Tags

Anne-Louis Girodet, Atala, Chactas, Chateaubriand, Christianity and the Romantics, Father Aubry, Herb Weidner, les Natchez, René, Simaghan, The Death of Atala, the Noble Savage

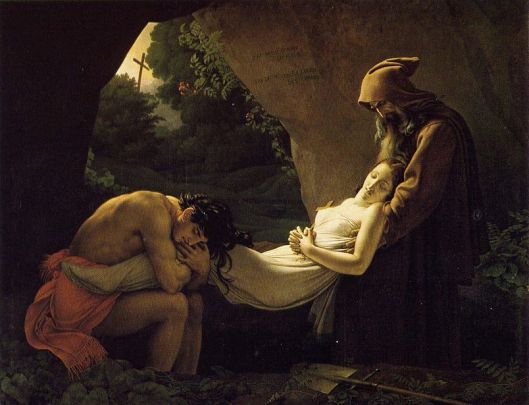

The Funeral of Atala, by Girodet, 1808 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

An “American” novella: Atala (1801)

In 1791, François-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand, an impoverished aristocrat fleeing revolutionary France, travels to America where he spends nine months an lives in Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York and the Hudson valley. Born of this stay in America are Atala, René, Les Natchez and Voyage en Amérique, an EBook.

These works were written in England, as was L’Essai sur les Révolutions. Upon his return to Europe, Chateaubriand joined l’Armée des Princes (the Army of Princes) and, after being wounded in battle, he settled in England where he earned a meagre living teaching French mainly. Despite this painful exile, not only did François-René write the afore-mentioned works, but he also became familiar with English literature and, in particular, with seventeenth-century author John Milton‘s Paradise Lost (1667), a work Chateaubriand would later translate into French. (See Chateaubriand, Wikipedia)

Chateaubriand returned to France in May 1800 when an amnesty was issued émigrés. In 1801, he published Atala, and, the following year, René. Both novellas are incorporated in Le Génie du Christianisme (The Genius of Christianity), a large work published in 1802 and available online. In René, Chateaubriand described “le mal du siècle”[i] or, more precisely, the “vague [from vagueness] des passions,” the form of melancholy experienced by sensitive souls who know they are “fallen gods” (Lamartine, see Le Mal du siècle). Their sorrows bestow superiority on such characters.

“Morbid sadness was mistaken for the suffering of a proud and superior mind.” (See Mal du siècle, Wikipedia.)

Atala, illustrated by Gustave Doré (Photo credit: Project Gutenberg [EBook #44427])

Atala, 1801

Atala, a novella, or short novel, was published in 1801, a year before René. However, although published in 1801, Atala features René, a Frenchman who left France in 1725 and found refuge among the Natchez. The Natchez are a tribe of Amerindians living near the Mississippi and friendly to the French. In Atala, they are near the Ohio River. Chactas could be a “noble savage,” but he is not depicted as such. He is a blind Sachem and a Natchez whose nobility seems to stem from the fact that he is not altogether a “savage.” In a later appearance, Chactas is in France and meets the king.

If Chactas has nobility, which he does, it is mostly because he was brought up by Lopez, the Spaniard who rescued him from the Muscogulges. Lopez also fathered Atala whose mother is a Muscogulge, enemies of the Natchez. Atala’s mother weds the tribe’s magnanimous leader, Simaghan. When Chactas leaves Lopez’ home, he is again captured by the Muscogulges. He is freed by Atala. At this point, le père Aubry, Father Aubry, its fourth (René, Chactas, Atala) and most eloquent character, enters the novella.

F.-René de Chateaubriand, by Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Chactas’ Story

In Atala, Chactas, who has befriended René, tells him his story. After leaving the home of Lopez to rejoin his people, Chactas is captured by Muscogulge Amerindians who quickly prepare to torture and kill him. Kind Atala, a Christian, takes pity on Chactas. She has fallen in love with him and unties him so he can escape torture. The two flee the tribe’s encampment but are caught in a terrible thunderstorm. They then hear the sound of a bell and, suddenly, a dog approaches followed by Father Aubry, a French missionary.

Father Aubry takes Atala and Chactas to his grotto. The priest wants his protégés to wed. However, this prospect saddens Atala profoundly. Atala’s mother made a promise. Her child, Atala, was sick, so she vowed that if Atala survived, Atala would remain a virgin. On her deathbed, Atala’s mother extracted the same promise from Atala herself. Atala does not tell Chactas and father Aubry about her vow of chastity.

