Tags

Aimé du Boisguy, assignats, Civil Constitution of the Clergy, Confiscation, de-Christianisation of France, Dr Gemma Betros, separation of Church and State, Talleyrand, unsuspected consequences, War in the Vendée

Portrait présumé d’Aimé du Boisguy, peinture de Jean-Baptiste Isabey, 1800.

The Church of France during the French Revolution

- Chouannerie

- War in the Vendée (1793-1796)

The above portrait is presumed to be that of Aimé Casimir Marie Picquet, chevalier du Boisguy, or Bois-Guy. Aimé Picquet du Boisguy (15 March 1776, Fougères, Ille-et-Vilaine – 25 October 1839, Paris) was a Chouan (literally an “owl,” also called hibou in French), a monarchist from the Fougères area of Britanny (see Chouannerie, Wikipedia). Boisguy seems much too young to have fought against the French Revolutionary Army (active from 1792 until 1802).

When Boisguy was 15, he started fighting. At the age of 17, he was aide-de-camp (chief-of-staff) to Charles Armand Tuffin de la Rouërie[i] who played a role in the American Revolutionary War. By the age of 17, Boisguy was in fact a leader of the Chouans in what is now the Fougères commune of Britanny, then called le pays de Fougères (the country of Fougères). By the age of 19, he was a general. Boisguy was fearless, but not reckless. He therefore survived chouannerie uprisings.

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy

- The Civil Constitution of the Clergy

- The levée en masse

However, this post is not about the chouannerie,[ii] except indirectly. It is about the demise of the Church of France. Chouannerie uprisings were royalists uprisings that lasted beyond 1800 and, as such, they were also Catholic uprisings. Absolutism demanded that France be ruled by one king, that Catholicism be its only Church and French, its only language. There was considerable anti-clericalism in France. It had become widespread during the Enlightenment and the growth of Freemasonry also dictated laïcité in government. Yet, even among Chouans, many opposed the repression of the Church. Moreover, the War in the Vendée (1793-1796), was caused, first, by the Civil Constitution of the Clergy (July 1790) and, second, by the levée en masse (23 August 1793) (mass conscription). In fact, as we will see in a later post, it was also caused by the persecution of the clergy. (See War in the Vendée, Wikipedia.)

“The first signs of real discontent appeared with the government’s enactment of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy (July 1790) instituting strict controls over the Roman Catholic church.”[iii]

“However, the massive uprising of an important part of the West and the transition to counter-revolution was mostly caused by the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the levée en masse decided by the National Convention.”[iv]

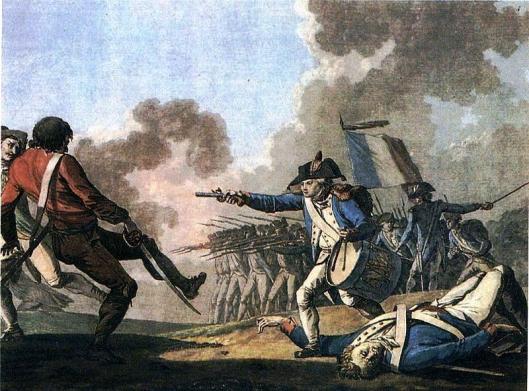

The War in the Vendée (1793-1796) was a royalist uprising that was suppressed by the republican forces in 1796 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Henri de La Rochejaquelein fighting at Cholet, 17 October 1793, by Paul-Émile Boutigny (See Battle of Cholet, Wikipedia.)

The Main Events

What follows is a quotation, but I have underlined certain phrases: see Civil Constitution of the Clergy, Wikipedia.

- On 11 August 1789 tithes were abolished.

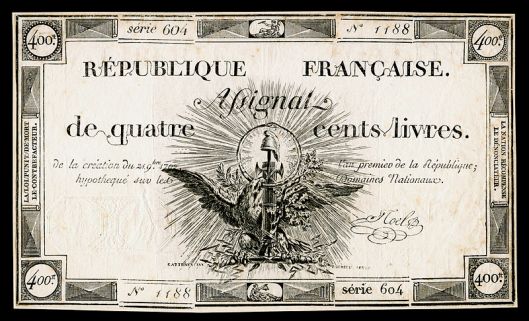

- On 2 November 1789, Catholic Church property that was held for purposes of church revenue was nationalized, and was used as the backing for the assignats.

- On 13 February 1790 (some sources give the date as 11 February for example), monastic vows were forbidden and all ecclesiastical orders and congregations were dissolved, excepting those devoted to teaching children and nursing the sick.

- On 19 April 1790, administration of all remaining church property was transferred to the State.

Assignats worth 400 pounds and 15 pennies (sols=sous) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Civil Constitution of the Clergy: Motivation

What follows is a quotation, but I have underlined certain words: see Civil Constitution of the Clergy, Wikipedia.

