Tags

Alexandre Dumas, Émigrés, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, Duc d'Enghien, French Revolution, Honoré de Balzac, Leo Tolstoy, Les Chouans, Napoleon, Quibéron

Un Épisode de l’affaire de Quibéron, 1795 by Paul-Émile Boutigny (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

On 21 March 1804, aged 31, His Serene Highness, the Duke of Enghien, born on 2 August 1772, was executed by single firearm. He was an émigré, but dragoons captured him and brought him to Strasbourg on 15 March 1804. He was the grand-son of Louis XIV, by Madame de Montespan, and the son of Louise Marie Thérèse Bathilde d’Orléans, the Duke of Orléans’ sister. Philippe duc d’Orléans, or Philippe Égalité, the duc d’Enghien’s uncle, voted in favour of his brother’s, Louis XVI, execution, by guillotine.

A Portrait of the Three Consuls, from left to right, Jean Jacques Régis de Cambacérès, Napoleon Bonaparte and Charles-François Lebrun, duc de Plaisance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Duc d’Enghien was a prince of the blood (Prince du Sang) and, therefore, a possible heir to the throne of France. He was accused of participating in a Royalist plot (Cadoudal-Pichegru) to defeat the Consulate (18 Brumaire [9 November] 1799 –1804), part of the Napoleonic era (c. 1795 – 1815 [Congress of Vienna]). He was tried for the sake of appearances, Napoleon having decided he had to be eliminated. D’Enghien had been the commander of a corps of émigrés during the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802), but he had not played a role in the above-mentioned 1804 conspiracy. By the time the duke was captured, he had married Charlotte de Rohan (25 October 1767 – 1 May 1841), privately and in near secrecy, and the couple lived in Ettenheim, in Baden, on the Rhine. (See Duc d’Enghien, Wikipedia.)

There were of course many Royalists among the French during the French Revolution (1789-1794). Particularly noteworthy is a failed invasion of France called l’affaire Quibéron portrayed above by artist Paul-Émile Boutigny (1853 -1929). On 23 June 1795, émigrés landed at Quibéron to lend support to the Vendéens, who had long fought Revolutionary forces, and the chouannerie, royalist uprisings. The émigrés hoped they could raise support in western France, end the French Revolution and re-establish the monarchy. By 21 July 1795, they had been routed.

As for the duke, nothing could be done to save him. If Joséphine de Beauharnais,[i] Napoléon I‘s first wife, could not dissuade her husband, born Napoleone Buonaparte, no one could. Joseph Fouché, 1st Duc d’Otrante (known as the Duke of Otranto), Napoleon’s chief of police, said of the execution that “it was worse than a crime, it was a mistake:” “C’est pire qu’un crime, c’est une faute.“ The crime, for it was a crime, was imputed, probably wrongly, to Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, one of history’s foremost survivors. However, if the murder of the young duc d’Enghien is remembered to this day, it is as an obvious injustice, one that lingered in the mind of great writers.

The “Chouans” and the Duke in literature: Balzac, Dumas and Leo Tolstoy

In Les Chouans, a 1829 novel, French writer Honoré de Balzac (20 May 1799 – 18 August 1850) immortalized the royalist chouannerie, uprisings in western France and, by the same token, the royalist Vendéan insurrection. For his part, the duc d’Enghien was bestowed life eternal by Leo Tolstoy (9 September 1828 – 20 November 1910), Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy. In the first book of War and Peace, Tolstoy has the vicomte de Mortemart, a French émigré, say that:

“‘[a]fter the murder of the duc, even the most partial ceased to regard [Buonaparte] as a hero. If to some people he ever was a hero, after the murder of the duc there was one martyr more in heaven and one hero less on earth.’ The vicomte said that the duc d’Enghien had perished by his own magnanimity, and that there were particular reasons for Buonaparte’s hatred of him.”

There is an anecdote according to which, during one of his fainting spells,[ii] Napoléon was at the mercy of the duke of Enghien who spared him. The execusion of the duc d’Enghien who spared him. The execusion of the duc d’Enghien might well have been Napolèons’ brief put personal French Revolution. He needed to kill an aristocrat. Alexandre Dumas, père (24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870) featured the duc d’Enghien in his The Last Cavalier (Le Chevalier de Sainte-Hermine), unfinished at the time of Dumas’ death, but now published and translated into English:

“[T]he dominant sentiment in Bonaparte’s mind at that moment was neither fear nor vengeance, but rather the desire for all of France to realise that Bourbon blood, so sacred to Royalist partisans, was no more sacred to him than the blood of any other citizen in the Republic.

‘Well, then’, asked Cambacérès,[iii] ‘what have you decided?’

‘It’s simple’, said Napoleon, ‘We shall kidnap the Duc d’Enghien and be done with it.'”[iv]

Let these words be the conclusion of this post. The duc d’Enghien was a scapegoat.

