Tags

"Mercy Seats", Benedict of Nursia, Benedictine Monasticism, Byzantine Rite, Cenobite Monks, Erimitic Monks, Gargoyles, Gothic, grotesque, Hendrick Vanden Abeele, Kathisma, Misericord, Psallentes

- Choir Stalls at Saint-Pierre Church in Coutances

Stalles de choeur en l’église de Saint-Pierre de Coutances (Photo Credit: Wikipedia)

Choir Stall with a Misericord Beverley Minster, Church of St John, Yorkshire (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Gargoyles

anthropomorphic: humans in disguise or the lion is a king zoomorphic: fantastical creatures blending the features of many animals or combining animal and human characteristic (anthropomorphic, allegorical) allegories (allegorically)If you have seen gargoyles, you are already acquainted with the grotesque (from the Latin: grotto [caves]). Gargoyles (gargouilles) are ingenious drain spouts, or water spouts, built in the shape of grotesque animals. They prevented and still prevent the erosion of exterior walls. Most gargoyles are zoomorphic.

Zoomorphism

Centaurs and the Minotaur Gargoyles the Mermaid the UnicornZoomorphic beings combine the features of several animals, which is the case with the gargoyle shown below. However, they may also combine the features of an animal and those of a human being. In Greek mythology, the Centaur and the Minotaur are both man and beast, as are biblical angels. (See RELATED ARTICLES.)

Anthropomorphism

Reynard the Fox Isengrim the wolf Bruin the bear stereotypesAnthropomorphic animals are humans in disguise. For instance, Reynard the fox and Isengrim the wolf are anthropomorphic animals. They are not zoomorphic animals because they look like a real fox and a real wolf. However, the foxes and wolves of literature and art are all alike in temperament, by “universal popular consent” (George Fyler Townsend). They are stereotypes or archetypes. (See RELATED ARTICLES.)

Zoomorphic & Anthropomorphic

You may find books, articles and internet sites that challenge the above classification, i.e. anthropomorphic versus zoomorphic. My classification is based primarily on the physical attributes of an animal in literature or art. If the animal combines the features of various animals or is both beast and man, that animal is first and foremost zoomorphic. Other considerations are secondary.

Allegorical and Symbolic

As for the denizens of the Medieval Bestiary, the majority, if not all, are allegorical animals, or metaphors. They represent a human attribute, such as a virtue, or a vice, which, strictly speaking, does not make these animals anthropomorphic, or humans in disguise. They are symbols. For instance, the mermaid is the symbol of vanity

Gargoyle, Autun (Photo credit: The Rusty Dagger, BlogSpot)

- The amphisbaena, with the small head seeming to threaten the large one. Misericord; Limerick Cathedral (St. Mary’s), Limerick, Ireland; late 15th century.

- A dragon with four legs and bat wings. Misericord; Cartmel Priory, Cartmel, England; late 14th century.

- Two doves biting at foliage. Misericord (number 30); Exeter Cathedral, Exeter, England; third quarter of 13th century.

- A dragon fights with a lion, while two other dragons watch. This combination is unusual, though the meaning is clear: the lion is Christ, the dragon is Satan, and the lion is winning the fight. Misericord; Carlisle Cathedral, Carlisle, England; early 15th century.[1 & 2]

Miséricordes

monasticism the choir stalls the Canonical Hours sitting while standing kathisma, in the Byzantine riteAs for Misericords (from miséricorde [mercy]), they are ornamented “mercy seats,” narrow wooden seats that fold up when they are not in use. Consequently, the carvings are underneath the seat and hidden when the seat is folded down. It seems they were first used as choir stalls in the quire, by monks living in monasteries and observing the Canonical Hours. Monks who lived in a monastery were called Cenobites. Several monks were recluses and were called eremitical. Others live in a small group.

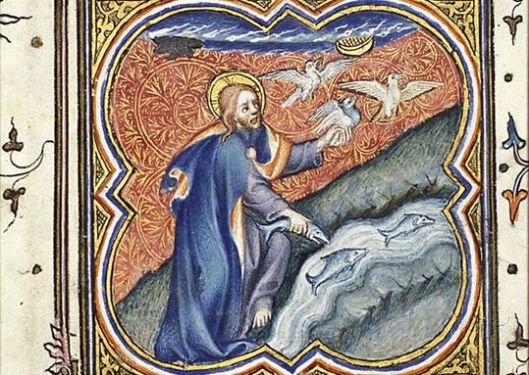

The Benedictine order, or confederation, is 1,500 years old. It was founded by Saint Benedict of Nursia (c. 480 – 543 or 547). Benedictines have therefore sung the eight Canonical Hours, Christian horae, for centuries, which meant standing up for a long time in choir stalls, hence our “misericords,” or mercy seats.

