Tags

Antwerp, Dutch Golden Age of painting, Eighty Years' War, Flanders, Flemish Baroque artist, Hélène Fourment, History, Peter Paul Rubens, Suzanne Lunden, The Burgundian State, The Duchy of Brabant, Twelve Years' Truce

Suzanne Fourment Lunden, portrayed above, was Baroque Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens‘s sister-in-law. In 1630, four years after Rubens’s first wife, Isabella Bran(d)t, died of the plague, fifty-three-year-old Rubens married sixteen-year-old Hélène Fourment. His first marriage to Isabella Brant had been a very happy marriage, except for the loss of Clara Serena, the couple’s first child, a daughter. Clara Serena has been featured briefly in an earlier post and will be featured again. Rubens’s marriage to Hélène Fourment was also a happy but short union. It lasted ten years. Peter Paul Rubens died in 1640 and Hélène remarried. Rubens was a family man, which, somehow, I could not “sense” from his many portraits. He loved his profession, and he loved his family.

Susanna Fourment Lunden has very large eyes. It may have been a characteristic of portraits executed during the Dutch Golden Age of painting, but Rubens depiction of Marie de’ Medici, Louis XIII’s mother and Anne of Austria, Louis XIII’s wife are formal portraits. However, Netherlandish artists would produce tronies, or portraits showing a facial expression.

The Dutch Golden Age of painting

- the word Dutch,

- the wars of religion,

- the Peace of Münster, 1648 (Eighty Years’ War)

- the Peace of Westphalia, 1648 (Thirty Years’ War)

- the Congress of Vienna. (1814-1815)

I’m about to post articles on the Dutch Golden Age of painting, and Rubens will be our main figure. Baroque Flemish artist and diplomat Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). He is associated with the Dutch Golden Age of painting, and he will be our main figure. After spending several years in Italy, Peter Paul Rubens settled in Antwerp (Anvers), a Flemish city, in the Duchy of Brabant during the Twelve Years’ Truce (1609-1621). In 1609, Antwerp was located in what would become the partitioned Duchy of Brabant. However, he died in 1640, before the end of the Eighty Years’ War and the Peace of Münster. Rubens belongs quite literally to the Dutch Golden Age of painting. Yet, the word Dutch may be confusing. The Netherlands was partitioned, but according to Wikipedia,

"The origins of the word Dutch go back to Proto-Germanic, the ancestor of all Germanic languages..." (See Dutch People, Wikipedia.)

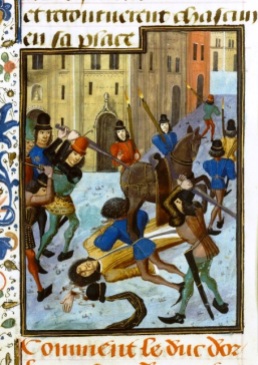

The Eighty Years’ War

The Netherlands fought the Eighty Years’ War (1568-1648), which was both a war of independence from the Spanish Habsburgs and a war of religion. The inhabitants of the Southern Netherlands, the future Belgium, were mostly Catholics, but their neighbors to the North, the Dutch, were Protestants. The Eighty Years’ War is often called the Dutch Revolt. The Dutch Republic, today’s Netherlands, was proclaimed at the Peace of Münster, in 1648. The people of Antwerp (Anvers) remained under Spanish rule and Brabant was partitioned. North Brabant forms part of the Dutch Republic.

The Kingdom of the Netherlands

Today, the Dutch live in the Netherlands (Nederland), which includes North Brabant. However, the Kingdom of the Netherlands was not formed until the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815), which closed the Napoleonic Wars (so was Luxembourg):

"All agreed upon ratifying the new Kingdom of the Netherlands, which had been created just months before from formerly Austrian territory." (See Congress of Vienna, Wikipedia.)

Belgium

As noted above, Peter Paul Rubens settled in Antwerp (Anvers), a Flemish city (Flanders) located in the Duchy of Brabant. Antwerp flourished during the Twelve Years’ Truce (1609-1621). It is now located in Belgium, a country whose independence was not recognized until the 1830 London Conference. This decision was opposed until the Treaty of London (1839).

The inhabitants of Antwerp are Flemings and speak Flemish, but the Low Countries had been the Burgundian Netherlands beginning with Philip the Bold (le Hardi), under French Valois monarchs. The people of Belgium also speak French and some speak Walloon, a threatened Romance language

Philip II was the founder of the Burgundian branch of the House of Valois. His vast collection of territories made him the undisputed premier peer of the Kingdom of France and made his successors formidable subjects, and later rivals, of the kings of France. (See Philip II the Bold, Wikipedia.)

I would like to write more on the origins of European countries, but it is a very complex process. I will let you discover. Maps are useful. However, I will note that the Romans conquered future European countries. They conquered Belgica. Later, sons and daughters inherited large territory and a marriage was used to acquire lands. (See Philip I of Castile and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Philip I (Habsburg) was born in Bruges (Flanders), but he married Joanna of Castille. They are the parents of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Joanna is referred to as Joanna the Mad. She was kept in confinement by her son, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. No one can tell whether she was “mad.” Her sister Catherine of Aragon married Henry VIII of England. Members of European Royal families are related.

