Tags

Aberdeen Bestiary, Ave Phœnice, Évangéline, Job, Lactantius, mythology, myths, pays de Québec, symbols and emblems

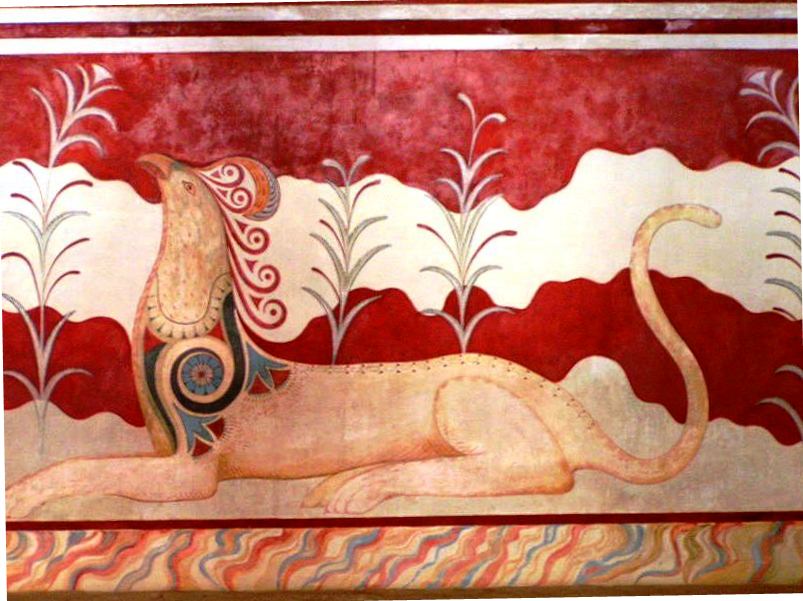

“The Phœnix,” The Aberdeen Bestiary

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)

“The Phœnix,” The Aberdeen Bestiary

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)

If the myth of the phœnix did not exist, we would probably invent it. Mythical creatures are usually born of a human need, which, in this case, is the need for rebirth. Moreover, given that the Phœnix is a transcultural and nearly universal figure, we can presume that the need for rebirth is widely and profoundly rooted in the human imagination.

Our phœnix is the mythical singing bird that is reborn from its ashes. It [le phénix] is associated with a 170 elegiac-verse poem written by Lucius Cæcilius Fiminature Lactantius, an early Christian author (c. 240 – c. 320) and an advisor to the first Christian Roman emperor, Constantine I. The Ave Phœnice is about the death and rebirth of a mythical bird, a bird that rises from its own ashes. This poem was retold in English as The Phœnix, an anonymous Old English poem composed of 677 lines, based on Lactantius’s Ave Phœnice.

Given that the phœnix rises from its ashes, it constitutes a powerful symbol that one can associate with survival, as is the case with Évangéline and Maria Chapdelaine‘s mythic “pays de Québec.” The phœnix is a source of hope to the inhabitants of lands decimated by wars or natural disasters. As a symbol of rebirth, the phœnix also brings hope to those who, like Job, who have lost everything. This is how it appears in the Hebrew Bible:

I thought I would end my days with my family/ And be as long-lived as the phœnix. (Job.29:18) [i]

Mythical and Mythological Animals

Although it appears in the Bible, I am tempted to consider the phœnix as a mythical rather than mythological figure. Mythological figures have ancestors and descendants, or a lineage, which can hardly be the case with the immortal phœnix. However, given that it can rise from its ashes and is therefore immortal and godlike, this distinction may be rather artificial and insignificant. In other words, whether mythical or mythological, the phœnix is a more powerful symbol than the dragon, the unicorn and the griffin, creatures that also lack a lineage, or mostly so.

In beast literature, he is zoomorphic in that he combines features borrowed from many animals, except obviously human features. Remember that Machiavelli’s centaur was half human and half horse. Our phœnix is an animal, albeit legendary.

In Greece, the phœnix (purple) was an “Arabian bird, the only one of its kind, which according to Greek legend lives a certain number of years, at the end of which it makes a nest of spices, sings a melodious dirge, flaps its wings to set fire to the pile, burns itself to ashes and comes forth with new life.”[ii]

The Phoenix (Bestiary.ca)

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica “in ancient Egypt and in Classical antiquity, [the phœnix] was a fabulous bird associated with the worship of the sun. The Egyptian phœnix was said to be as large as an eagle, with brilliant scarlet and gold plumage and a melodious cry.[iii] Besides, it had a life span of no less than 500 years and “[a]s its end approached, the phœnix fashioned a nest of aromatic boughs and spices, set it on fire, and was consumed in the flames. From the pyre miraculously sprang a new phœnix, which, after embalming its father’s ashes in an egg of myrrh, flew with the ashes to Heliopolis (“City of the Sun”) in Egypt, where it deposited them on the altar in the temple of the Egyptian god of the sun, Re.”[iv] The Egyptian phœnix symbolized immortality.

