Tags

Aberdeen Bestiary, Ashmole Bestiary, Bestiary, Marischal College, Royal Librarian, Thomas Reid, Westminster Palace

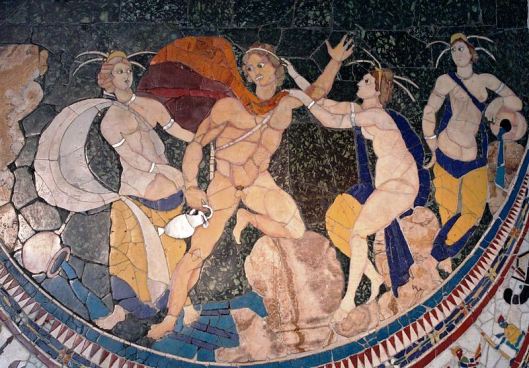

The Unicorn (F15r) the Aberdeen Bestiary

The Unicorn (F15r) the Aberdeen Bestiary

Folio: a page; 4: page number; v: verso as opposed to r: recto

Online Manuscript: http://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/translat/1r.hti Index of Animals: http://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/contents.hti Photo credit: http://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/translat/1r.hti the Aberdeen Bestiary, Wikipedia the Bestiary.ca: http://bestiary.ca/- The Aberdeen Bestiary is housed in the Aberdeen University Library, Univ Lib. MS 24

- It is a 12th-century English illuminated manuscript, as is The Ashmole Bestiary

- It consists of 103 folios measuring , 30.2 cm (height) 21 cm (width)

- It is made of parchment (probably goatskin or sheepskin)

- The calligraphy (not specified), probably littera textualis formata

- The Aberdeen Bestiary includes an illustrated cycle of the Creation

- Codex: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex

Bestiaries

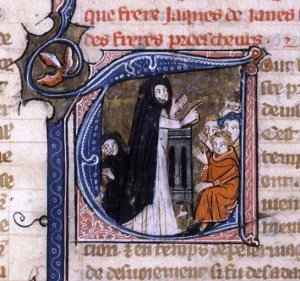

Bestiaries are allegorical illuminated manuscripts in which animals, plants and stones are therefore given a symbolic meaning. Bestiaries differ from Books of Hours and other illuminated manuscripts in that they are not devotional or liturgical in meaning. However, they are moralizing in tone and reflect the ideology of early Christianity. As indicated in Wikipedia’s entry, three days after their death, pelicans give their very blood to bring back to life their dead offsprings, just as Christ rose from the dead three days after his crucifixion, a martyrdom and death he suffered to redeem flawed and sinful humanity.

The meaning of each animal — I am excluding plants and stones — is pre-determined as each possess the attributes given in a

- 2nd-century BCE, a Greek compilation entitled the Physiologus.

Other sources are:

- Rabanus Maurus (c. 780 – 4 February 856) the author of the encyclopaedia De rerum naturis (On the Nature of Things) and De Universo, moralisations added to Isidore’s Etymologies;

- Isidore of Seville (c. 560 – 4 April 636 CE), the author of Etymologiae;

- Saint Ambrose (c. 340 – 4 April 397 CE), a father of the Church and the author of the Hexæmeron, a fourth century commentary on the six days of creation;

- early third-century Gaius Julius Solinus, the author of De mirabilibus mundi also known as the Collectanea rerum memorabilium (‘Collection of Curiosities’), and Polyhistor, a third-century travel guide, incorporating much of Pliny’s Natural History;

- 2nd-century Claudius Aelianus or Aelian, who authored On the Nature of Animals.

Other and older sources are:

- Pliny the Elder, or Gaius Plinius Secundus (23 CE – August 25, 79 CE), the author of a Naturalis Historia; Greek philosopher

- Aristotle (384 BCE – 322 BCE), the author of Historia Animalium;

- Herodotus, the author of Histories, who lived in the fifth century BC (c. 484 – 425 BCE) and is considered the “Father of History.”