- The French government in 1790 was nearly bankrupt; this fiscal crisis had been the original reason for the king’s calling the Estates-General in 1789.

- Church lands represented 20–25% of the land in France. In addition the Church collected tithes.

- Owing, in part, to abuses of this system (especially for patronage), there was enormous resentment of the Church, taking the various forms of atheism, anticlericalism, and anti-Catholicism.

- Many of the revolutionaries viewed the Catholic Church as a retrograde force.

- At the same time, there was enough support for a basically Catholic form of Christianity that some means had to be found to fund the Church in France.

- Presumably, another factor, at least indirectly, was Jansenist rejection of the cult of kingship [the Divine right of kings, Wikipedia] and absolutism.

The Assignats: the main motivation

Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-PérigordThe assignat was legal tender between 1789 and 1796 and it would appear that bankruptcy, and little else, led to the confiscation of the wealth of the Church (biens de l’Église). The ultimate law, the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, was passed on 6 February 1790, but the idea of confiscating the goods of the Church, les biens de l’Église, dated back to 10 October 1789. On that day, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord,[v] or Talleyrand, a priest, a bishop (l’évêque d’Autun) and a representative of the Church during the meeting of the Estates-General of 1789, suggested that the government fill its empty vaults by confiscating the wealth of the Church, which it did on 2 November 1789. The biens de l’Église became biens nationaux (national property) as would, later, the biens des émigrés, the property of émigrés.

The Revolution: a Life of its Own

Ironically, neither the de-Christianisation of France during the French Revolution nor the downfall of the monarchy had been the objectives of the 577 representatives of the Third Estate who, on 20 June 1789, assembled in an indoors jeu de paume, a tennis court, when they discovered they had been locked out of a meeting of the Estates-General. The 576 signatories of the Tennis Court Oath favoured a constitutional monarchy.

Had the monarchy been a constitutional monarchy, the Third Estate would have played a role in the government of France. In other words, France would have been a democracy, as was England. But the Estates-General had not convened since 1614, which is what representatives of the Third Estate opposed. Moreover, the Church was vulnerable because members of the clergy were exempt of taxation, as were members of the nobility. The Church also collected tithes (la dîme). So, to a certain extent, the very radical French Revolution was a variation on a familiar theme, “no taxation without representation.” (See Civil Constitution of the Clergy, Wikipedia.)

On 20 June 1789, the 577 delegates of the Third Estate, who had taken refuge in a jeu de paume, wanted no more than representation. The 576 signatories of the Tennis Court Oath did not attack the Church, except indirectly. However, the Third Estate supported both the Church, the First Estate, and the nobility, the Second Estate, through burdensome taxes. So both the Church and the nobility were parasites. Nevertheless, it remains unlikely that the signatories of the Tennis Court Oath suspected the destruction of the Church. (See Civil Constitution of the Clergy, Wikipedia). I am inclined to agree with the following statement by Dr Gemma Betros:

“The wholesale destruction of Catholicism had been far from the minds of the nation’s representatives in 1789, but financial concerns, when combined with external and internal threats, eventually made a full-scale attack on the Church and all connected with it a necessity for a Revolution that demanded absolute loyalty.”[vi]

Conclusion

It is difficult to explain the Concordat of 1801, between Napoleon and Pope Pius VII, and Chateaubriand‘s Génie du Christianisme without the information provided in this post and a forthcoming post. I should also note that the Civil Constitution of the Clergy should be inserted in a much wider debate: the separation of Church and State in France. (See 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State, Wikipedia.)

To be continued…

____________________

[i] A cavalry officer who served under the American flag during the American War of Independence, as did La Fayette.

[ii] Uprisings in twelve departments of Western France, but mainly Brittany. Chouannerie uprisings are named after Jean Cottereau, or Jean Chouan, a nom de guerre, one of two royalist brothers.

[iii] “Wars of the Vendée.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2014. Web. 02 May. 2014. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/625053/Wars-of-the-Vendee>.

[iv] “Chouannerie,” Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chouannerie

[v] André Castelot, Talleyrand ou le cynisme (Paris : Librairie académique Perrin, 1980), pp. 64-65.

[vi] “Gemma Betros examines the problems the Revolution posed for religion, and that religion posed for the Revolution.” History Today. Published in History Review (2010).

Johann Sebastian Bach (31 March 1685 – 28 July 1750) Toccata & Fugue D Minor, BWV 565 © Micheline Walker

2 May 2014

WordPress

© Micheline Walker

2 May 2014

WordPress

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The words in your content seem to be running off the screen in Opera. I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to do with internet browser compatibility but I thought I’d post to let you know. The design look great though! Hope you get the problem solved soon. Kudos|

LikeLike

Thank you for letting me know about a technical. I will contact WordPress. Thank you for writing to me.

Salutations,

Micheline

LikeLike