorious Official Language Act, which made English the sole language of Manitoba government records, minutes, and laws. Other laws abolishing French in all legislative and judicial spheres followed, leading to the disappearance of Catholic schools.

(The Greenway-Laurier Compromise, 1896.)

The compromise is described as follows:

The Laurier-Greenway compromise contained a provision (section 2.10) allowing instruction in a language other than English in “bilingual schools,” where 10 or more students in rural zones and 25 or more in urban centres spoke this language.

(The Greenway-Laurier Compromise, 1896.)

Thomas Greenway would be the Premier of Manitoba in 1888, three years after Louis Riel‘s execution on 16 November 1885. Thomas Greenway had been a friend of Sir John A Macdonald in the earlier years of his career. He

is remembered, however, for the elimination of minority educational rights for Roman Catholics; the MANITOBA SCHOOLS QUESTION dominated provincial and federal politics during his years as premier. He remained leader of the provincial Liberals until his election as MP for Lisgar in 1904.

(See Thomas Greenway, The Canadian Encyclopedia.)

The Manitoba Schools Question & the Quebec Question

- the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (1963-1969)

- the Official Languages Act of 1969

The MANITOBA SCHOOLS QUESTION migrated to provinces other than Manitoba and it resulted in a mostly unilingual Canada. In fact, the “schools question” became “la question du Québec,” the Quebec question. As I noted above, immigrants to Canada who settled outside Quebec were educated in “uniform” schools, or schools where the language of instruction was English. Therefore, outside Quebec, most Canadians were anglophones. This created a malaise in Quebec and this malaise led to both the Quiet Revolution and the establishment, by Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson, of a Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (19 July 1963-1969).

The Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism

The mission entrusted to the royal commission was

to inquire into and report upon the existing state of bilingualism and biculturalism in Canada and to recommend what steps should be taken to develop the Canadian Confederation on the basis of an equal partnership between the two founding races, taking into account the contribution made by the other ethnic groups to the cultural enrichment of Canada and the measures that should be taken to safeguard that contribution.

(See Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, Wikipedia.)

The Commission was co-chaired by André Laurendeau, publisher of Le Devoir, and Davidson Dunton, president of Carleton University. The Commission recognized, officially, that Canada was a bilingual and bicultural country. Canada’s founding nations, other than its First Nations, or Amerindians, were France and Britain. The work of the Commission led to the Official Languages Act of 1969. However, its findings could not justify the creation of French-language schools across Canada. These were created in Acadian communities and in certain districts. During the century separating Confederation (1867) and the Official Languages Act (1969), Canada became a largely English-language country. Yet, in the 1970s, French immersion schools were created, as well as summer immersion programmes. English-speaking Canadians also formed an influential association: Canadian Parents for French.

Bilingualism has its advantages. It can lead to a fine position in the Civil Service, in the Military, in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and elsewhere. I taught French to civil servants. At first, some expressed reticence. French was being “thrown down their throat.” Two weeks later, or by coffee break, these students enjoyed learning French.

History could not be rolled back, but the Official Languages Act of 1969 was a blessing. It recognized that Canada’s founding nations, other than its First Nations, were France and Britain. However, French-speaking Canadians had been recognized earlier. Governor James Murray refused to assimilate Britain’s new subjects and, as noted above, Sir Guy Carleton negotiated the Quebec Act of 1774 which restored the Seigneurial System. Habitants would work for their seigneur and provide tithe (la dîme) to the clergy. The Test Act was no longer required for an applicant to join the Civil Service or to run for office as a member of Parliament. The arrival of the United Empire Loyalists in British North America changed matters. So did Confederation. French-speaking Canadians were a minority and most lived in Quebec.

Quebec’s Language Laws

Five years after the passage of the Official Languages Act of 1969, Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa‘s Liberal Government passed Bill 22. In 1974, Quebec declared itself a unilingual province. In 1977, Quebec passed Bill 101, the Charter of the French language. Bill 101 dictated unilingual posting and the enrolment of immigrants in French-language schools. English-speaking Canadians of British ancestry could be educated in English-language schools. Other English-speaking Canadians could not. (Education is a provincial portfolio.) Bill 22 did not please English-speaking Montrealers, nor did Bill 101. Many anglophones left Montreal and Toronto gained status. Moreover, Quebec’s language laws often affected the life and the career of French-speaking Canadians living outside Quebec. These individuals had to explain Quebec and compensate for language laws. Teachers had to create French-speaking Canadians. Besides, where would immigrants find refuge? Most immigrants are seeking a peaceful environment. During WW II, several French-speaking European royals lived in Quebec.

Bill 22 and Bill 101 created tension, and so did Quebec’s two referendums on sovereignty: the 1980 Referendum (20 May 1980; defeated by a 59.56% margin) and the 1995 Referendum (30 October 1995; defeated by a 50.58% margin). The first referendum took place four years after René Lévesque‘s Parti Québécois was elected (1976). Both referendums proposed sovereignty (independence), but the wording of the 1995 referendum included a reference to a “partnership” with Ottawa:

Do you agree that Québec should become sovereign, after having made a formal offer to Canada for a new economic and political partnership, within the scope of the Bill respecting the future of Québec and of the agreement signed on 12 June 1995?

