Tags

Aarne-Thompson Classification System, An Argosy of Fables, Cherokee Tale, How the Bear lost its Tail, Le Roman de Renart, Tail-Fisher AT 2, The Tales of Uncle Remus

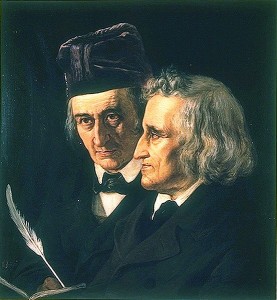

Wilhelm Grimm (left) and Jacob Grimm (right) in an 1855 painting by Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

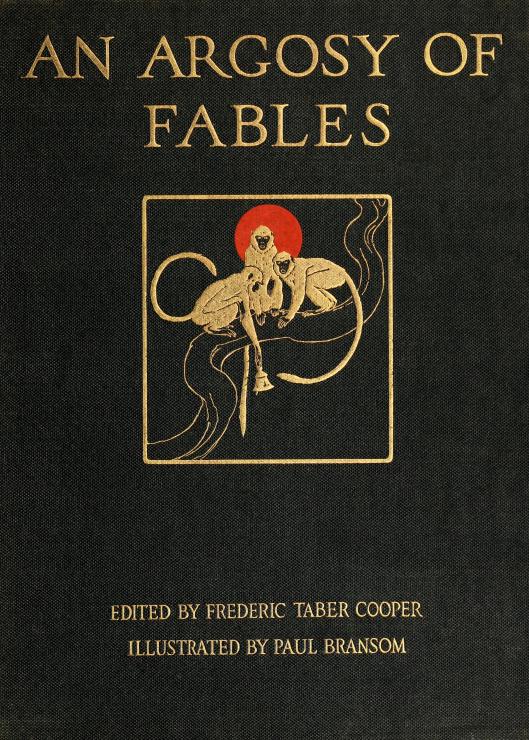

An Argosy of Fables is a Wikisource as well as an Internet Archive publication (please click on Internet Archive), which tells the importance of Frederic Taber Cooper‘s 1921 gift to the world. Both editions contain Paul Bransom‘s lovely illustrations and it would be my opinion that when it was published, in 1921, Frederic Taber Cooper, its editor, was familiar with Finnist folklorist Antti Aarne‘s classification, first published in 1910, extended by Stith Thompson,[1] in 1961, and further revised by Hans-Jörg Uther (2004). It is now entitled the Aarne-Thompson Classification System and constitutes an indispensable tool to folklorists. So is the Perry Index.

The Aarne-Thompson Classification System

The Aarne-Thompson Classification System differs from the Perry Index in that the Perry Index is a classification of Æsopic fables only. For instance, it contains Æsop’s “Fox and Crow,” but also includes La Fontaine’s “Le Renard et le Corbeau” as well as the ‘Æsopic’ “Mice in Council” and La Fontaine’s rendition, “Le Conseil tenu par les rats.”

Conseil tenu par les rats, Marguerite Calvet-Rogniat (Photo credit: Google.com)

As for the Aarne-Thompson Classification System, its scope is much wider. It is a compendium of tales that originate from various countries and are classified according to motifs, plots, and other elements. Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk-Literature is an online publication.

D. L. Ashliman has stated that:

“[t]he Aarne–Thompson system catalogues some 2500 basic plots from which, for countless generations, European and Near Eastern storytellers have built their tales.” (See Aarne-Thompson Classification System, Wikipedia.)

An Argosy of Fables

Similarly, although it is not a classification, An Argosy of Fables is a selection of fables from varied sources, hence my mostly confirmed opinion that Frederic Taber Cooper (1864 – 1937) knew Antti Aarne’s classification, first published in 1910.

According to Wikipedia, “Frederic Taber Cooper, Ph.D., was an American editor and writer, born in New York City, he was educated at Harvard University and Columbia University. He was an associate professor of Latin and Sanskrit at New York University (1895-1902).” (See Frederic Taber Cooper, Wikipedia.)

Dr Cooper also chose translators very carefully. On page [v] of the book, the publishers of An Argosy of Fables “acknowledge the courtesy of Mr. Basil H. Blackwell, publisher of “The Masterpieces of La Fontaine” in permitting the use of Paul Hookham‘s translation of twelve fables by La Fontaine.” It is an Internet Archive publication (see Sources and Resources).

A Cherokee Tail-Fisher Fable

While exploring the contents of an Argosy of Fables, I found an American Indian Fable (fable 469), a Cherokee fable, that could take its beginning in the 13th-century Roman de Renart or Reynard the Fox and its many variants. It would be classified as an AT type 2, Tail-Fisher narrative. In the Roman de Renart, Ysengrin the wolf is the victim of literature’s foremost trickster, Reynard the Fox. Renart tricks Ysengrin the wolf into attaching a bucket to its tail and hanging it down a hole in the ice. The ice hardens and his tail is accidentally chopped off by attackers trying to kill him. (See Le Roman de Renart, Wikisource, p. 55, 9.)

Our Cherokee fable is entitled “How the Bear lost its Tail.” A fox convinces a bear to hold a bucket with his tail down a hole in the ice. The ice hardens and he loses his tail. The rabbit meets the same sorry fate.

The AT 2 Tail-Fisher motif also has affinities with fables and other tales where an animal gets stuck in a hole, which is the case with The Fox with the Swollen Belly (Perry Index 24). Another example is the rape of the Roman de Renart‘s Dame Hersent, the wolf Ysengrin’s wife. She gets caught in the wall of her house and Renart takes advantage of her predicament (branche II).