While Father Aubry and Chactas are visiting the mission, Atala takes poison. On their return, Chactas and father Aubry find Atala lying down, in agony. She tells her story and Father Aubry quickly explains that the oath she has made to her dying mother can be undone. But it is too late.

Ô ma mère ! pourquoi parlâtes-vous ainsi ! Ô religion qui fais (sic) à la fois mes maux et ma félicité, qui me perds et qui me consoles ! (pp. 52-53)[ii]

(O my mother, why spake you thus? O Religion, the cause of my ills and of my felicity, my ruin and my consolation at the same time!) (“Félicité,” felicity) means “bonheur” (happiness).

Ambivalence towards Christianity is expressed. A grief-stricken Chactas is indignant and, after rolling on the ground in Amerindian fashion, he says: “Homme prêtre, qu’es-tu venu faire dans ces forêts ?” (Man-priest, why did you come into these forests?). “To save you,” replies the old man who shows considerable anger defending Christianity and then absolves Atala of her suicide. It is not a sin, because she did not know her suicide was a transgression. She is “ignorant.”

“[A]ll your misfortunes are the result of your ignorance. Your savage education and the want of instruction have been your ruin. You did not know that a Christian cannot dispose of his life.”

We then witness Atala’s agony, together with Chactas and le père Aubry. Atala dies but is buried discreetly at the “Groves of Death.” Later, Father Aubry dies when his mission is attacked by Cherokee Amerindians who torture him to death. He will be buried near Atala, and René will come to collect the bones of both Atala and Father Aubry.

Chateaubriand’s Savage: not so Noble

Note that le père Aubry is a white man and that “everything about him was calm and sublime.” Chactas was brought up by Lopez, a Spaniard and a Christian. Moreover, Lopez is Atala’s father. As for René, to whom Chactas told his story, he is a French émigré who moved to Louisiana in 1725. It would appear, therefore, that Atala’s savages are not altogether “savages.”

Atala was “proud” of her Spanish blood and “resembled a queen in the pride of her demeanor, disdained to speak to these warriors.” Until she met Chactas, she felt those “warriors” who surrounded her were not worthy of her. Je n’aperçus autour de moi que des hommes indignes de recevoir ma main; je m’applaudis de n’avoir d’autre époux que le Dieu de ma mère. (p. 53) (I saw myself surrounded by men unworthy of receiving my hand; I congratulated myself upon having no other spouse than the God of my mother.) Obviously, the natives Atala knows seem inferior to Europeans. Yet, the Natchez are René’s refuge. Could this be the case if Chateaubriand considered them irredeemably uncivilized?

Alfred de Musset

Atala is a bittersweet chapter in the tale of the “Noble Savage.” Chateaubriand’s savage is not a noble savage, at least not consistently. In particular, he is extremely cruel. Savages, Iroquois, allies of the British, tortured and burned alive Jesuit missionary Jean de Brébeuf and other missionaries, in 1625. But Chateaubriand is among émigrés who escaped the savage Reign of Terror: 1793. Robespierre and company were barbarians.

However, the setting confers a degree of exoticism to Atala and it allows Chateaubriand feats of style. The Amerindians bring food to our Europeans and Chactas is dressed in bark, etc. It’s called “couleur locale” and it is all the more colourful since Chateaubriand was not closely acquainted with Amerindians.

It is difficult not to agree with Alfred de Musset that “[t]he entire malady of the present century stems from two causes: the nation that lived through 93 [la terreur or the reign of terror] and 1814 [Napoleon’s defeat: the Battle of Paris] had its heart wounded twice. All there was is no longer; all that will be has yet to come. Seek nowhere else the secret of our ills.” (See Musset’s Confession of a Child of the Century, Preface by Henri Bornier of the French Academy, Project Gutengerg [EBook #3942].

At any rate, as she is dying, Father Aubry tells Atala that life is a painful journey. “Remerciez donc la bonté divine, ma chère fille, qui vous retire si vite de cette vallée de misère.” (p. 52) “Thank, therefore, the Divine goodness, my dear daughter, for taking you away thus early from this valley of misery.”[iii]

Indeed, a “valley of misery” it is for René who lives in exile, as do all émigrés and will those Natchez, the Amerindians who had adopted René and have survived the destruction of their encampment, Father Aubry’s mission. They are leaving, carrying the bones of their ancestors. Leading the cortège are the warriors, and closing it, women carrying their newborn. In the middle are the older Natchez. There is nobility to these “savages.”

