Tags

French Régime, Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, Phil Fontaine, Prime Minister Stephen Harper, Récollets and Jesuits, Residential Schools

The story of residential schools for Canadian aboriginals has two beginnings. The first is the missionary zeal of Récollets and Jesuits under the French régime. As for the second, it is the establishment of Residential Schools, which began in the 1880s. The very last of which closed its doors in 1996.

In 1966, the Canadian Government opened its Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, first known as the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and, after a fiasco, the White Paper, Amerindians who had been placed in Residential Schools were slowly but progressively rehabilitated and compensated, as per the Royal Proclamation of 1763, their Magna Carta. The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement is the largest ever paid by the government of Canada: 1.9-billion.

The French Régime

- Récollets

- Jesuits

- Jesuit Relations (1632 – 1672)

- The Canadian martyrs

- Black Robe

Our narrative dates back to the French Régime, when France deployed priests to New France, Récollets (c. 1615) and Jesuits, from 1632 to 1763. The Récollets were displaced by the Jesuits. In the case of missionaries, there was no settlement, but martyrs: the eight Canadian Martyrs.

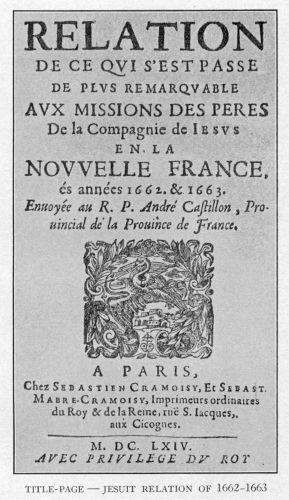

The Jesuit Relations: Martyred missionaries

The Jesuit Relations, the yearly report Jesuit missionaries sent to New France, from 1632 to 1673, tells the story of 8 missionaries tortured to death by Iroquois, except for Noël Chabanel, killed by a Huron. They are René Goupil, Isaac Jogues, Jean de Lalande, Antoine Daniel, Jean de Brébeuf, Noël Chabanel, Charles Garnier and Gabriel Lalemant. All died between 1642 and 1649. Amerindians had their own spiritual beliefs, but were being told otherwise.

Cover of the Jesuit Relations, 1662-1663 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Black Robe, directed by Bruce Beresford (Photo credit: Google Images)

The best 0f intentions

This is a sad story because Récollets and Jesuit missionaries were convinced their religion was the only true religion and that it alone could redeem mankind, guilty of the original sin. In their eyes, they were therefore saving Amerindians.

In 1991, Bruce Beresford directed a film entitled Black Robe. It was based on a novel by Irish-Canadian author Brian Moore. It shows ambivalence on the part of Father Laforgue as to whether or not Amerindians should be converted. I had inserted a few minutes from the film, but the video has been removed. You may never find the time to see this film, but it has to be mentioned. Black Robe is an Australian and Canadian production, filmed in Quebec.

The Red River Colony

Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, who settled the Red River Colony, also had the best of intentions. He wanted to find land for Scottish crofters who were being displaced by their landlords and many of whom were in fact homeless. But that is another story. (See Highland Clearances, Wikipedia.)

Residential Schools

“Residential schools were government-sponsored religious schools established to assimilate Aboriginal children into Euro-Canadian culture.” (See Residential Schools, the Canadian Encyclopedia.)

They were established in 1880 by the Canadian government, and, as mentioned above, the last of these schools closed in 1996, several years after the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development was created, in 1966.

The Hope of Aboriginal Leaders

Instruction: forced, assimilative, incomplete

- poorly-prepared teachers

- an unbalanced curriculum

- the hope of Aboriginal leaders

Persons who taught in residential schools were not necessarily trained teachers. Because these were religious schools, the curriculum often reflected the teachers’ wish to convert aboriginals to Christianity and the concomitant denigration of these children’s spiritual beliefs, the beliefs of their tribes. (See Residential Schools, the Canadian Encyclopedia.)

Consequently, by and large, children attending these schools were seldom provided with the balanced curriculum that could lead to their entering a profession. Where would pupils go upon completion of their studies in residential schools?

Therefore, although some Aboriginal leaders “hoped Euro-Canadian schooling would enable their young to learn the skills of the newcomer society and help them make a successful transition to a world dominated by the strangers” (see Residential Schools, Canadian Encyclopedia), pedagogically, there could not be a genuinely “successful transition.”

In other words, this was not lofty interculturalism, vs multiculturalism, aimed at intercultural competence. (See Interculturalism, Wikipedia.) This was acculturation and students were not immigrants to a new land. They were First Nations, Métis and Inuit students who were on their own land and were not allowed to speak their language among themselves, which was humiliating and could make them feel their language was inferior.

Their education was incomplete. In fact, children spent half the day in the classroom and the other half, working. The Canadian government relied on various Churches (Catholic, Anglican and what would be the United Church of Canada) to fund the schools. In fact,

“[a] First Nations person lost status or ceased being an Amerindian if they graduated university, became a Christian minister, or achieved professional designation as a doctor or lawyer.” (See Indian Act, Canadian Encyclopedia.)

