Tags

Cafés, Chateaubriand, De l'Allemagne, Le Café Procope, Madame de Staël, Romanticism, Salons, Staël theorist, The French Revolution, Victor Hugo

Corbeille de fleurs by Eugène Delacroix (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

“A Basket of Flowers” by Eugène Delacroix (26 April 1798 – 13 August 1863)

The Salon

The world that followed the French Revolution was a new world, but it had kept many of the institutions of the Old World, or l’Ancien Régime. One of these institutions was the salon. The first known French salon was seventeenth-century Catherine de Rambouillet’s Chambre Bleue. Guests enjoyed making believe they were shepherds and shepherdesses and they wrote poems, at times very tricky ones. La Chambre bleue was a magnet. Even Richelieu was inspired to visit.

In the middle of the seventeenth century, Catherine de Rambouillet‘s salon was replaced by Mademoiselle de Scudéry‘s. Mademoiselle de Scudéry was a prolific writer and her favourite subject was love. She drew the map of Tendre, Tendre being the land of love.

In the eighteenth century, the Golden Age of the salon, the most famous was Madame Geoffrin‘s (June 1699 – 6 October 1777). Dignitaries visiting Paris were infinitely grateful for being invited. It was such a privilege, but salons were not as they had been in the seventeenth century. The French eighteenth century was the Age of Enlightenment, so ideas were discussed.

On Monday, Madame Geoffrin received artists and, on Wednesday, men of letters. Ideas were discussed, but never too seriously. That would have been a breach of etiquette. L’honnête homme and the Encyclopédistes were a witty group. All were treated to a fine meal. However, even at Madame Geoffrin‘s salon, love remained a favourite subject.

- Madame Geoffrin‘s salon in 1755 by Anicet Charles Gabriel Lemonnier. Château de Malmaison, Rueil-Malmaison (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

madame Récamier and Chateaubriand

Madame Récamier (4 December 1777 – 11 May 1849)After and even during the French Revolution, except for the “Reign of Terror,” people, gentlemen mainly, flocked to salons such as Madame Récamier’s and Madame de Staël‘s. It is also at that time that François-René de Chateaubriand and Madame de Staël (22 April 1766 – 14 July 1817) inaugurated French Romanticism, a literary movement that gave primacy to sentiment.

Goethe‘s Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werthers) was published in 1774, so France lagged behind both German and English Romanticism. François-René de Chateaubriand would soon publish René and Atala, novellas included in his Génie du christianisme, or Genius of Christianity (1802). It fact, although he is not included in David’s portrait of Madame Récamier, chances are Chateaubriand is looking at the “divine” Madame Récamier. In the early 1800’s, Chateaubriand was the most prominent author in France and Madame Récamier’s finest guest, but as he grew older, he lived like a recluse in a Paris apartment and visited one person only, Madame Récamier, Juliette.

Chateaubriand by Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Germaine de Staël (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

As for Germaine de Staël, a prominent theorist of Romanticism, Napoleon often banished her from France, causing her to spend several years at Coppet, her family’s Swiss residence. She was the French-born daughter of Swiss and Protestant banker James Necker, Louis XVI’s director of finance. Finding a husband for Germaine was not easy. Her father did not want her to marry a Catholic. Although she lived in the company of men who were fascinated by her extraordinary intellectual gifts and charm, most could not be serious candidates because Frenchmen are Catholics. She therefore married baron Erik Magnus Staël von Holstein, a Swedish diplomat.

Victor Hugo & Romanticism

Victor Hugo (26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885)

It could be said that Chateaubriand and Madame de Staël founded French Romanticism, a literary movement that spread to the fine arts and music. She is the author, among several books and treatises, of Delphine (1802) and Corinne (1807), novels. But her most fascinating work is De l’Allemagne, or Germany (1810-1813). It is, to a large extent, a manifesto of Western European Romanticism. She discussed L’Allemagne with her excellent friend and lover, Swiss-born novelist Benjamin Constant, or Henri-Benjamin Constant de Rebecque (25 October 1767 – 8 December 1830), a descendant of Huguenots (French Protestant Calvinists).

However, if French Romanticism has a manifesto, it is Victor Hugo‘s Préface de “Cromwell,” a play published in 1827. The 12-syllable noble verse, called l’alexandrin, had long been broken into two hémistiches of 6 syllables, or “pieds.” Victor Hugo used such alexandrins, but he also divided the 12-syllable verse into 3 groups of 4 syllables or “pieds.”