Some monks could survive the ordeal, but many couldn’t. A way of sitting while standing was therefore devised, much to the benefit of church architecture and art. (See Misericord, Wikipedia.) In the Byzantine rite, Eastern monasticism, a misericord is called a kathisma, literally a seat, but it is not as ornate as misericords. In the Western Church, cathedra also means a seat. Cathedrals are the seat of a bishop. Interestingly, Eastern monasticism precedes Western monasticism.

In Western monasticism, monks have used Gregorian chant, a plainchant (unison), as opposed to polyphonic compositions. Gregorian music was developed by Saint Ambrose (c. 340 – 4 April 397) and, to a larger extent, by Saint Gregory or Pope Gregory I (c. 540 – 12 March 604).

Benedict of Nursia wrote the Rule of Benedict, a text which many consider foundational to monasticism in general. The Rule of Benedict is observed by other monastic orders as is the Rule of St. Augustine, written by Augustine of Hippo (13 November 354 – 28 August 430).

I saw several misericords at Beverley Minster, in the Yorkshire. Ironically, Beverley Minster is the church where a large number of my husband’s ancestors have been laid to rest. I also saw several misericords in the “cathedral” at Coutances, in lower Normandy, where we lived for nearly a year. Many of Beverley Minster’s misericords are sexually explicit and some, quite repulsive. One does not expect to see such carvings in a church or a cathedral.

The Mermaid, a symbol of vanity, Église Notre-Dame, Les Andelys, Eure (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Camel (?) Sant’ Orso, Italy (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Reynard the Fox

Misericords often featured animals from Le Roman de Renart (Reynard the Fox). I have seen pictures of these, but Reynard misericords and misericords on fox lore require their own post.[3]

A Revival of the Grotesque & the Gothic

Both gargoyles and misericords, gargoyles mainly, are architectural and functional elements, but ornamented. They do, however, revisit our standard or “classical” view of beauty. There was a revival of the grotesque in 19th-century France and elsewhere. Romanticism was, to a large extent, a rejection of the classicism of the 17th and 18th centuries, considered a foreign element.

The grotesque and the Gothic (fiction, architecture, and the Gothic revival) are related to one another. Victor Hugo‘s 1831 Hunchback of Notre-Dame (Notre-Dame de Paris) is one of the foremost literary examples of this blend. Notre-Dame de Paris will be discussed in a future post.

St. Benedict delivering his rule to the monks of his order, Monastery of St. Gilles, Nîmes, France, 1129 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Conclusion

Misericords were used from the 13th century to the 17th century, but the later ones, those carved in the 17th century, were often copies of earlier misericords. Elaine C. Block writes that:

“[a]t the dawn of the Renaissance, tens of thousands of medieval misericord carvings must have existed. Since then only about ten thousand historiated carvings remain.”[4]

Many were destroyed with the rise of Protestantism and through acts of vandalism. There are modern misericords, but they are not included in G. L. Remnant‘s 1969 catalogue, reissued in 1998.[5]

They are a collector’s item and most are beautifully carved. The Coutances choir stalls, shown at the top of this page, also feature the endless knot motif, a characteristic of Celtic art.

With my kindest greetings to all of you.

RELATED ARTICLES

- The Fox, by “Universal Popular Consent” (25 September 2014)

- Anthropomorphism and Zoomorphism (25 August 2013)

- Canonical Hours or the Divine Office (18 November 2011)

Sources

- Wood Carvings in English Churches [EBook #43530]

- Notre-Dame de Paris is a Project Gutenberg publication [EBook #2610] EN

- Notre-Dame de Paris is a Project Gutenberg publication [EBook #19657] FR

- Rule of Saint Benedict (oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2202) (EN)

- La Règle de Saint Benoît (FR)

- La Regla de San Benito (SP)

____________________

[1] Francis Bond, Wood Carvings in English Churches (Oxford University Press, 1910). [EBook #43530]

[2] David Badke, The Medieval Bestiary (Caption and Photo credit)

[3] Elaine C. Block and Kennett Varty, “Choir-Stall Carvings of Reynard and other Foxes” in Kenneth Varty, ed. Reynard the Fox: Social Engagement and Cultural Metamorphoses in the Beast Epic from the Middle Ages to the Present (Oxford & New York: Berghahn Books, 2000), pp. 125-163.

[4] Op. cit., p. 125.

[5] G. L. Remnant, Misericords in Great Britain; with an essay on their iconography by Mary D. Anderson. (Oxford University Press, 1998 [1969]).

O Sancta Mater Begga (Gregorian Chant by Chant Group Psallentes, directed by Hendrik Vanden Abeele)

© Micheline Walker 8 November 2014 WordPress