It is decided at the Lion’s court that Renart should be tried and Bruin is sent to get him. However, having been told he will find honey inside the opening in a tree, he puts his nose down and when the wedges are removed, closing the opening, he loses the skin off his nose escaping. His love of honey also causes Winnie-the-Pooh to eat so much that he cannot leave a house the way he went in.

One could also suggest a degree of similarity between the Tail-Fisher, AT type 2, and both the Æsopic “Fox without a tail” and La Fontaine’s “Le Renart ayant la queue coupée” (V.5). These foxes have no tail, but there is no trickster plot. In the Perry Index, these are numbered 17, but they are not AT type 2 fables. In other words, the main link between the Roman de Renart and “How the Bear lost its Tail” is the tail-fisher episode, a plot found in a Norwegian tale.

Nights with Uncle Remus, Milo Winter (illust.), Gutenberg [EBook #24430]

Pourquoi tales

Yet, “How the bear lost its tail” is also, and perhaps mainly, an etiological or pourquoi tale, related to “How Mr. Rabbit Lost His Fine Bushy Tail,”[2] which is an episode included in The Tales of Uncle Remus by Joel Chandler Harris. The title of our fable is “How the Bear lost its Tail.” In fact, the Tales of Uncle Remus also contain a “Why Brother Bear Has No Tail” (II.21, p. 199), from a motif from Le Roman de Renart or the European Reynard cycle.

Just how these stories crossed the Atlantic constitutes, of course, the larger mystery.

The Coyote

North-American lore features trickster tales, but the trickster is not the fox. In The Tales of Uncle Remus, it is the rabbit, but the coyote is a more important American trickster. In North America, however, if an animal loses a body part, how and why matter more than other questions.

But let us read the Cherokee fable.

“‘THE MORE IT HURTS, THE MORE FISH YOU WILL HAVE.'”

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/An_argosy_of_fables/American_Indian_fables#469

“How the Bear lost its Tail”

AT first all the Bears had long tails. One winter day the Bear met the Fox, who had a fine lot of Crawfish. Being hungry the Bear wanted some too: so he asked the Fox where and how he got his Crawfish. The Fox replied:

“Go and stick your tail down in the water and let it stay there until it pinches you. The more it hurts, the more fish you will have.”

This was what the Bear had in mind to do: so he proceeded down to the lake and made a hole through the ice. Sitting over it, he let his tail hang in the cold water. When it began to freeze, he felt a pain; but as he wanted to catch lots of fish, he did not stir until his tail was frozen fast in the ice. The Fox’s instructions were not forgotten: so he suddenly jumped up in the expectation of getting heaps of fish; but he merely broke his tail off near the body instead. And ever since the Bears have had short tails.

(Myths of the Cherokee, by James Mooney.)

Conclusion

Much of the above has been said in related posts. Moreover, I have already used the video embedded at the foot of this post. But An Argosy of Fables is rather new to me and delightful. I could not resist exploring it further.

My love to all of you. ♥

RELATED ARTICLES

- It’s no skin off my nose (6 October 2014)

- Donkey-Skin: a Tale Labelled “Unnatural Love” (23 May 2013)

- More on the Tail-Fisher (1 May 2013)

- Another Type: The Tail-Fisher (29 April 2013)

- A Motif: Getting Stuck in a Hole (16 April 2013)

Internet Sources and Resources

- Stith Thompson, Motif-index of folk-literature: a classification of narrative elements in folktales, ballads, myths, fables, medieval romances, exempla, fabliaux, jest-books and local legends. (online)

- Joel Chandler Harris, Nights with Uncle Remus, Gutenberg [EBook #24430]

- Le Roman de Renart, Wikisource, p. 55, 9 (online) FR

- An Argosy of Fables, Wikisource (online)

- Paul Hookham‘s Masterpieces of La Fontaine is an Internet Archive publication (online)

____________________

[1] Once known as Stith Thompson’s Motif-index of folk-literature: a classification of narrative elements in folktales, ballads, myths, fables, medieval romances, exempla, fabliaux, jest-books and local legends, an online publication.

[2] Joel Chandler Harris, The Complete Tales of Uncle Remus (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1983 [1955]), p. 80.

Renart and Ysengrin, BnF (Please click on the image to enlarge it.)

© Micheline Walker

4 August 2015

WordPress

Fascinating, Micheline.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Ace Sales & Authors News and commented:

Fabulous post really great writing and research love it 🌹

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much. I’m flattered. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really enjoyed this. Spent time with the Navajo, Hopi, and Crow Peoples. Now I’m in Russia. Hope one day to visit them as well. Thanks

LikeLike

Thank you so much. That story has migrated to many lands, but in North America, it is part of a creation myths. Russia has extraordinary tales.

If you lived with the Navajo, Hopi, and Crow Peoples, you are no doubt well informed.

I thank you for writing.:-)

LikeLike

It’s my pleasure. Yes, I learned a bit from them. It’s interesting now to hear about what the indigenous peoples here say about creation as well. One of my most memorable experiences happened when I was with the Crow. I had an actual vision, it was extremely vivid. But that’s for another time if you are interested.

LikeLike

I’m sure you will learn more. It’s a prime source.

I just added “How the Bear Lost its Tail” to Aboriginals in North America. I love the picture by Paul Bransom.

LikeLike

Yes, agreed.

LikeLike