La Fontaine’s Fables: Page as Post

15 Friday Jun 2018

Posted in Beast Literature, Fables

15 Friday Jun 2018

Posted in Beast Literature, Fables

02 Thursday Mar 2017

Posted in Beast Literature, classification, Fables

Tags

Æsop, classification, eText, fables, illustrations, La Fontaine

Walter Crane, ill. Gutenberg #25433

The sites listed below may be very useful. Posts about a particular fable may contain classification or cataloging information, but not necessarily. The Project Gutenberg has published very fine collections of Æsop’s Fables, including illustrations. La Fontaine is also online, most successfully. These collections are old, but they are the classics.

© Micheline Walker

1 March 2017

© Micheline Walker

1 March 201706 Monday Oct 2014

Posted in Beast Literature, Fables

Tags

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Bruin the Bear, classification, It's no skin off my nose, jurisprudence, Le Jugement de Renart, Reynard's Judgement, Roman de Renart

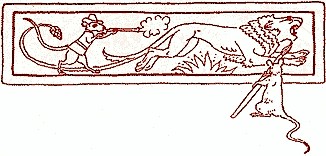

The picture featured above shows the Lion king, Noble. In Branch I, of the Roman de Renart, Le Jugement de Renart[1], the various animals, barons, meet at Noble the Lion’s court that doubles up as a court of justice. Ysengrin tells about his wife Hersent who has been raped when she got stuck in a hole. (The Roman de Renart is not in chronological order.)

The Lion does not think he can charge Renart with rape as the charge might not “stick.” There is a “history” (“branche” II)between Dame Hersent and Renart, which is known. Nevertheless, when she gets caught in a wall and Renart takes advantage of Dame Hersent, it is rape. It is in Renart’s “nature” (character) to avail himself of every opportunity.

Although a charge of “rape” might not “stick,” the other animals gathered at the Lion’s court come forward to tell Noble that Renart has wronged them time and again. For instance, he has eaten many of their relatives. Hearing their complaints, the king, Noble the lion, decides he now has sufficient reasons to have Renart brought to court, the king’s court of law. Renart’s trial and the discussion that precedes his being brought to trial is masterful. Renart’s trial is a building block in the development of European jurisprudence and has been identified as such.[2]

Renart et Dame Hersent, br. II (Photo credit: BnF)

Bruin the bear is the first “ambassador” to travel, on horseback, to Maupertuis, Renart’s, fortress. As you may suspect, Renart is not about to follow Bruin to court. Our red fox is the trickster extraordinaire, so he tells Bruin to put his snout down into a slit in a log that is secured by wedges. According to Renart, that is where Lanfroi the forester keeps his honey.

As it is known “by universal popular consent,” bears love honey. Our modern Winnie-the-Pooh gets stuck in a house because he has eaten so much honey he cannot get out the way he came in. He is like Æsop’s swollen fox (“The Fox and the Weasel.” Perry Index 24). To get out, Winnie-the-Pooh must first lose weight. Similarly, Bruin cannot resist looking down the opening in the oak tree he is told contains honey. That is in his “nature.”

By now, Renart is at a distance to protect himself from Lanfroi, but Bruin puts his nose inside the opening in the tree at which point the wedges are removed and he gets caught, or “coincé” (coin = wedge and corner). He sees Lanfroi and “vilains,” villagers, rushing to attack him. Therefore, knowing that he will lose his life if he does not flee, Bruin sacrifices the skin “off [his] nose,” gets on his horse, and travels back to court. When he arrives at court, he is bleeding profusely and faints. “Renart t’a mort” (Renart killed you,” says the king (br. I, v. 724).

Bruin seems to be suffering. However, according to Dr. Jill Mann,[3] the translator (into English) of the Ysengrimus, written in 1149 -1150, the birthplace of both Reinardus (Renart) and Ysengrimus (Ysengrin the wolf), the various animals of the Ysengrimus do not suffer.

The Ysengrimus, a 6,574-line fabliau written in Latin elegiac verses, is the Roman de Renart‘s (1274 – 1275) predecessor. Dr. Mann compares the fox and other animals to cartoons where a cat is flattened by a steamroller, but fluffs up again (Jill Mann, p. 11).