Although the treatises of these gentlemen imposed a meaning on animals, they were not necessarily discussing real animals. In fact, among the animals featured in Bestiaries some do not exist or have a poetical reality: the unicorn, the phœnix, the dragon and the griffin are legendary animals and at least two, the unicorn and the dragon are cross-cultural beasts and two of which straddle the mythical and the mythological: the griffin and the phœnix. The others, such as the mythological Centaur, half man, half horse and, therefore, a zoomorphic as well as a mythological animal. In fact, even “real” animals have fantastical attributes. “Real” bears do not lick their cubs into shape.

Christ in Majesty

However, there is a sense in which Christ in Majesty (F4v) belongs to a bestiary. The mythologies I am familiar with all feature Creation tales. Amerindians believed in a Manitou and the Haida Amerindians of the northwest Pacific Coast carve(d) totem poles that suggested animal ancestry, which may point to a belief in evolutionism, except that, as I have already mentioned, Amerindians also had a Manitou (as in Manitoba). These totem poles were at times so beautiful that patrons commissioned Totem poles as Jean de France (30 November 1340 – 15 June 1416) commissioned his Très Riches Heures. (See Totem poles, Wikipedia.)

The Aberdeen Bestiary

The Paper: Parchment, but not vellum (calfskin)

The Aberdeen Bestiary (Aberdeen University Library, Univ Lib. MS 24)[i] is a 12th century English illuminated manuscript bestiary. It was first listed in 1542 in the inventory of the Old Royal Library at the Palace of Westminster in 1542. (See Aberdeen, History.) It was made on parchment (parchemin), which means that the paper used by the artists and scribes was probably sheepskin or goatskin. Although calfskin is called parchment, vellum (calfskin) is the superior parchment, and when vellum is used, the paper is called vellum. This does not lessen the quality of the Aberdeen Bestiary.

From the Old Royal Library to the Aberdeen University, via Thomas Reid

The history of the illuminated manuscript is somewhat mysterious. According to scholars and researchers involved in the Aberdeen Project, the manuscript was listed as No 518 Liber de bestiarum natura in the inventory of the Old Royal Library, at Westminster Palace (1542). This library was assembled by Henry VIII (28 June 1491 – 28 January 1547), with the assistance of antiquary John Leland, to house manuscripts and documents rescued from the dissolution of the monasteries. However, the manuscript may have been part of the royal collection. Many books “escaped” from the Royal Library. (See Aberdeen, History.)

The Aberdeen Bestiary was probably given to Thomas Reid[ii] by Patrick Young, the son of Royal Librarian, Sir Peter Young. Thomas Reid was Regent of Marischal College, Aberdeen and Latin Secretary to James VI. As for Thomas Reid, he gave the precious illuminated manuscript, along with about 1350 books and manuscripts, to Marischal College in 1624-1625. In the 1720s, the books of Marischal College Library were reorganised into presses and the Aberdeen Bestiary was catalogued MS M 72, in 1726. When the Library was catalogued by Thomas Gray in c. 1670, the book had the shelfmark 2.B.XV Sc. Excisions were first recorded at that time, but mutilations stopped. “When Marischal College amalgamated with Aberdeen University in 1860, the Bestiary became part of the University collection[,]” which is probably the moment when the Aberdeen Bestiary acquired the shelfmark MS 24. (See Aberdeen Bestiary, Wikipedia.) However, this may not be exact as there is disagreement among scholars. (See Aberdeen, History.)

Sources

Isidori physiologia: Isidore of Seville‘s Etymologiae

When the Library was catalogued by Thomas Gray in c. 1670, the Aberdeen Bestiary was called Isidori physiologia, which suggests that many descriptions of animals were borrowed from Isidore of Seville rather than the compiler of the Physiologus. Isidore of Seville is the author of several books, the most famous of which is the Etymologiae, 184,[iii] “an encyclopedia of all knowledge.” (See Aberdeen, History.)

The Artist or Artists and the Patron

The Artist or artists: The Ashmole or Ashmolean Bestiary

We do not know who illuminated the Aberdeen Bestiary, but experts believe that the miniatures of the Aberdeen Bestiary were painted by the same artist, or artists, as the miniatures that adorn the Ashmole Bestiary. The Ashmole Bestiary[iv] (Bodleian Library [Oxford University] MS. Ashmole 1511) is a late 12th or early 13th century English illuminated manuscript Bestiary containing a creation story and detailed allegorical descriptions of over 100 animals. The anonymous artist probably lived near his patron, in Lincolnshire or Yorkshire.