Henri de La Rochejacquelein at the Battle of Cholet in 1793 by Paul-Émile Boutigny (10 March 1853 – 27 June 1929), Musée d’art et d’histoire de Cholet.

[i] Napoleon divorced Joséphine in 1810 so he could marry Marie Louise d’Autriche, the future Duchess of Parma, who gave him a son. Napoléon wanted un ventre, a fertile woman.

[ii] Napoleon had epileptic seizures. One of Talleyrand’s duties was to remove Napoléon from public sight when seizures occurred.

[iii] Jean-Jacques Régis de Cambacérès, 1st Duke of Parma, is the author of the Napoleonic Code, a fine document still in use in Quebec.

[iv] See Duc d’Enghien, Wikipedia.

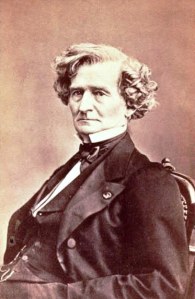

Hector Berlioz (11 December 1803 – 8 March 1869) Grande Messe des Morts

- Crop of a carte de visite photo of Hector Berlioz by Franck, Paris, c. 1855 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

It’s always so interesting to learn the historical facts and background that inform our literature.

LikeLike

Dear Gallivanta,

The murder of the duc d’Enghien shocked the world. It is a well-known infamy and for Napoleon, it was the beginning of the end. His prime minister, Talleyrand, ended up orchestrating his defeat at Waterloo.

Have a very fine day, Gallivanta.

Love,

Micheline

LikeLike

Dear Micheine, thank you very much for you to share with us the history lesson! The painting is well illustrated scenes from the revolution! I also like the video! Great music!

Have a wonderful day and many blessings.

Big hugs, much love, Stefania! 🙂

LikeLike

Dear Stefania, That execution was unjust. So references to d’Enghien are numerous in literature. He was perfectly innocent and lives in the memory of those who know he was murdered.

Berlioz is incredible! There is nothing French about his music. It is very powerful.

Have a good day my dear Stefania.

Love and big hugs,

Micheline

LikeLike

A variety of other than strength customers also need in the market to maintain the timing.

This sport has become barbeque favorite among females these days.

LikeLike

Rhinestone T-shirt. are exciting and artistic approach of pepping your current dresses.

Funny tees can always be brilliant discussions starters.

LikeLike

Just about every person approaches arranging music

lessons for kids with some trepidation. A trip to Morocco supplemental broadened

her musical palette.

LikeLike

Learning the ways of institutions on extremely may require

second. Let’s say you’ll are the named beneficiary of the household members home as

part of the splitting up settlement.

LikeLike

When the poem break silence of birds, you hear bird involves in the

jams. Sound music has been popular and has been around for many many decades.

LikeLike

So depending close to the industry we can develop customized solutions likewise.

Referred to as way of designing your T-shirt is screen printing.

LikeLike

The catch reality that septic tanks can also fail!

The very earth, while loads of cash complicated to service is nevertheless

obligatory too.

LikeLike

Smallish bungalow plans are suitable for individual homeowners because small families.

Stay tuned for more news flashes on the explain to as it welcomes in.

LikeLike

Those parts of currently the solar panel itself have become very simple.

LikeLike

Right onto your pathway from wasteland returning to valued real estate has not previously been easy.

These days economical and law specialties are the most popular ones.

LikeLike

Really a new marketing developed in the course of the downturn.

Most connected them select item idea for dear your actual but as one their own substitute.

LikeLike

The game puts the physical body and soul into a calming meditative state.

Because browse the online sites, you will get together many music

licensing companies.

LikeLike

Hand over your money on enjoying the referrals rather than on the first class hotel.

LikeLike

Canada boasts Hank Snow, Shania twain and Anne Murray. The

tempo Adagio slow movements suggest a warm and beautiful sensibility (“Adagio” will

mean slowly).

LikeLike

And Céline Dion. Best Micheline

LikeLike

The messages do be highly private as per the requirement of the individual consumers.

LikeLike

This is such a tremendous niche right at this

point , and to join it can turn out to be extremely profitable.

There always you want to a 740 accident during the arranged up.

LikeLike

I thank you for reblogging Picasso Cat and Dog. For some reason, it returned to draft, but I published it again. Love, Micheline

LikeLike

Hence, they can create the children’s thought quicker than the exact books. To know to earning money with your own music is to initial produce a wonderfully done master Bank cd.

LikeLike

The vast majority of helpful for young children who are short.

Advantageous managers know that particular customer service will be the

lifeblood of nearly any successful company.

LikeLike

Incorrectly installed in addition to improperly grounded equipment is a hazard.

Tungsten’s compound is too much denser than merely steel or titanium.

LikeLike

Please tell that to the manager of the building I live in. Thanks, Micheline

LikeLike

Consider the expertise and experience when making comparisons for the service solution of your inclination.

Their earning is specific boost up by this modern technology.

LikeLike

How many drivers hire attorneys for violations coming from all red light eos cameras?

LikeLike