Peter Paul Rubens‘s Antwerp (Anvers) forms part of today’s Belgium and Antwerp is Flemish. However, both the Netherlands (Nederland) and Belgium are Pays-Bas and referred to as Pays-Bas or Low Countries. Belgium is Jacques Brel‘s plat pays (flat land, flakke land). Brel is of Flemish origin, but he found fame singing in the French language.

Illuminated Manuscripts

For our purposes, it may suffice to remember the Limbourg Brothers (Herman, Paul, and Johan), miniaturists. They originated from Nijmegen and are associated with the Burgundian State. The Limbourg Brothers’ finest legacy is Jean de France, duc de Berry’s Très Riches Heures, an illuminated Book of Hours. The Limbourg Brothers and Jean de France are believed to have died of the plague in 1416, before completing the Très Riches Heures. Jean de France’s Très Riches Heures was further embellished by Barthélemy d’Eyck. The Limbourg brothers’s uncle was Jean Malouel, Maelwael. Malouel was a miniaturist who worked in Paris for Philip the Bold (le hardi). The Limbourg brothers learned the craft of goldsmithing in Paris. Before Jean de France asked the Limbourg Brothers to illuminate his Très Riches Heures, Philip the Bold commissioned a Bible Moralisée from the Limbourg Brothers, Paul and Johan. It was a four-year contract. Philip did not see his Bible Moralisée.

From surviving documents, it is known that in February 1402 Paul and Johan were contracted by Philip [the Bold] to work for four years exclusively on illuminating a bible. This may or may not have been the Bible Moralisée (Ms. fr. 166) in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris), which is indisputably an early work by the Limbourg brothers. Philip II died in 1404 before the brothers had completed their work. (See Limbourg Brothers, Wikipedia)

The Limbourg brothers also produced a Belles Heures de Jean de France, Duc de Berry. It is housed in the Cloisters at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

“Genre” Art, “Still Lifes,” “tronies:” diversity

It seems the people of the Netherlands, Belgium and the Netherlands have long been very good artists. They were also fine jewelers and cut diamonds.

Finally, their subject matters are varied and they were artfulness went beyond the canvas or boards : genre art, tiles (Blue Delft), tronies, tapestries, etc.

In my last post, Winter Scenes, we saw examples of Hendrick Avercamp‘s “genre art.” Avercamp’s winter scenes feature people going about their everyday tasks and recreation during winter. Johannes Vermeer also depicted people going about their everyday tasks, but they are inside houses and exerted considerable influence on interior decoration.

Vermeer was born in Delft. Delft tiles are a baseboard in the painting below. I had noticed this detail, but so did Wikipedia. The Music Lesson, below, shows a mise en abyme created by the mirror above the virginal. The word abyme suggests infinity. The mirror above the virginal does not reproduce the entire scene, but we see the face of the music student.

Public Domain

File:Johannes Vermeer – Het melkmeisje – Google Art Project.jpg

Created: circa 1660 date QS:P571,+1660-00-00T00:00:00Z/9,P1480,Q5727902

The Twelve Years’ Truce

Peter Paul Rubens settled in Flemish Antwerp (Anvers) during a Twelve Years’ Truce (1609-1621) in the Eighty Year’s War, “an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands,” and a war of religion. The Netherlands was ruled by Spanish Hapsburgs. It is my understanding that Holland was not a country until the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Belgium gained its independence in 1830, a few years after the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815), which began before the Battle of Waterloo and resumed after Napoleon fell at the Battle of Waterloo. The interruption is known as les Cent-Jours, the Hundred Days.

During the Dutch Golden Age of painting, the 17th century mainly, genre painting gained considerable popularity. But artists also depicted their history, including ships, and portraits, from royals to commoners. Rubens and Rembrandt made tronies. The art of such artists as Rembrandt, Peter Paul Rubens, Johannes Vermeer, Anthony van Dyck (who apprenticed with Rubens), and others, is classified as Dutch Golden Age painting. Peter Paul Rubens was also a Flemish Baroque artist. Baroque art is considered less severe than Mannerism (the Reformation). Rubens also drew tapestries.

I apologize for a long silence. My friend John is moving to Saint-Lambert, on the south shore of the St Lawrence River, near Montreal. Since childhood, I have designed hundreds of houses and interiors. I wish one had come true. I do not expect to see John again.