“O what tears are shed when we thus abandon our native land!—when, from the summit of the mountain of exile, we look for the last time upon the roof beneath which we were bred, and see the hut-stream still flowing sadly through the solitary fields surrounding our birth-place!”

Oh ! que de larmes sont répandues lorsqu’on abandonne la terre natale, lorsque du haut de la colline de l’exil on découvre pour la dernière fois le toit où l’on fut nourri et le fleuve de la cabane qui continue à couler tristement à travers les champs de la patrie.” (p. 73)

—ooo—

The final paragraph of Atala is very revealing, and on these words, I will end this post.

“Unfortunate Indians!—you whom I have seen wandering in the deserts of the New World with the ashes of your ancestors;—you who gave me hospitality in spite of your misery—I could not now return your generosity, for I am wandering, like you, at the mercy of men; but less fortunate than you in my exile, I have not brought with me the bones of my fathers.”

Indiens infortunés que j’ai vus errer dans les déserts du Nouveau-Monde avec les cendres de vos aïeux ! vous qui m’aviez donné l’hospitalité malgré votre misère ! je ne pourrais vous la rendre aujourd’hui, car j’erre, ainsi que vous, à la merci des hommes, et moins heureux dans mon exil, je n’ai point emporté les os de mes pères !

RELATED ARTICLES

- The Jesuit Relations: an Invaluable Legacy, revisited (22 May 2015)

- Chateaubriand’s Atala (24 April 2015)

- Le Mal du siècle: 19th-Century (18 April 2014)

- The Nineteenth Century in France (5 March 2014)

- The Noble Savage: Lahontan’s Adario (26 October 2012)←

Sources and Resources

Chateaubriand Atala FR is an online publication Wikimedia Commons FR Atala EN is Project Gutenberg publication [EBook #44427] EN, illustrations by Gustave Doré René EN & Complete Works The Genius of Christianity EN Les Martyrs FR, illustrations by Jean Hillemacher Mémoires d’outre-tombe EN Tome I is Project Gutenberg publication [EBook #18864] Tome II is Project Gutenberg publication [EBook #23654] See Internet Archives Alfred de Musset Confession of a Child of the Century EN is Project Gutenberg publication [EBook #3942] ____________________[i] The term mal du siècle was coined by Alfred de Musset. Chateaubriand uses the words vague des passions.

[ii] François-René de Chateaubriand, Atala, René, Le Dernier Abencérage, Les Natchez (Paris: Librairie Garnier Frères, n.d.), pp. 52-53. (a very old edition)

[iii] François de Malherbe (1555 – 16 October 1628), Consolation [Lament] à Monsieur du Périer sur la mort de sa fille. (See Consolation). Malherbe expressed a related thought in Consolation à Monsieur du Périer. This is an instance of intertextualité.

Herb Weidner (composer)— Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, self-portrait (1824), drawing in pencil and Conté crayon, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Orléans, France (Photo credit: wikiart.org)

© Micheline Walker 24 April 2014 WordPress

Dear Miicheline,

This is really interesting! Thank you for sharing. I hope you are well!

LikeLike

Thank you Naomi,

The more one looks into this text, the richer it appears.

“Chateaubriand or nothing.” I enjoyed teaching Chateaubriand and rereading the “American” novels was a delight.

I hope you’re well Naomi.

Micheline

LikeLike

This is a wonderful education for me. Beautiful music as always.

LikeLike

Hello!, Just dropping by to tell you that I have nominated you for an award. Check out the nomination here (scroll down the page): http://aquileana.wordpress.com/2014/05/01/greek-mythology-prometheus-the-rebel-titan/

Congratulations and best wishes!!!… Aquileana 😛

LikeLike

How very sweet of you. I scrolled down the page and found it.

Thank you very much,

Take care,

Micheline

LikeLike

It is my pleasure, as you totally deserve it,

Best wishes, Aquileana 😛

LikeLike

Aquileana,

It looks as though I missed this comment. I thank you very much. Your posts are excellent.

Best regards,

Micheline

LikeLike

Enlightened post on Chateaubriand’s book. Very well penned, as always.

Besr regards, Aquileana 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you very much, Aquileana. It’s such an interesting topic.

Best regards, Micheline

LikeLike

Hi, I would like to subscribe for this webpage to obtain latest updates, thus

where can i do it please help out.

LikeLike

Abbie,

One can simply go to michelinewalker.com. The way to subscribe is indicated on the blog. There is a “follow” invitation. But I will check again. Thank you for writing. Best, Micheline

LikeLike