Tags

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Franklin Edgerton, Jill Mann, Laura Gibbs, Middle Ages, Panchatantra, playing-dead motif, Reynard, Roman de Renart

Renart and Tiécelin the Crow (BnF, Roman de Renart)

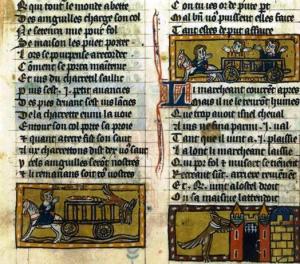

In branch III of the Roman de Renart, the goupil — foxes used to be called goupils — Renart is hungry and goes in search of food. When he gets to the road, he sees a cart loaded with fish and quickly lies across the road making believe he has died. The merchant stops his cart and investigates. He looks at Renart’s magnificent fur and as a merchant he wonders if there isn’t money to be made from the sale of the fur. He throws Renart at the back of the cart, which is precisely what Renart wanted him to do. Our trickster fox therefore feasts on the herrings (les harengs). Having satisfied his hunger, Renart wraps himself into a coat made of eels and jumps off the cart. As he runs away, he shouts “bless you” to the merchant, “there I am with plenty of eels to eat, you can keep the rest!”

Renart et les anguilles (eels) is one of the best known of Renart’s tricks, except that this time he doesn’t take advantage of the wolf Ysengrin (French spelling), the chief character in Nivardus of Ghent’s Ysengrimus (c. 1149). Besides, the fox is not speaking Latin but Roman (le roman).

Renart et les anguilles (the eels) (BnF, Roman de Renart)

The Theft of Fish

Renart et les anguilles (br. III) is classified as motif 1 in the Aarne Thompson (AT) motif index,[i] where it is listed as The theft of fish. The getting-stuck-in-a-hole is motif 50 in the Aarne-Thompson Classification and is called Curing a sick lion. The bear and the honey is motif 49 except that the Roman de Renart’s Brun (Bruin) the bear gets stuck (coincé) in a log and not in a hole.[ii]

the Fox Who Played Dead: Æsop, Abstemius and Renart the Fox

Dr Laura Gibbs[iii] tells us about a fable entitled The Dog and the Fox who Played Dead by Æsop, but based on Abstemius (149). A fox played dead so he could catch birds. The fox “rolled in the mud and stretched out in a field.” However, a dog comes by and mangles the fox, which puts an end to the otherwise deadly ruse.

In the Roman de Renart, the fox entices Tiécelin, the corbeau (the crow), to sing and thus lose the cheese he has stolen. However, before taking the cheese, the fox makes believe he is wounded and when he tries to eat Tiécelin, all he succeeds in grabbing are a few feathers. Both stories are identical except for the presence of a dog in Æsop and Abstemius.

Comments

So, in Æsop the make-believe is stopped by a dog, but the in the Roman de Renart, the make-believe is not carried out to the point of playing dead. However, Tiécelin has a name which suggests that he is a human in disguise, the chief device of animals in literature. In both fables, the fox says he fully deserves to have lost the bird, and the cheese. In Laura Gibbs’ version of The Dog and the Fox who Played Dead, the fox says “This is just what I deserve: while I was trying to catch the birds using my tricks, someone else has caught me.” The same is true of Renart. One has the impression that the fox knows how clever he is and that he can therefore afford to lose.

In the Medieval Bestiary, we read that

“the fox is a crafty and deceitful animal that never runs in a straight line, but only in circles. When it wants to catch birds to eat, the fox rolls in red mud so that it appears to be covered in blood. It then lies apparently lifeless; birds, deceived by the appearance of blood and thinking the fox to be dead, land on it and are immediately devoured.The most famous fox of the Middle Ages was Reynard, the trickster hero of the Romance of Reynard the Fox.”

In fact,

[t]he fox represents the devil, who pretends to be dead to those who retain their worldly ways, and only reveals himself when he has them in his jaws. To those with perfect faith, the devil is truly dead.

