Tags

C. S. Lewis, fantasy, Harry Potter, J. R. R. Tolkien, J.K. Rowling, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Lord of the Rings, The Wind in the Willows

Mr Toad jailed because he stole a car. (Photo credit: The Telegraph)

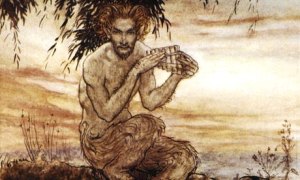

Kenneth Grahame‘s The Wind in the Willows, illustration by Arthur Rackham

Mr Toad jailed because he stole a car. (Photo credit: The Telegraph)

Kenneth Grahame‘s The Wind in the Willows, illustration by Arthur Rackham

NB. This post was published in October 2011. It has been rewritten as the line between the mythical and the mythological is growing thinner.

The Wind in the Willows

(see the video at the bottom of this post)It would appear that animals are indeed everywhere. We find mythological, mythical, zoomorphic and theriomorphic animals in the most ancient texts, but they also inhabit recent literature. Where older texts are concerned, India seems our main source, but mythological and mythical animals are migrants. They travel from culture to culture, and they endure.

In the Bible, we find archangels, good angels, bad angels and Lucifer: the devil himself! As well, the Bible warns that we must not trust appearances. In Matthew 7:15, we read:

Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves.

Literature

Literature is home to an extraordinary number of ravenous wolves. In La Fontaine’s fables, we have a wolf who eats a lamb, “Le Loup et l’Agneau,” and other wolves. In fairy tales, Little Red Riding Hood loses her grandmother to a wolf.

And, as strange as it may seem, literature is also home to the zoomorphic (hybrid) and theriomorphic (deified) animals featured in mythologies, but reappearing along with new fantastic beasts in medieval Bestiaries, including Richard de Fournival’s Bestiaire d’amour, c. 1290.

The Wind in the Willows, by Arthur Rackham

(Photo credit: Encore Editions and Google Images)

The Wind in the Willows, by Arthur Rackham

(Photo credit: Encore Editions and Google Images)

High Fantasy Literature

Finally, literature is home to more or less recent high fantasy works featuring fantastic beasts, many of which are mythical (list of legendary/mythical creatures) or mythological (list of mythological creatures). Certain fantastical beasts are found in medieval bestiaries, where they are considered as “real.”

- J. R. R. Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel (3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) is the author of The Hobbit, 1937, the high fantasy The Lord of the Rings trilogy, written between 1954 to October 1955, and the mythopoeic Silmarillion, published posthumously, in 1977, by Tolkien’s son Christopher and Guy Gavriel Kay. Tolkien taught English literature at Oxford and, among other works, he drew his inspiration from Beowulf for what he called his legendarium.

- C. S. Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963), a friend of Tolkien, is the author of The Chronicles of Narnia, written between 1949 and 1954. Narnia is a fictional place, a realm. Previously, Lewis had published a collection of letters entitled The Screwtape Letters, 1942. Earlier still, Lewis had written his three-volume science-fiction Out of the Silent Planet, a trilogy written between 1938 and 1945 and inhabited by strange figures. C. S. Lewis created Hrossa, Séroni, Pfifltriggi, new creatures who live in outer space, but his cosmology includes angels and archangels. C. S. Lewis’ brother, W. H. Lewis, wrote The Splendid Century, Life in the France of Louis XIV (online), a superior history of seventeenth-century France. He became his brother’s secretary.

- As for J. K. Rowling (b. 1965), she is the author of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, Quidditch Through the Ages (both supplements to the Harry Potter series, 2001), The Tales of Beedle the Bard (supplement to the Harry Potter series, 2008) and the Harry Potter series, which contains several fantastic/al beasts.

Fantastical Beasts and were to Find Them

In these books, written by scholars and well-educated authors, new lands are created as well as new beasts, but these works also feature beasts borrowed from antiquity and various medieval bestiaries, and not necessarily the loftier ones. The books I have mentioned were immensely successful, which shows the importance of fantasy in the human mind. We need imaginary worlds, worlds we cannot navigate without a map, topsy-turvy worlds.

Topsy-Turvy Worlds

What I would like to emphasize is this blog is the topsy-turvy world of beast literature and the comic text. In Reynard the Fox, not only do animals talk, but they are an aristocracy. Humans are mere peasants.