“The recrudescent power of the wolf’s skin [bear’s skin] is reminiscent of the world of the cartoon, where the cat who is squashed flat by a steam-roller, is restored to three dimensions in the next frame.” (Mann, p. 11)

In other words, Reynard the Fox is a forgiving comic text, which allows for devilish pranks that do not harm animals and human beings. They may scream, for appearances, but they return to their normal selves.

Authorship of Ysengrimus has been challenged, but the Ysengrimus exists and it was rewritten in various European languages, the languages of the Netherlands and German, in particular. At any rate, it is of crucial importance that famed translator and printer William Caxton (c. 1415 – c. March 1492) wrote an English version of Reynard the Fox. (See William Caxton – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.) (This translation is available online: The History of Reynard the Fox.)

Reynard the Fox had to be popular in England as otherwise the expression “it’s no skin off my nose” could not be traced back, albeit hypothetically, to the Reynard cycle. In France, the Roman de Renart was so popular that goupil, the French word for fox, was replaced by Renart, but La Fontaine uses the modern spelling: renard. Now, if the fox lost his name goupil to become Renart, the Roman de Renart may also have influenced the English language.

Given the popularity and wide dissemination of Reynard the Fox, crediting a linguistic element to Reynard the Fox makes sense. In fact, crediting a linguistic element to a popular fable often makes sense. These stories were in circulation. Persons who could not read were told about Reynard, just as they were told Jacobus de Voragine‘s Golden Legend.

According to Wikipedia,

“Ysengrimus is usually held to be an allegory for the corrupt monks of the Roman Catholic Church. His [Ysengrimus’] greed is what typically causes him to be led astray. He is made to make statements such as “commit whatever sins you please; you will be absolved if you can pay.”[4]

One could buy indulgences and do penance in purgatory:

“purgatory, the condition, process, or place of purification or temporary punishment in which, according to medieval Christian and Roman Catholic belief, the souls of those who die in a state of grace are made ready for heaven.”[5]

Obviously, the Roman de Renart was not written for children, but there are children’s adaptations of its many tales. In such versions, Renart does not rape Dame Hersent and when the wolf loses his tail to escape “vilains” who will kill him, he feels no pain. The Roman de Renart includes the tail-fisher motif (ATU 2; Perry Index 17 and (“The Fox with the Swollen Belly”) (Perry Index number 24). (See RELATED ARTICLES)

—ooo—

In A. A. Milne‘s[6] Winnie-the-Pooh, Eeyore loses a tail, which may remind one of the Tail-Fisher (ATU 2), but the tail is not severed or caught in the ice. The tail is lost but will be found. As for Bruin the bear’s nose, it will grow back.

Such is not the case with the Æsopic fox or La Fontaine “Renard ayant la queue coupée.” Besides, Bruin’s nose is caught just as Ysengrin’s tail is caught in the ice which forces him to lose it in order to survive.

There are differences between ATU 2 and our Æsopic fables as well as similarities. But what is fascinating is that Bruin’s sad encounter with Renart and Lanfroi the forester may have helped shape the English language: “It’s no skin off my nose.”

Let this be our conclusion.

Wishing all of you a good week.

RELATED ARTICLES

Sources and Resources

____________________

[1] Jean Dufournet & Andrée Méline (traduction) et Jean Dufournet (introduction), Le Roman de Renart (Paris: GF Flammarion, 1985), pp 72-79.

[2] Jean Subrenat, “Rape and Adultery: Reflected Facets of Feudal Justice in the Roman de Renart,” in Kenneth Varty, ed. Reynard the Fox: Social Engagement and Cultural Metamorphoses in the Beast Epic from the Middle Ages to the Present (New York & Oxford: Berghahn, 2000), pp. 16-35.

[3] Jill Mann “The Satiric Vision of the Ysengrimus,” in Kenneth Varty, ed. op. cit, pp. 1-15.

[4] Ysengrimus, Wikipedia – the free encyclopedia.

[5] “purgatory”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2014. Web. 04 oct.. 2014

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483923/purgatory>.

[6] “A. A. Milne”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2014. Web. 05 oct.. 2014 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/383024/AA-Milne>.

27 Friday Jan 2012

Posted in Art, French-Canadian Literature

Tags

Battle of the Plains of Abraham, Champlain, classification, Curé Labelle, farming, French-Canadian literature, Henri-Raymond Casgrain, Maria Chapdelaine, roman du terroir

Classification of Canadian Literature in French

Until recently, Canadian Literature in French was divided into four periods. This has changed.