Playing dead (faire le mort) is a common ruse illustrated here using two examples from the Roman de Renart and a closely related example from Æsop. If we were to trace back Renart’s ruses, they would take us to the Pañcatantra. The structure of the Roman de Renart is a frame story, stories within a story, which is also the case with the Sanskrit Pañcatantraand its Arabic rendition, Ibn al Muqaffa’s Kalīlah wa-Dimnah.

However, the Roman de Renart is a fabliau. The Pañcatantra and Kalīlah wa-Dimnah do not possess the scurrilous and at times scatological aspect of French fabliaux.[iv] Moreover, if ancient beast epics and fables are used in the education of the prince, it would seem our ancient prince did not live in the albeit comical but ruthless world, the various European countries Reynard the Fox inhabits. We accept his cruel misdeeds because his tricks do not seem to hurt.One is reminded of the comic strips steamroller flattening a cat who always fluffs up again. I am using a comparison taken from Jill Mann[v] in Kenneth Varty,[vi] ed. Introduction, Reynard the Fox: Social Engagement and Cultural Metamorphoses in the Beast Epic from the Middle Ages to the Present (New York & Oxford: Bergham Books, 2000).

Conclusion

The comic text is a “self-redeeming” (the term is mine) by virtue of a powerful convention, the “all’s well that ends well.” But beast epics and fables are also a nītiśāstra. In other words, they are, by vocation and convention, cushioned advice for the “wise” conduct of a prince’s life. According to Franklin Edgerton (1924), “[t]he so-called ‘morals’ of the stories have no bearing on morality; they are unmoral, and often immoral. They glorify shrewdness and practical wisdom, in the affairs of life, and especially of politics, of government.”[vii] As I indicated in an earlier post, Edgerton may be a little severe regarding the morality of the Panchatantra, but, were we to apply his comments to Reynard the Fox, they would not be altogether inappropriate. Renart is a scoundrel.

In closing, I will also point out that the playing-dead motif is particularly important in that playing dead is a real-life option. This particular motif is very much about the “wise” conduct of a prince. For instance, laying low while the country regrouped probably came to the mind of American leaders on 9/11.

Fortunately, when all is said and done, a fox is a fox is a fox.

- Reynard the Fox, the Itinerant (michelinewalker.com)

- “To Inform or Delight” (michelinewalker.com)

- A Motif: Getting Stuck in a Hole (michelinewalker.com)

I read quite a few Reynard stories while developing a storytelling program for a medieval fair, and it is very interesting to see these authentic illustrations and hear the history. Another fine post, Micheline!

LikeLike

Thank you Naomi,

Reynard stories are very popular. In fact, in the last few months many videos on Reynard have become available.

Naomi, I so enjoy your photographs. They will be a fine legacy to the world. You are so talented and you allow us to share in the beauty you capture. It’s marvellous. Thank you.

My kindest regards,

Micheline

LikeLike

http://iamforchange.wordpress.com/awards-page-and-nominations-thank-you-i-am-so-honored-and-grateful/ I wanted to share with you and say thank you!

LikeLike

I thank you for sharing with me and thanking me. Hearing from you was a privilege.

Have a pleasant Sunday.

Best regards,

Micheline

LikeLike

In childhood I have read many stories about the sly fox!

Fox has been and will remain forever all sly.

Thank you so much, dear Micheline your post.

Have a wonderful Sunday and many blessings!

Big hugs, much love, Stefania! 🙂

LikeLike

In literature, the fox is always very cunning. He plays horrible tricks on people, but he remains a favourite because he is so resourceful.

Thank you Stefania.

Big hugs and love,

Micheline

LikeLike

Well, now, that’s uncanny, Michelline. Our walks have been dominated by a dead fox over the last few days; it was just there on the side of the path. Upsetting. Except that today it was there again, in a completely different part of the path. It takes strength to drag things like that around, and our deer don’t go in for it. Reynard has set me thinking….

LikeLike

Beware of that fox. He may be playing dead. The fox is beast literature’s foremost animal.

I hope you are well.

My best,

Micheline

LikeLike