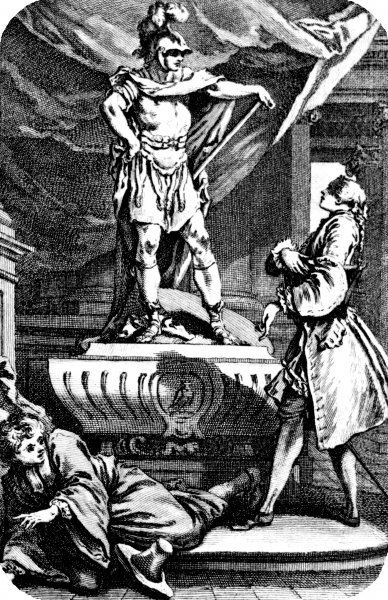

Dom Juan par Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard (commons.wikimedia.org)

Pierrot, Charlotte, Dom Juan et Mathurine (Google)

Don Juan, Zerlina et Donna Elvira par Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard (Google)

My posts on Molière’s Dom Juan overlap. I must apologize. Space is needed when reading Molière’s Dom Juan. There are several layers of meaning. Moreover, Molière’s version of the Don Juan myth differs substantially from other versions.

For instance, we do not see Dom Juan seducing women time and again and marrying them. We see a Dom Juan who has abandoned a loving wife, Elvira. The deal Dom Carlos and Dom Alonse, Elvire’s brothers, propose cannot be faulted. Dom Juan has saved Dom Carlos and met Don Alonse. Both have assessed the problem and are ready to devise a way of restoring their sister’s honour. Dom Juan must return home to his wife. Society has its rules.

Freedom is not a free-for-all, or unlimited. One’s freedom stops where the freedom of others begins. This is the principle that allows human beings to live together in an orderly fashion, or safely. A driver stops at the red light. If he or she doesn’t, the consequences could be devastating. Similarly, love has its rules. André Villiers writes that:

“Love serves in effect as a chopping board for questions regarding the excellence of nature and the freedom of man. Many other developments are possible, but the relations between man and woman, which aliments [feeds] the most incendiary literature, pose in themselves the whole problem of individual freedom and social pressures. The behavior of a man in love points to his inclination and the value he places on it, to the limits he assigns to it and those imposed on him. This is the most pressing of concerns, the one that in the absolute is translated by defeat, and in practice, by all the compromises of everyday morality and the liberties taken in marriage.”[1]

The obligations, stopping at the red light, society has created are not based on religious beliefs.

“The limits imposed on the free exercise of our natural rights are not prejudices or religious beliefs, but the duties ‘necessary for human survival,’ as Locke was to say later on—the rights of Society. There is no other rule of virtue. However, this moral principle is equally valid for the inspiration of a love of humanity.”[2]

In the 17th century, France had yet to enter its “age of enlightenment,” but as peasants became bourgeois, buying offices, they had to devise rules that would allow them to live in freedom, protected, however paradoxical this may seem.

Molière was not harsh on his characters, but he knew there were societal covenants.

“Molière clearly saw the reciprocal relationship between spiritual problems on one side, and social and moral problems on the other. The pretext of a fable [the Dom Juan myth] allowed him to seize the subject in its most vital spot [marriage].”[3]

At no point does Molière admonish his libertin, the womanizer, except through Sganarelle’s words that are nonsense, but true. Womanizing is not freedom, but libertinage érudit was a fruitful meditation on the co-existence of the individual and society, societies that would be increasingly diverse.

Molière was conscious of his obligations. He had to house and feed his comedians and their families. La Grange (who played Dom Juan) kept a registre: earnings, expenses, the fabric and making of costumes, renovations to theaters and the daily life of Molière’s comedians. La Grange entered the troupe in 1659 and, after Molière’s death, he worked on publishing the complete works. That registre kiis a gift to posterity. Molière’s troupe was a “just society.” Molière’s health worried him considerably. There were people who counted on his writing comedies. They made a living as comedians. Having La Grange on board was a blessing.

“Dom Juan is not a dispensation from rules of conduct, nor is it a course in practical morality; but the wealth of ideas that its five acts suggest is considerable. It is a play that offers us ample material for meditation that is not limited to the problem of a particular period, and that leaves us marveling over so unique a work.”[4]

I read, but do not own a copy of Villiers’ Le Dom Juan de Molière, un problème de mise en scène (a problem of staging), 1947. I was in Vancouver, Paris, and Toronto. So, I borrowed books or read them in a library, which is what students do. It is still available. Great!

Beth Adler translated the above, and Jacques Guicharnaud included Villiers’ comments in his Collection of Critical Essays. The chapter madame Adler translated is entitled: L’Essence profonde du drame. In Guicharnaud’s book, the title of this chapter is “Molière Revisited” (pp. 79 – 89).

My favourite words in Villiers’ excerpt are Molière “made a metaphysical shudder go across the stage.” Two and two make four, but there is an unquantifiable dimension to the life of human beings. Sganarelle tells Gusman that he can’t understand why Dom Juan does not believe in the loup-garou (the werewolf) (Act One, Scene One). Molière is incredibly funny, even in farcical tragi-comédies.

In short, Molière’s Dom Juan is about an atheist who abandoned his wife, Done Elvire, was given every opportunity to mend his ways, but seized none. The beggar (le pauvre) is acceptably uncompromising, but Dom Juan isn’t. His behaviour is a transgression of social norms and stems from hubris. The death of the Commandeur may be looked upon as Dom Juan’s original sin. Therefore, when he refuses to return to Done Elvire, the Statue takes his hand and throws him in a fiery abyss. Those who boast… burst.

I could not include André Villiers’ comments in Part Three. Villiers’ chapter is a cogent meditation on Dom Juan.

Dom Juan par François Boucher (dessin) (wikipedia)

You may have noticed that I now make more mistakes than before. Sometimes, I misspell words, and must correct posts after they are published. My posts overlap and I repeat myself. Life inflicted damages. But writing posts on Molière forces me to reread each play very carefully.

I am very grateful to all who read my posts despite delays and some editing.

RELATED ARTICLES

- Reading “Dom Juan” (Part Three) (16 August 2019)

- Reading “Dom Juan” (Part Two) (11 August 2019)

- Reading “Dom Juan” (Part One) (6 August 2019)

- Don Juan: the Cycle & the Traditions (30 July 2019)

Sources and Resources

____________________

[1] André Villiers in Jacques Guicharnaud, Molière, a Collection of Critical Essays (Prentice-Hall, New Jersey, 1964), p. 87.

[2] Guicharnaud, Loc. cit.

[3] Guicharnaud, Op. cit., pp. 86-87.

[4] Guicharnaud, Op. cit., p. 89.

Don Giovanni – Festival di Spoleto – “Don Giovanni a cenar teco…”

The Shipwreck of Don Juan by Eugène Delacroix, 1840 (wikiart.org)

© Micheline Walker

19 August 2019

WordPress

Really interesting

Thank you

LikeLike

Thank you Luisa. Reading Villiers is very stimulating. What is freedom?

LikeLike

Really stimulating…

🦋💙🦋

LikeLike

💟

LikeLiked by 1 person