Tags

alazṓn, Dom Juan, Libertinage, Libertine, Miles gloriosus, Senex iratus, Société du Saint-Sacrement, Tartuffe

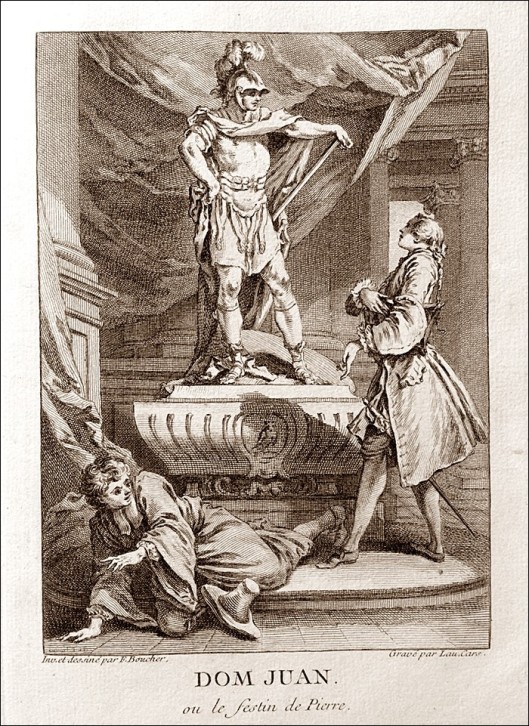

Dom Juan by François Boucher (dessin) & Laurent Cars (gravure) (Google images)

Writing about Dom Juan has been a pleasure. In fact, I received a comment about libertinage in 17th century France.

Le Libertinage

I read René Pintard’s Le Libertinage érudit dans la première moitié du XVIIe siècle when I was writing my thesis, years ago, but I do not own a copy of this book. Wikipedia FR has an entry on the subject and the book is summarized, by GRIHL FR. But obtaining the material one requires to write a book is truly difficult.

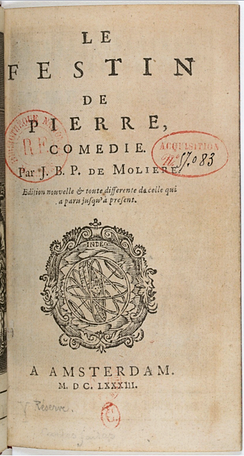

By virtue of his profession, a playwright and an actor, Molière is associated with libertinage érudit. Actors were excommunicated. But libertinage érudit and libertinage are not synonyms. Molière did not lead a dissolute life.[1] However, his Tartuffe (1664) and his Dom Juan (1665) were attacked by la cabale des dévôts. He had to rewrite Tartuffe twice before the play could be performed (1669). As for his Dom Juan, although it was a great success, it closed after 17 performances and was not published until 1682, with passages removed. In 1683, Dom Juan was published in Amsterdam,

La Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement

The most important group of dévots, or faux-dévots, was the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement, Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement, a secret society. Louis XIV himself could not protect Molière fully. Not that impiety went unpunished in Dom Juan, but that devotion is linked to religion and that there were in France genuinely devout persons as well as faux-dévots, persons feigning devotion. Feigned devotion is a powerful mask, and all the more so when it fills the needs of a potentially tyrannical, but frightened pater familias.

It so happens that Orgon needs Tartuffe and is therefore easily blinded by his own needs. He sees what he wishes to see and hears what he wishes to hear. Only Orgon and his mother, Madame Pernelle, see a dévot in Tartuffe. Other members of Orgon’s family can tell that Tartuffe is a hypocrite and a rogue, but they do not have a strong-box, une cassette, containing potentially incriminating evidence. A friend of Orgon was involved in the Fronde and Orgon has his strong-box. So Orgon gives Tartuffe the cassette to breathe easier. However, Tartuffe takes it to the Prince, “our monarch,” endangering Orgon.

Le fourbe, qui longtemps a pu vous imposer,

Depuis une heure, au Prince a su vous accuser,

Et remettre en ses mains, dans les traits qu’il vous jette,

D’un criminel d’État, l’importante cassette,

Dont au mépris, dit-il, du devoir d’un sujet,

Vous avez conservé le coupable secret.

Valère à Orgon (1835-40, V. vi, p. 104)

[The villain who so long imposed upon you,

Found means, an hour ago, to see the prince,

And to accuse you (among other things)

By putting in his hands the private strong-box

Of a state-criminal, whose guilty secret,

You, failing in your duty as a subject,

(He says) have kept.]

Valère to Orgon (V. 6)

The prince, our monarch, “ennemi de la fraude” (v. 1906, p. 107) sees that Tartuffe is a criminal. Orgon is forgiven. (V. last scene). L’Exempt (an officer) returns the cassette to Orgon as well as the deed to his property.

“The surprise twist ending, in which everything is set right by the unexpected benevolent intervention of the heretofore unseen King, is considered a notable modern-day example of the classical theatrical plot device Deus ex machina.” (See Tartuffe, Wiki2.org.)