As for the Patron of MS 24, the Aberdeen Bestiary, he is believed to have been an ecclesiastic on the basis of F32r (turtle doves), F34r (cedars of Lebanon). It seems our patron was Geoffrey Plantagenet, the illegitimate son of King Henry II and therefore half-brother to Kings Richard and John. Geoffrey Plantagenet was Bishop-elect of Lincoln (1173-82) and later Archbishop of York (1189-1212). Moreover, he owned the St Louis Psalter (Leiden U.L. MS 76A), which means he was wealthy. Luxurious illuminated manuscripts were usually commissioned by members of royal families.

Conclusion

When I discovered the Aberdeen Bestiary site, I felt I should perhaps refrain from writing a post on this famous bestiary. A few Aberdeen Bestiary illuminated folios are online. They can be investigated at leisure but images posted on the Bestiary cannot be used without violating copyright legislation. Fortunately Wikipedia has a site containing a good selection of the Aberdeen Wiki Commons.

There was an exceptional interest for animal fables and beast epics beginning with the publication of Nivardus of Ghent’s 1148 or 1149 Ysengrimus. The Ysengrimus (6,574 lines of elegiac couplet) is Reynard the Fox ‘s birthplace. Reynard is called Reinardus and his foe, the wolf, Ysengrimus. In Reynard the Fox, they become Reynard and Isengrim (Renart and Ysengrin [FR]). However, although the animals inhabiting medieval Beast Epics and Fables are anthropomorphic, i.e. humans in disguise, the wolf looks like a wolf and the fox, like a fox.

However, in illuminated Bestiaries not only are animals fanciful, but they are often grotesquely obscene. In fact, when I was a student, the various Reynard the Fox beast epics were not even mentioned in the curriculum. Nor were Bestiaries. If one visits Beverley Minster, in Beverley (Yorkshire), one wonders whether parents should allow their children to see the cathedral’s misericords. I was copiously entertained, but I was also busy looking up members of my husband’s ancestors several of whom have found their final resting place in Beverley Minster.

Bestiaries were commissioned by the wealthy for the wealthy and were not intended for children. Children were probably told children Æsop’s fables as these passed down from generation to generation in an oral rather than learned (written) tradition. In fact, bestiaries circulated in courtly milieux next to the Roman de la Rose, c. 1230, part of which Chaucer translated into English. Let us pause here.

Tiny Gallery

I cannot copy images from the Aberdeen Library site as I would be in violation of copyright laws. But you may see the illuminated manuscripts by clicking on Bestiary.ca. However, images are available at the above-mentioned Aberdeen Wiki Commons, Wikipedia. (Also see the the top of this post.)

- Allegorical Illuminated Manuscripts: Medieval Bestiaries (michelinewalker.com)

- Medieval Bestiaries: the Background (michelinewalker.com)

- The Dragon East & West (michelinewalker.com)

- The Phœnix: on the Importance of Symbols & Myths (michelinewalker.com)

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 26 Feb. 2013

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/496464/Thomas-Reid>. [iii] Etymologiae (ljs184): 184 folios; height: 35.6 cm; width: 24.2 cm, located at the Annenberg Rare Book &

Manuscript Library (University of Pennsylvania), Philadelphia, PA, United States [iv] Ashmole Bestiary, Wikipedia (The Ashmole Bestiary includes an illustrated cycle of the Creation)

- Adam names the Animals (F5r)

- The Unicorn and the Bear (F15r)

- The Dragon and the Elephant (F65v)

- The Lamb (F21r)

- The Female Vulture (F44v)

- The Yale (F16v)

The Yale F16v

© Micheline Walker

21 February 2013

© Micheline Walker

21 February 2013

![Giorgione, Pastoral Concert. Louvre, Paris. A work which the Louvre now attributes to Titian, c. 1509.[9]](https://michelinewalker.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/745px-fiesta_campestre1.jpg?w=529&h=426)