RELATED ARTICLES

- Dutch tapestries (See Christies.com’s)

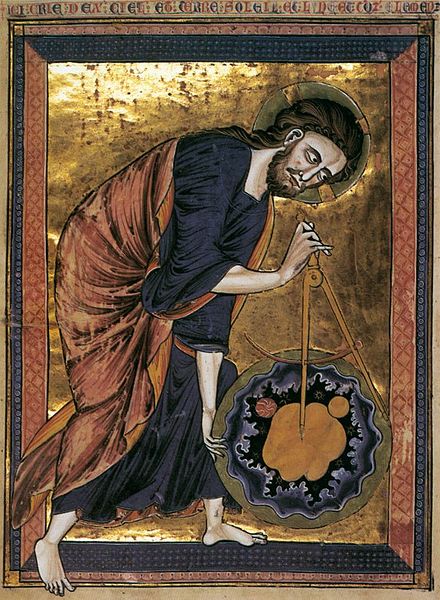

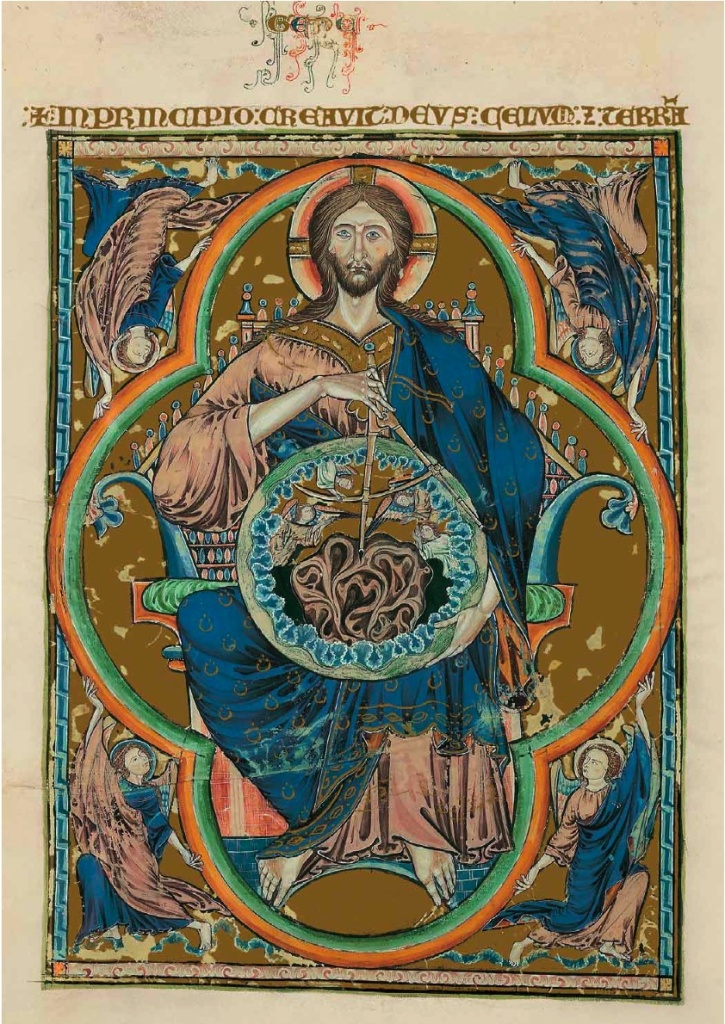

- God the Architect (19 February 2021)

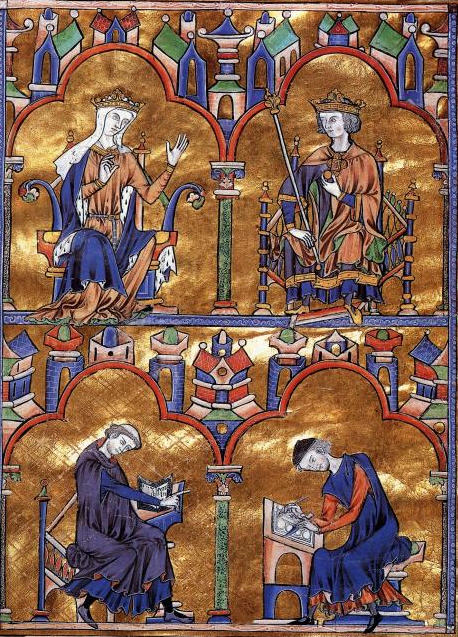

- The Bible of Saint Louis, Toledo (22 February 2021)

- Bibles moralisées: 13th-century France (27 February 2021)

- God the Architect (19 February 2021)

- The Arnolfini Portrait: mise en abyme (3 December 2014)

- Music for the Très Riches Heures and the Book of Kells (19 November 2011)

- Les Très Riches Heures de Jean de France, duc de Berry (17 November 2011)

—ooo—

Further information on the Dutch Golden Age of painting

See:

- The Girl with a Pearl Earring (Wikipedia)

- Louis I (France) (Britannica)

- Dutch Revolt (history)

- Dutch Art, Wikipedia

- Genre Art, Wikipedia

- Still lifes, Wikipedia

- Flemish Baroque Art, Wikipedia

- The Hague School (excellent entry),Wikipedia

- Tronies (portraits displaying an expression)

- Dutch tapestries (See Christies.com’s)

The Burgundian State or the Netherlandish Renaissance

- Books of Hours, Wikipedia (illuminations)

- Limbourg Brothers, Wikipedia

- Jean Malouel (Jan Maelwael), Wikipedia

Jacques Brel (le grand Jacques)

Jacques Brel à l’Olympia

© Micheline Walker

5 May 2023

WordPress