(See Quebec Referendum (1995), The Canadian Encyclopedia)

Conclusion

I wish Sir John A. Macdonald had not created the “schools” question. Sir Wilfrid Laurier might have been able to support the re-introduction of French as a language of instruction had the French not linked language and faith inextricably. But I doubt that religion played as important a role as the language of instruction:

Despite Macdonald's reluctance, Manitoba entered Canada as a province. English and French-language rights were safeguarded in the new legislature and the courts. Protestant and Roman Catholic educational rights were protected, but the right to education in either English or French was not.(See Manitoba and Confederation, The Canadian Encyclopedia.) Bold characters are mine.

As you know, I spent forty happy years in English-language provinces and had decided never to return to Quebec because of disputes between anglophones and francophones. I knew I could not survive in such a climate. Truth be told, I am not doing very well.

Canada’s two founding nations were separated for a century to the detriment of French-speaking Canadians and Canadian unity. How would French-speaking Canadians save their language? Quebec passed language laws, and these have generated acrimony. I have heard Canadians express pride because a family member was educated at an English-language Quebec University without learning French. Anglophones can live in Quebec without using French. The Eastern Townships is a bilingual region of Quebec because it was settled by United Empire Loyalists. My grandfather, who was born and raised in the Townships, could not speak a word of French. However, Quebec’s language laws erode what English-speaking Canadians view as their rights. As for Québécois, they monitor the survival of the French language, which they view as their right. They pass abrasive language laws. Quebec is a unilingual province inside a bilingual Canada.

It could be that such a notion as the Rights of Englishmen had survived in the collective memory of Quebecers of British origin. As for French-speaking Canadians, I would not exclude the negative consequences of being “conquered.” They may look upon themselves as a defeated people.

I have a photocopy of Hubert Aquin‘s article entitled L’Art de la défaite, published in Liberté, 1965. Aquin writes that the Rebellion of 1837-1838 is irrefutable proof that French Canadians are capable of anything, including stirring up their own defeat.[4]

La rébellion de 1837-1838 est la preuve irréfutable que les Canadiens français sont capables de tout,voire même de fomenter leur propre défaite.

Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine built a bilingual and bicultural Canada. English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians are compatible and equal. English-speaking Quebecers do not have to learn French. Fortunately, many anglophone Canadians have attended and still attend a private French school or are sent to a French school in Switzerland. Enrolment in a private school can be costly. These individuals have “grace.” I’ve known many and married one.

John Ralston Saul attended an Alliance Française school. He wrote a book on the Great Ministry of Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine. (See John Ralston Saul, Wikipedia.) Many share the view that Canada was born before Canadian Confederation.

He argues that Canada's complex national identity is made up of the "triangular reality" of the three nations that compose it: First Peoples, francophones, and anglophones. He emphasizes the willingness of these Canadian nations to compromise with one another, as opposed to resorting to open confrontations. In the same vein, he criticizes both those in the Quebec separatist Montreal School for emphasizing the conflicts in Canadian history and the Orange Order and the Clear Grits traditionally seeking clear definitions of Canadian-ness and loyalty. (See John Ralston Saul, Wikipedia.)

Isn’t it possible to study French or English at school, as a second language? It is not that old-fashioned an idea. After all, Quebec managed the Pandemic in both French and English.

But I must go … This post is too long.

RELATED ARTICLES

- Canadiana 1 (page)←

- Canadiana 2 (page)←

- Alexis de Tocqueville & John Neilson: a Conversation, 27 August 1831 (13 May 2021)

- Alexis de Tocqueville & John Neilson (13 May 2021)

- La Question des écoles / The Schools Question. 2 (28 April 2021)

- La Question des écoles (24 April 2021)

- Would that Robert Baldwin and Sir Hippolyte La Fontaine … (22 October 2020)

- La Saint-Jean-Baptiste & Canada Day (6 July 2015) ⬅️

____________________

[1] Micheline Bourbeau-Walker, « Le Récit d’Acadie : présence d’une absence », in Édouard Langille et Glenn Moulaison, éditeurs, Les Abeilles pillotent: mélanges offerts à René LeBlanc, Revue de l’Université Ste-Anne, Pointe-de-l’Église, 1998, pp. 255-275. ISBN 2-9805-909, ISSN 0706-8116

[2] Denis Monière, Le Développement des idéologies au Québec des origines à nos jours, Montréal, Éditions Québec/Amérique, 1977, p. 209.

[3] Raymond Tanghe, Laurier, artisan de l’unité canadienne, MAME, Figures Canadiennes, 1960, pp. 48-49.

[4] Hubert Aquin, « L’Art de la défaite », Liberté, Volume 7, numéro 1-2 (33-38), janvier–avril 1965, p. 33.

—ooo—

Love to everyone 💕

© Micheline Walker

21 June 2022

(revised 22 June 2022)

WordPress