Tags

Æsop, Gabriele Faerno, Giovanni Maria Verdizotti, La Fontaine, Nazreddine et son fils, Perry Index, Tales of Count Lucanor

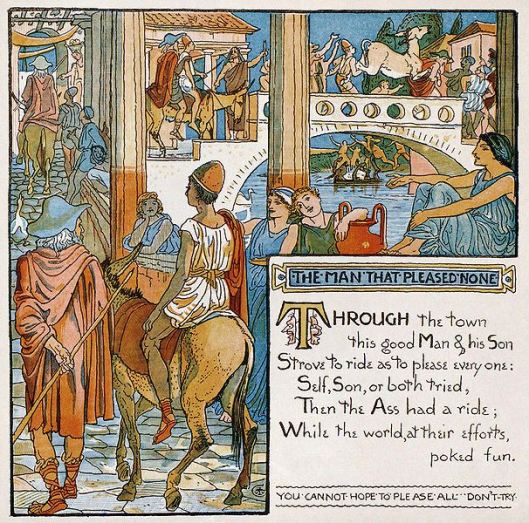

Walter Crane‘s composite illustration of all the events in the tale for the limerick retelling of the fables, Baby’s Own Æsop.

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Le Meunier, son fils et l’âne FR

The Miller, his Son and the Ass EN

I have revised a post published in 2012. The pictures are now clearer. To view the post, simply click on the following link (the first link):

- You can’t please everyone, Æsop retold (michelinewalker.com)[i]

- The Man, the Boy, and the Donkey (classification)

- The Man, the Boy, and the Donkey (text)

In the Aarne-Thompson classification index, The Miller, his Son and the Donkey is motif 1215 and bears many names. For the time being, we will call it The Man, the Boy, and the Donkey.[ii] By clicking on this title, we will see tales related to AT 1215.

I used La Fontaine’s version of this fable, entitled Le Meunier, son fils, et l’âne FR, but it is also an Æsopic fable The Miller, his Son and the Donkey, Perry Index 721, AT 1205 (English). Given that Greek playwright Aristophane‘s (450 BC) alluded to our story in The Frogs; given, moreover, that it also belongs to the Æsopic corpus, The Miller, his Son and the Donkey is a very old fable. However, it would appear La Fontaine used as immediate model, a Racan retelling and the last fable in a collection of fables by Gabriele Faerno (1510 [Cremona], 17 November 1561 [Rome]), entitled Centum fabulae (A Hundred Fables). The moral of Faërne’s (FR) fable is that, if one tries to please everyone, one pleases very few individuals, or none at all.

Wikipedia’s The Miller, his Son and the Donkey

Nasreddin and other retellers

According to Wikipedia, La Fontaine was also influenced by Poggio Bracciolini,[iii] called Poggio (11 February 1380 – 30 October 1459), who included the story in his Facetiæ (1450). It is the opening poem of Giovanni Maria Verdizotti‘s Cento favole morali (1570) (One Hundred Moral Tales). However, “[t]he oldest documented occurrence of the actual story is in the work of the historian, geographer and poet Ibn Said (1213-1286), born and educated in Al-Andalus[,]” in Islamic Iberia, now Spain and Portugal. The story is also told in the Forty Vezirs, translated from Arabic into Turkish by Sheykh Zada. It is one of the stories told in the Arab world’s Goha.

The story was also written in the 17th century by Ottoman Turkish Nasreddin, who, according to Wikipedia, “dealt in concepts that have a certain timelessness” (Wikipedia). His advice to his son (son fils) is:

“If you ever should come into the possession of a donkey, never trim its tail in the presence of other people. Some will say that you have cut off too much, and others that you have cut off too little. If you want to please everyone, in the end your donkey will have no tail at all.” (Nasreddin Hodja)

Photo credit: Google Images

In the 13th century, Jacques de Vitry translated the tale and inserted it in his Tabula exemplorum.[iv] It was also translated by Juan Manuel, Prince of Villena (5 May 1282 – 13 June 1348). The story, entitled “What happened to a good Man and his Son, leading a beast to market,” is included in the Tales of Count Lucanor (1335). It can be found in Shakespeare’s Jest Book (c. 1530), in German meistersinger Hans Sachs, who created it as a broadsheet, in 1531. It is also part of German author Joachim Camerarius‘ Asinus Vulgi. This version was used by the Dane Niels Heldvad (1563-1634) in his translation of the fable. It was then told by French seventeenth-century Racan, a disciple of French poet Malherbe, who is largely responsible for the development of the poetic rules of French “Classicism.”

We therefore see it in Greece (Aristophanes and Æsop), in the Arab World, in the Ottoman Empire, in Italian city-states, in Spain and Portugal, in England, in Germany and in France.

A 17th-century miniature of Nasreddin, currently in the Topkapi Palace* Museum Library. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

*Topkapi Palace (Istanbul, Turkey) was the primary residence of the Ottoman Sultans for approximately 400 years (1465-1856) of their 624-year reign. (See Topkapi Palace, Wikipedia and Nasreddin, Wikipedia.)[v]

Conclusion

The miller, his son and the donkey is an old story. In all likelihood, it dates back to Æsop, if there ever lived a Æsop. If so he was a reteller. In the case of La Fontaine’s Le Meunier, son fils et l’âne, we know his immediate sources: Racan and Gabriele Faerno.

In my earlier post, I point to a moral underlying the moral. The people who give advice to the miller and his son are judgmental. But the fable could also be linked to analysis paralysis. We often need to seek advice, professional advice in particularly, but we can’t let others stifle our inner voices. I believe that instinct is often one’s best guide. When in doubt, abstain! (Dans le doute, abstiens-toi.)

I will close by noting, first, that The miller, his son and the donkey is an example of shared wisdom: the Greeks, Islamic Iberia, the Arab world, Ottoman Turks and various European cultures. Second, tales we call “folktales” have a wide range of listeners, readers and writers. Not only are stories delightful, but they also override rank and constitute a testimonial to pluralism.

______________________________

[i] https://michelinewalker.com/2012/03/21/you-cant-please-everyone-aesop-retold/ [ii] Poggio discovered the only manuscript of Lucretius‘s De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things). [iii] http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/type1215.html (classification) [iv] See Exemplum, Wikipedia [v] “Ottoman Empire”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 16 May. 2013 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/434996/Ottoman-Empire/44376/Restoration-of-the-Ottoman-Empire-1402-81>. Ottoman Turkish Music from 17th century Nikriz Peşrev by Ali Ufki Bey © Micheline Walker

16 May 2013

WordPress

Nasreddin

© Micheline Walker

16 May 2013

WordPress

Nasreddin