A few years ago, the period of French-Canadian literature during which l’abbé Casgrain’s books were published was called la “Patrie littéraire” or the “Literary Homeland” and it took us from 1760 (the battle of the Plains of Abraham)[i] to 1895.

That period is still called the “Literary Homeland,” but it begins in 1837 and ends in 1865. It has been shortened by seventy-seven (77) years now labelled “Canadian Origins” (1760-1836).

Henri-Raymond Casgrain‘s Pèlerinage au pays d’Évangéline was published in 1855. It was therefore written eleven years before the start of the next period currentled called: “Messianic Survival” (1866-1895). However, Un Pèlerinage au pays d’Évangéline does underline the importance of the priest as leader in the organisation of a territory, in our case, Acadie under l’abbé Sigogne and other French émigrés priests sent by England to the seminary in Quebec city (Lower Canana).

As for Maria Chapdelaine, it is now classified in a period of French-Canadian literature called “Exile and the Establishment of Roots (1896-1938).” Where Maria Chapdelaine (1916) is concerned this classification is accurate, but only to the extent that classifications can be correct. Formerly it was included in a period called: “Vaisseau d’or [the title of a poem] et Croix du chemin [road side crosses]” (1895-1938)

What may be good to remember about Maria Chapdelaine is

Not that Maria is a nationalist. The poor girl would not know anything about nationalism or any “ism,” but she nevertheless makes the patriotic choice in deciding to marry a settler. Colonisation was a way of keeping French Canadians in their province, in their parish, and farming.

Priests feared that once a French Canadian settled in the United States, he and members of his family would cease to be good Catholics and would no longer speak French. In all likelihood, this is what motivated the colourful Curé Labelle (November 24, 1833 – January 4, 1891) to urge people to go north and to create land: faire de la terre, faire du pays.

—ooo—

New France: farming as a priority

I should note moreover that even in the earliest days of New France, France saw its colony as a colony of farmers. Pierre Dugua de Mons or Champlain had managed to convince Henri IV, le bon roi Henri, to move the colony from Port-Royal in Acadie (in the current Nova Scotia) to what is now the province of Quebec. As well, Champlain explored the great lakes. Moreover, he engaged in fur trading, but Louis XIII, no doubt acting on the advice of Richelieu and Marie de Médicis, Henri IV’s widow, ordered Champlain to stop exploring and to govern instead. So Champlain was Governor of New France and New France was a nation of farmers.

In short, Maria Chapdelaine, 1916, is a “roman du terroir,” a regionalist novel, extolling the virtues of farming. There would be other such novels, the last of which was published in 1938: Ringuet’s Trente Arpents.

Conclusion

So far, we have examined works belonging to two periods of Canadian Literature in French:

1. The Literary Homeland or Patrie Littéraire (1837-1865): Un pèlerinage au pays d’Évangéline (1855) and

2. Exile and the Establishment of Roots (1896-1938): Maria Chapdelaine, 1913. During this period French-speaking Canadians were either leaving Canada or settling in new areas, the North mainly. For instance some sons became voyageurs. The family farm could no longer be divided, so they had to find other means of making a living. Yet farming remained the mission of French-speaking Canadians and his only means of earning a living.

3. But, I have also touched on a third period: The Messianic Survival (1866-1895). Priests are organizing a new Acadie.

But, for the time being, our plate is full. We pause. I am including an Ave Maria because as Maria Chapdelaine senses her François is in danger, she recites a thousand Ave Marias.

This is not a new post, but it is a clearer one. I cannot presume you already knew about the mythic, yet very real Évangéline, or Maria Chapdelaine.

________________________

[i] The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, 1759, opposed the French, under the Marquis de Montcalm and the English, under General Wolfe. The English won and four years later, in 1763, Nouvelle-France became a British colony.

© Micheline Walker 27 January 2012 WordPress

The fables listed below are not necessarily an analysis of a fable by Jean de La Fontaine (1621 – 1695). A few have been used to reflect current events.

I usually list or quote the Æsopic equivalent of a fable by La Fontaine. If so, I use the Perry Index classification, a number, of the corresponding Æsopic fable. There are many versions of Æsopic fables as they have been rewritten by several authors. Marie de France (12th century [Anglo-Norman]), Walter of England (12th century [Anglo-Norman]) and Jean de La Fontaine (17th century [French]) wrote Æsopic fables, but Jean de La Fontaine made Æsop’s fables La Fontaine’s fables.