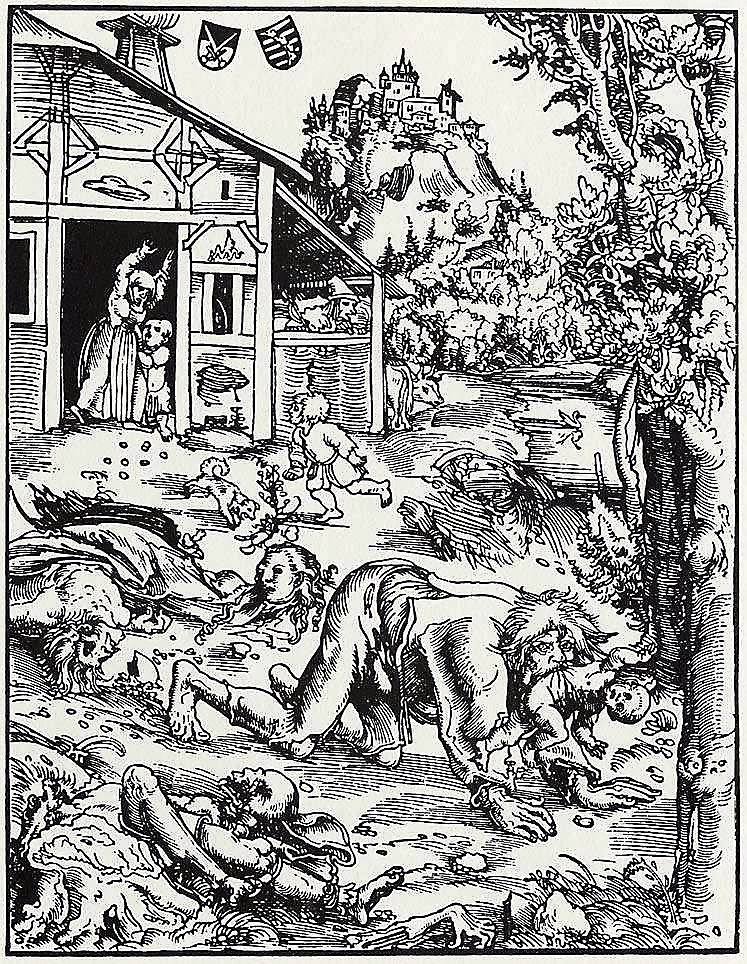

Phoenix depicted in the book of mythological creatures by F. J. Bertuch (1747-1822).

F. J. Bertuch (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

In Islamic mythology the phœnix was identified with the ‘anqā,’ also a bird, but one that “became a plague and was killed.”[v]

Fantasy Literature and elsewhere

The phœnix was used by J. K. Rowling in the fifth book of the Harry Potter series: Harry Potter and the Order of the Phœnix, 2003. It is also featured in Jean de La Fontaine, “Le Corbeau et le Renart,” (Book I.2), or the “Raven and the Fox,” where the Fox tells the crow that because of its beautiful voice, it is a phœnix among the guests of forests: “Vous êtes le phénix des hôtes de ces bois.” In French, blackmail is translated by le chantage. The fox makes the corbeau sing and the cheese drops.

Even the ageless Cinderella narrative has phœnix-like dimensions. The word Cinderella (Cendrillon) is derived from ashes: cinders and cendres. Through the mediation of her fairy godmother, the ash-girl, reduced to that role by jealous sisters and a mean stepmother, a second wife, becomes the princess of fairy tales.

Christian Symbolism

Moreover, we cannot leave aside the phœnix as a Christian symbol. For Christians, the immortal bird represents the resurrection of Christ. On the third day, Jesus of Nazareth rose from the dead as the phœnix rises from his ashes. In the liturgical year, Christians go from Ash Wednesday to the Resurrection: Easter.

Mere Mortals

We cannot escape death as we are mere mortals, but life is nevertheless perpetuated. Outside my window there are naked trees, but they will again be adorned. And even if one’s land is a paper land, a literary homeland, that too is a land. In 1889-1890, Henri-Raymond Casgrain, the author of Pèlerinage au pays d’Évangéline was President of the Royal Society of Canada and quite lucid. Yet there is no “real” Évangéline. She was created by American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, in 1847.

The manner in which humanity copes with its condition often leads to mythification and once the myth is in place, it can be as real and powerful as is Évangéline to Acadians and her “pays de Québec” to Maria Chapdelaine.

[i] Donald Ray Schwartz, Noah’s Ark: an Annotated Encyclopedia of Every Animal Species in the Hebrew Bible (Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson Inc., 2000), p. 400, p. 405, pp. 408-409.

[ii] “phœnix,” in Brewers Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, revised by Adrian Room (London: Cassel House, 2001[1959]).

[iii] “phœnix.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 31 Jan. 2012. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/457189/phoenix>.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

composer: Igor Stravinsky (17 June 1882 – 6 April 1971) piece: “The Firebird” first performed for Sergei Diaghilev‘s Ballets Russes (1910) performers: Vienna Philharmonic (Salzburg Festival, 2000) conductor: Valery Gergiev photograph: Igor Stravinsky

© Micheline Walker

29 May 2014

© Micheline Walker

29 May 2014