Qu’Appelle Indian Industrial School, Saskatchewan ca. 1885. Parents of First Nations children had to camp outside the gates of the residential schools in order to visit their children. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Abuse

- isolation

- mistreatment

- physical, emotional and mental abuse

- sexual abuse

Residential School, with possible exceptions, were second-rate institutions Aboriginal children were forced to enter. Many were kidnapped and once they were in school, they could not see their parents, nor members of their Reserve for long periods of time. Parents camped outside these schools in the hope of seeing their children. In many residential schools, children were not allowed to go home for the summer holidays. Being separated from their parents and community must have crippled many of these children.

Moreover, pupils were assigned dangerous menial tasks and slept in crowded dormitories. Consequently, the mortality rate among these children was alarmingly high (tuberculosis and influenza [including the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918-19]). They were poorly fed and poorly dressed. Their clothes could not keep them warm when it was cold and cool when it was too warm, which is possible even in Canada. They were physically mistreated and sexually abused, an ignominy from which very few children could recover.

Some Amerindians have fond memories of their years in Residential Schools. There are exceptions to every rule. However, former First Nations Chief Phil Fontaine does not have fond memories of the residential school he was sent to. He has yet to recover fully from mistreatment and sexual abuse. He even approached Pope Benedict XVI regarding this matter. One wonders how Chief Fontaine survived his schooling and grew to prominence. The following link takes you to a short but very perturbing interview.

http://www.cbc.ca/archives/entry/phil-fontaines-shocking-testimony-of-sexual-abuse

The Location of these schools

These schools were located in the central provinces of Canada, the Prairies, as well as Northwestern Ontario, Northern Quebec, and the Northwest Territories. There were no residential schools in the Maritime Provinces where natives had already, though not forcibly, been acculturated. But, although they were not status Amerindians, Métis and Inuit were also locked up in Residential Schools.

According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, an estimated 150,000 First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children were kept in residential schools and, at its peak, in 1930, there were 80 such schools.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763

So what had happened to the Royal Proclamation of 1763?

You may remember that future Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, nicknamed “the little guy from Shawinigan,” proposed assimilation in his White Paper of 1969.

If enacted, the White Paper would have abolished the Indian Act of 1876 and, by the same token, the Proclamation Act of 1763 which still protected Amerindians. Therefore, Amerindians availed themselves of their special status and the then Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development was haunted for years. At any rate, the White Paper was never signed into law.

After the Oka Crisis of 1990, a Royal Commission on Aboriginal Affairs was established.

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau made sure the Canadian Charter or Rights and Freedoms was included in the Patriated Constitution of 1982. In the case of Amerindians, it was and it wasn’t. (See the Constitution Act 1982, Section 35, Indigenous Foundations, UBC).

Section 25 reads as follows:

25. The guarantee in this Charter of certain rights and freedoms shall not be construed as to abrogate or derogate from any aboriginal, treaty or other rights or freedoms that pertain to the aboriginal peoples of Canada including

(a) any rights or freedoms that have been recognized by the Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763; and

(b) any rights or freedoms that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired.

Section 35 reads as follows:

35. (1) The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.

(2) In this Act, “aboriginal peoples of Canada” includes the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada.

(3) For greater certainty, in subsection (1) “treaty rights” includes rights that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired.

(4) Notwithstanding any other provision of this Act, the aboriginal and treaty rights referred to in subsection (1) are guaranteed equally to male and female persons.

Note the Notwithstanding and, for clarification, See:

http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home/government-policy/constitution-act-1982-section-35.html

As noted above, the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement of 2007 is the largest to be negotiated in Canadian history: $1.9-billion. Prime Minister Stephen Harper also presented a formal public apology to Chief Phil Fontaine in 2008. “Nine days prior, the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established to uncover the truth about the schools.” (See Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, Wikipedia.)

I am sorry our Canadian Aboriginals were practically imprisoned in Residential Schools and that it happened in my lifetime, but Canada has apologized and all is well. Would that the suffering of Amerindians did not go beyond Residential Schools, but there is more to tell.

With kindest regards to all of you. ♥

Prime Minister Stephen Harper presents the government’s official apology for residential schools to then-Assembly of First Nations Chief Phil Fontaine on June 11, 2008. (Photo credit: the Winnipeg Free Press)

Residential Schools

How sad to read about the plight of the Aboriginal children in schools. You have really provided a thorough look at the issues here and thank you for educating readers

LikeLike

It is sad Christy. But, there is some comfort in remembering that there was less awareness of psychology, political science, etc. in the past. Often, people did not know they were ruining lives. However, we know. We can be agents of change, one person at a time.

I must admit that preparing this post was an eye-opener. The testimonial given by Phil Fontaine could have been the post. The “developers” are the current hurdle.

With best wishes,

Micheline

LikeLiked by 2 people

Black Robe looks very interesting. Have you seen the Australian film Rabbit Proof Fence? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabbit-Proof_Fence_%28film%29 Canada was not alone in its injustice towards Aboriginals.

LikeLike

No Gallivanta, so that will be on my “to do” list. By and large, we have not been kind to our aboriginal populations. The best for governments could be to say a collective: “Today is the first day of the rest of my life.” We cannot revive the dead: 4,000 children (conservative estimate), but we build the road to the future.

Phil Fontaine’s testimony is very disturbing.

Take care Gallivanta

Micheline 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on [Modern Times].

LikeLike

Thank you very much. It’s an honour.

LikeLike