If one is looking for versions of a fable, one’s best guide is Laura Gibbs’ Bestiaria Latina (mythfoklore.net/aesopica). I have written posts on several fables and examined elements such as how mythological animals differ from mythical animals and have named the genres in which animals are featured. See Anthropomorphism and Zoomorphism.)

A

B

The Bear and the Gardener, “L’Ours et l’amateur des jardins”

C

The Cat’s Only Trick, “Le Chat et le Renard” (IX.14) (The Cat and the Fox) (10 May 2013)

The Cat Metamorphosed into a Maid, by Jean de La Fontaine, “La Chatte métamorphosée en femme” (II.18) (20 July 2013)

“Le Chêne et le Roseau” (The Oak and the Reed): the Moral (I.22) (28 September 2013)

The Cock and the Pearl, La Fontaine cont’d (I.20), “Le Coq et la Perle” (I.20) (10 October 2013)

D

F

La Fontaine’s “The Fox and the Grapes,” “Le Renard et les Raisins” (III.11) (23 September 2013)

The Fox & Crane, or Stork, “Le Renard et la Cigogne” (I.18) (30 May 2013)

The Fox & Crane, or Stork (I.18) (30 September 2014)

The Frogs Who Desired a King, a Fable for our Times, “Les Grenouilles qui demandent un roi,”(III, 4) (12 November 2016)

The Frogs Who Desired a King (III.4) (18 August 2011)

G

H

The Hen with the Golden Eggs, “La Poule aux œufs d’or” (V.8) (1 June 2013)

“…the humble pay the cost” (II.4), “Les Deux Taureaux et une Grenouille,” The Two Bulls and the Frog (II.4) (29 September 2015)

M

The Man and the Snake, “L’Homme et la Couleuvre” (X.1) (9 November 2011)

The Miller, his Son, and the Donkey, quite a Tale, “Le Meunier, son fils et l’âne” (III.1) (16 May 2013)

A Motif: Getting Stuck in a Hole, “La Belette entrée dans un grenier,” (III.17) (16 April 2013)

Another Motif: The Tail-Fisher, “Le Renard ayant la queue coupée” (V.5) (20 April 2013)

The Mouse Metamorphosed into a Maid, by Jean de La Fontaine, “La Souris métamorphosée en fille” (II.18) (30 July 2013)

N

The North Wind and the Sun, “Phébus et Borée” (VI.3) (16 April 2013)

O

The Oak Tree and the Reed ,“Le Chêne et le Roseau,” (I.22) (28 September 2013)

“Le Chêne et le Roseau” (The Oak and the Reed): the Moral (I.22) (28 September 2013)

P

The North Wind and the Sun, “Phébus et Borée” (VI.3) (16 April 2013)

T

Fables and Parables: the Ineffable (The Two Doves, “Les Deux Pigeons”) (12 June 2018)

The Two Doves, “Les Deux Pigeons” (IX.2) (24 May 2018)

“…the humble pay the cost” (II.4), “Les Deux Taureaux et une Grenouille,” The Two Bulls and the Frog (II.4) (29 September 2015)

The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse, “Le Rat de ville et le Rat des champs” (I.9) (18 August 2013)

The Two Rats, the Fox and Egg: The Soul of Animals, “Les Deux Rats, le Renard, et l’Œuf” (IX. last fable) (15 May 2013)

Y

You can’t please everyone: Æsop retold, “Le Meunier, son fils, et l’âne” (X.1) (21 March 2012)

Theory

Fables and Parables: the Ineffable (The Two Doves, “Les Deux Pigeons”) (12 June 2018)

Fables: varia (12 March 2017)

Anthropomorphism and Zoomorphism (6 March 2017)

To Inform or Delight (29 March 2013)

Texts and Classification

La Fontaine’s Fables Compiled & Walter Crane (25 September 2013)

Musée Jean de La Fontaine, Site officiel (complete fables FR/EN)

Perry Index (classification of Æsop’s Fables)

La Fontaine & Æsop: Internet Resources

Aarne-Thompson-Uther (classification of folk tales)

I’m working on doves and roses as symbols.

Love to everyone ♥

Gustave Doré

© Micheline Walker

15 June 2018

WordPress