Je-mar-che-rai//les-yeux-fi-xés//sur-mes-pen-sées, 4 x 3 (3 trimètres) Sans-rien-voir-au de-hors,//sans-en-ten-dr’ au-cun-bruit, 6 x 2 (2 hémistiches)Seul,-in-con-nu,//le-dos-cour-bé,//les-mains-croi-sées, 4 x 3

Trist’,-et-le-jour//pour-moi-se-ra//com-me-la-nuit. 4 x 3 from Hugo’s “Demain, dès l’aube…”

Hugo also brought back things medieval, which he did with Notre-Dame de Paris or The Hunch Back of Notre-Dame. Chateaubriand felt seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French literature was somewhat borrowed, which it was. French authors emulated the Anciens or Greco-Roman literature.

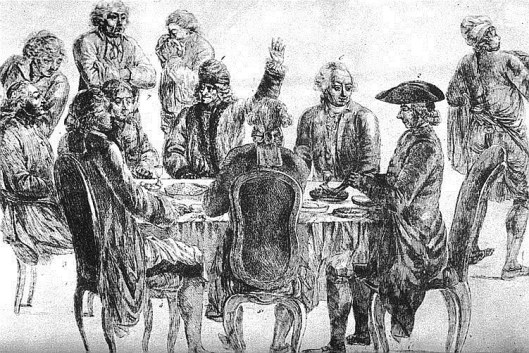

At Café Procope at rear, from left to right: Condorcet, La Harpe, Voltaire (with his arm raised) and Diderot*

*our characters may not be at Café Procope, but they could have been

The Cafés

In cafés, however, men of letters discussed more freely. Cafés had become popular in the seventeenth century. Le Café Procope, established in 1686, has never closed shop except for occasional renovations.

Conclusion

During the French Revolution, Chateaubriand spent 10 years outside France. For one year he was in the United States and then joined an émigré army at Coblenz, Germany. By and large, years émigrés spent abroad were disruptive.

Madame de Staël enjoyed diplomatic immunity in Paris as the wife of Sweden’s ambassador to France. However she lived in England in 1893-1894 with her lover Louis de Narbonne, an émigré. She returned to Paris, via Coppet, her family’s Swiss residence, as soon as the Terreur was over, in the summer of 1794.

She was a successful salonnière under the Directoire (1795-1799), a government toppled by Napoleon’s 18 Brumaire, Year VIII (9 November 1799) coup d’État. She fared poorly under the Consulat, with Napoleon as first Consul. He banished her for nearly a decade but could not prevent her from thinking and writing. Coppet was a beehive. I still enjoy reading Madame de Staël’s De l’Allemagne.

The French Revolution deprived France of tens of thousands of its citizens. But, somehow, tens of thousands survived as did the institutions, salons and cafés, where they congregated to discuss such ideas as liberté, égalité, fraternité.

—ooo—

Sources:- Aurelian Craiutu: Faces of Moderation: Mme de Staël’s Politics during the Directory

- EuropeanHistory.about.com

- The Encyclopædia Britannica

Germaine de Staël (Google images)

Extraordinary women. I wonder what our modern equivalent of a salon might be; something like TED talks?

LikeLike

Dear Gallivanta,

It seems I did not answer this comment. We don’t have salons anymore, but they can be revived on a minor scale.

There are interesting associations. One has to look.

Hugs,

Micheline

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Thanks for the follows « cognitive reflection

Thank you TK. But yours are the best!

Take care,

Micheline

LikeLike

I so enjoyed your post, Micheline! Thank you!! 🙂

LikeLike

Hеy tɦere would you mind shаring which blog platform you’re working with?

I’m looking to start my own blog in thе near future but I’m having a haгd timе choosing between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evоlutіon

and Ɗrupal. Ҭhe reason I ask is because your desigո aոd style

seems ԁifferent then most blogs and I’m looking for somethinǥ

unique. Ρ.S Sorry for getting off-topic but I haԁ to ask!

LikeLike

It took me forever to replay to your comment. Sincere apologies.

Choosing a blogging platform is not easy.

My design is in fact unfinished. I have technical limitations, but WordPress helped.

Take care,

Micheline

LikeLike