As for the theriomorphic,[i] creatures of mythologies (Pan), briefly mentioned above, they are deified beasts attesting that Beast Literature is indeed an “upside-down” world. Transforming zoomorphic creatures into deities is an inversion of “the natural order of things.” Anthropomorphism presents us with an a world upside-down. With respect to the monk-bishops of the Ysengrimus, Jill Mann writes:

I have said that the Ysengrimus confronts us with a ‘world upside-down’, but in fact the world is turned upside down not once but twice. For the poet sees the real world as already a world-upside-down’. The bishop should be a shepherd to his flock; if he preys on them — acting instead like a wolf — he is inverting the natural order of things.[ii]

The Ysengrimus is the birthplace of Reynard the Fox where the fox is called Reinardus. It is a 6,574-line poem in elegiac couplets, written by Nivardus of Ghent in 1148-49 and translated into English by Jill Mann.

Underworlds, middle-earths, etc.

We also have underworlds. Greek mythology has an Underworld whence one cannot escape, as the three-headed zoomorphic Cerberus guards its entrance.

Tolkien created a “middle-earth” and C. S. Lewis, worlds in outer space. The Judeo-Christian hell is also an underground world. Moreover, how ironic it is that Richard de Fournival should use animals in a courtly love bestiary.

Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows

However my favourite underworld can be found in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908). The Mole and the Rat get lost in the woods during a snow storm. They see a mat and beyond the mat a door that leads to the Badger’s underground residence. After dinner, the Mole, the Rat, the Otter, who arrives later, and Badger, their host, sit by the fire and the Badger praises his underground world where he is sheltered from both the cold and the heat:

The Badger simply beamed on him. ‘That’s exactly what I say,’ he replied. ‘There’s no security, or peace and tranquillity, except underground. And then, if your ideas get larger and you want to expand–why, a dig and a scrape, and there you are! If you feel your house is a bit too big, you stop up a hole or two, and there you are again! No builders, no tradesmen, no remarks passed on you by fellows looking over your wall, and, above all, no WEATHER.[iii]

This statement is very comical, but it is not “innocent.”

Conclusion

I doubt very much that one of my readers will bump into a centaur, or Pan walking down a street. At one level, these are not “real” creatures. However they live in the imagination of a vast number of individuals all over the world. The success of J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series is an eloquent testimonial to the continued need to fantasize and it demonstrates that legendary creatures, mythical or mythological, have survived. Moreover, these creatures, the unicorn and the dragon in particular, are widely known. The unicorn is the Qilin in China. He may be the Hebrew Bible’s Re’em. Be that as it may, they become metaphors: “hungry as a wolf,” “clever as a fox,” and good friends.

In 1909, Theodore Roosevelt, then US president, wrote to Grahame to tell him that he had “read it [The Wind in the Willows] and reread it, and have come to accept the characters as old friends.” (See The Wind in the Willows, Wikipedia)[iv]

The reports of explorers and travellers

Yesterday, I spent several hours looking at Medieval Bestiaries and found the centaur, the griffin, the unicorn, the yale, etc. depicted as “real.” Authors who wrote early natural histories often relied on the reports of travellers to faraway lands who did not have a camera and may not have been good draftsmen. The unicorn could be our rhinoceros. This may be one of the many ways legends grow.

The ‘horned’ shepherd god Pan = panic “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” Kenneth Grahame‘s The Wind in the Willows illustration by Arthur Rackham (Photo credit: The Guardian) ______________________________ [i] “The animal form as a representation of the divine…” Kurt Moritz Artur Goldammer, “religious symbolism and iconography.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 26 Aug. 2013. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/497416/religious-symbolism>. [ii] Jill Mann, “The Satiric Fiction of the Ysengrimus,” in Kenneth Varty, editor, Reynard the Fox: Social Engagement in the Beast Epic from the Middle Ages to the Present (New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2000), p. 11. The Ysengrimus is the birth place of Reynard the Fox where he is called Reinardus. It is a 6,574-line poem in elegiac couplets, written by Nivardus of Ghent in 1149. [iii] The Wind in the Willows is a Project Gutenberg [EBook # 289]. When looking for Project Gutenberg ebooks, it is best to use the Gutenberg link: http://www.gutenberg.org. [iv] “First edition of The Wind in the Willows sells for £32,400”. The Guardian. Retrieved 19 November 2012. Kenneth Grahame’s Mr Toad,

illustration by Ernest Shepard

(Photo credit: James Gurney)

© Micheline Walker

31 October 2011

Revised on 26 August 2013

WordPress

Kenneth Grahame’s Mr Toad,

illustration by Ernest Shepard

(Photo credit: James Gurney)

© Micheline Walker

31 October 2011

Revised on 26 August 2013

WordPress