The above could have been taken out of my thesis. I studied the pharmakós in six of Molière’s plays. The thesis was entitled: L’Impossible entreprise: une étude sur le pharmakós dans le théâtre de Molière. (The Impossible endeavour: a study of the pharmakós in Molière’s Theatre). In Molière’s comedies, the society of the play may be powerless, hence the use of a deus ex machina. Doublings, as in L’Avare (The Miser), are another recourse. In L’Avare, a second (real and benevolent) father surfaces. Truth be told, Tartuffe goes to prison, but he took little more than he was given. He was given the cassette by Orgon. The cassette comes back to haunt Orgon (V. i; V. 1), which makes him, to a significant extent, a scapegoat.

Feigned Devotion in Dom Juan

- cabale des dévôts

- casuistry

Feigned devotion is a mighty mask. Dom Juan fools Dom Louis, his father, and silences Dom Carlos who is ready to fight a duel that will avenge his sister, Done Elvire. There were real dévots in 17th France, but several members of the cabale des dévôts were faux-dévots. In 17th century France, one could also use casuistry, which could legitimize nearly all sins. Tartuffe reassures Elmire using casuistry. Moreover, there were dévots and faux-dévôts in high places. The Prince de Conti and the Sieur de Rochemont were aristocratic censeurs.

The Alazṓn: the senex iratus and the miles gloriosus

There is recurrence in Molière’s plays and intertextuality, a concept pioneered by Julia Kristeva. I should note that the alazṓn can be a senex iratus or a miles gloriosus. Plautus wrote a Miles gloriosus based on Aristophanes‘ Alazṓn, now lost. Under the heading Alazṓn, two types of blocking character are mentioned: both the senex iratus and the miles gloriosus, the braggart soldier, can be the alazṓn, or blocking character. Dom Juan is a miles gloriosus. I updated a post. We do not see young lovers opposing a heavy father, but Dom Juan is a miles gloriosus and, therefore, an alazṓn.

Varia

- the Baroque

- sources

- “pièce assez mal construite ”

I did not mention Baroque aesthetics in Dom Juan, but he has been called an homme de vent, windy. Nor did I mention sexuality, except briefly, in another post. Dom Juan would like to be an Alexandre, Alexander the Great. The word to conquer puts an emphasis on numbers. Sganarelle tells the peasant-girls that his master is an “épouseur du genre humain,” (II. iv); “the groom of the entire human race” (II.4, p. 27), but there is no eroticism in Dom Juan.

As for sources, most scholars mention Tirso de Molina’s (24 March 1579 – 12 March 1648) Burlador de Sevilla. He is considered the source in what could be described as the “Don Juan cycle,” but Molière’s source may have been Italian. Two of Molière’s contemporaries wrote a Don Juan: Dorimond (1659) and Villiers (1660).[2] Whether they influenced Molière cannot be ascertained. But if Don Juan is a legendary figure, when Molière wrote his Dom Juan, the story had circulated for several years.

Finally, Dom Juan has been considered a poorly-constructed play, une pièce “assez mal construite.”[3] It takes us from grands seigneurs to Pierrot, a peasant who does not want to lose his fiancée to Dom Juan. The play does seem poorly constructed. For instance, I have mentioned the picaresque nature of Molière’s Dom Juan. Picaresque suggests a horizontal line broken, with each encounter, by a vertical line (see Paradigms and Syntagms). It seems Dom Juan and Sganarelle are walking along, meeting artistocrats and peasants, all the way to the supernatural Statue. The trompeur trompé (deceiver deceived) plot formula is circular.

We must stop here. This is our last post on Dom Juan. I should note that Louis XIV banned secret societies in 1666. I doubt he did so to eliminate the Société du Saint-Sacrement. I suspect absolutism precluded secret societies.

RELATED ARTICLES

- See page on Molière

- Casuistry, or how to sin without sinning (5 March 2012)

Sources and Resources

- Dom Juan (Wiki2.org.)

- Libertine (Wiki2.org.)

- Tartuffe (Wiki2.org.)

- Tout Molière.net FR

- Dom Juan (trans. Brett B. Bodemer, 2010) is a digitalcommons calpoly.edu/ publication EN

- Daniel Chandler, Semiotics for Beginners: Paradigms and Syntagms

____________________

[1] Earlier literary criticism used biography to explain a literary masterpiece. Biography is not irrelevant, but it is one of many referents.

[2] Maurice Rat, ed., Molière, Œuvres complètes (Paris: La Pléiade, 1956), p. 895.

[3] Maurice Rat, loc. cit.

Love to everyone 💕

Don Giovanni’s “La ci darem la mano,” encore

Samuel Ramey and Kathleen Battle with Wiener Philharmoniker conducted by Herbert von Karajan

The title page of Le festin de pierre, also known as Dom Juan, the play by Molière, published in Amsterdam in 1683. This is the first publication of the uncensored edition. (Wiki2.org.)

© Micheline Walker

7 March 2019

WordPress

A great second part!!

LikeLike

Thank you Christie.💕

LikeLike

J’ai beaucoup aimé l’article ainsi que la vidéo.

Le baryton chante avec plus de sentiment.

Il est vrai qu’il s’agit d’un extrait d’une représentation.

LikeLike

Il fallait parler du libertinage (érudit). C’était une forme de libre-pensée qui devançait les Lumières. Quant à l’opéra, il vaut mieux en écouter et regarder un extrait. Il s’agit de théâtre chanté. En toute amitié.

LikeLike