Tags

Acadian, Évangéline, Cajuns, Deportation of Acadians, Georgia, Gregg Howard, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Pourquoi tales, Reynard, Tail-fisher, Thirteen Colonies, Uncle Remus

Photo credit: Google

RELATED ARTICLES:

- Another Motif: The Tail-Fisher (michelinewalker.com)

- Reynard the Fox, the Itinerant (michelinewalker.com)

- Évangéline & the “literary homeland” (michelinewalker.com)

- Évangéline & the “literary homeland” (cont’d) (michelinewalker.com)

- Uncle Remus & Tar-Baby (michelinewalker.com)

In a post published in 2011, I traced Reynard the Fox’s steps from various European countries to Georgia, US, where he is featured in Joel Chandler Harris‘ (9 December 1848 – 3 July 1908)[i] Uncle Remus, His Songs and His Sayings: The Folk-Lore of the Old Plantation. It would be my opinion that deported Acadians told Reynard stories and Æsopic fables to the Black population of Georgia when they were finally allowed to leave the ships in which they sailed down the east coast of the current United States. With the exception of Georgia, the Thirteen Colonies were not interested in providing a home to Catholics. Acadians expelled in the second wave of the Grand Dérangement, c. 1857-58, were sent to England and France, but may also have moved to Louisiana.

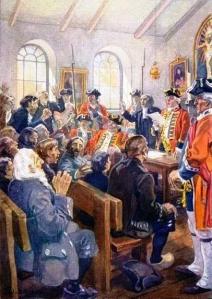

The expulsion of the Acadians took place during the French and Indian War (1755-1763). British officials posted in Boston deported 11,500 Acadians to prevent this French-speaking population and their Amerindian allies from helping the increasingly dissatisfied citizens of the Thirteen Colonies gain independence from Britain.

Acadians lived in the present day Maritime Provinces of Canada: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. They also lived in the state of Maine, US. Many fled to Canada where they lived in “P’tites ‘Cadies” (small Acadies) or were rescued by Amerindians when British soldiers were rounding them up. Moreover, many of the deportees whose ships sailed down the coast of the eastern US,[ii] found their way back from Georgia to the current Canadian Maritime provinces.[iii]

However, among those who arrived in Georgia, US, a large number travelled to Louisiana, then a French colony, and their descendants are called Cajuns. These are the Acadians who, in my opinion, told Reynard stories and Æsopic fables to the coloured population of Georgia whose status they shared. However, in The Tales of Uncle Remus, the trickster ceases to be the fox. In America, with a few exceptions, the tricksters will be the rabbit (Uncle Remus) and the coyote. In Uncle Remus, Brer Rabbit is led by Brer Fox into fishing with his tail. As for our Cherokee tale, told in a video inserted at the bottow of this post, Fox is not only leading the rabbit but trying to play a trick on an American “trickster,” the rabbit.

Évangéline, a Tale of Acadie

The deported Acadians were put aboard ships in a pêle-mêle fashion. Husbands were separated from wives, parents from children and couples from one another. American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (27 February 1807 – 24 March 1882) immortalized this tragic event in an epic poem entitled Évangéline, published in 1847. Longfellow‘s poem, Évangéline, a Tale of Acadie is a Gutenberg ebook (number 2039) that one can access by clicking on Évangéline. Longfellow was motivated to write his Évangéline by American novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne (4 July 1804 – 19 May 1864) and he may have been helped by Thomas Chandler Haliburton.

The poem tells the story of a fictional, and now mythic, Évangéline whose family name is Bellefontaine. She is separated from her betrothed, Gabriel Lajeunesse, during the Great Upheaval (le Grand Dérangement) and spends years looking for him. She finds him in Philadelphia where, as an old woman, she is working as a Sister of Mercy tending to the victims of an epidemic. Her beloved Gabriel dies in her arms. (See Évangéline, Wikipedia.)

Charles William Jefferys (25 August 1869 – 8 October 1951) Photo credit: commons.wikimedia.orgBrer Rabbit replaces Brer Fox as Trickster

But let us now return to Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox.

Interestingly, as mentioned above, the Tales of Uncle Remus include the tail-fisher motif in that a rabbit’s bushy tail is shortened when it gets stuck in the hole through which he is fishing, trying to catch fish, as did Brer Fox. Although Brer Fox may have intended for Brer Rabbit to lose his tail, in Uncle Remus, the tail-fisher motif is mostly a “pourquoi” tale, the French word for “why.” Such tales are origin stories or etiological tales.

Joel Chandler Harris devised an eye dialect to represent a Deep South Gullah. To summarize the story, it tells of Brer (Brother) Rabbit who is. walking down the road shaking his long, bushy tail when he meets Brer Fox walking along with a string of fish. They spend time with one another (“wid wunner nudder,”) and Brer Fox says that he got the string of fish at the Baptizing creek. Brer Fox tells Brer Rabbit that he sat there with his tail in the water and that, in the morning, he discovered he had caught many fish.

“…en drap his tail in de water en set dar twel day-light, en den draw up a whole armful er fishes, en dem w’at he don’t want, he kin fling back.”

(…and dropped his tail in the water and sat there until daylight, and then drew a whole armful of fish, and then those he did not want, he could throw back in the water.)

So Brer Rabbit tries to catch fish in the same manner, but the water freezes and when he tries to pull his tail it is no longer there: “en lo en beholes, whar wuz his tail?” (and lo and behold, where was his tail?).

“One day Brer Rabbit wuz gwine down de road shakin’ his long, bushy tail, w’en who should he strike up wid but ole Brer Fox gwine amblin’ ’long wid a big string er fish!W’en dey pass de time er day wid wunner nudder, Brer Rabbit, he open up de confab, he did, en he ax Brer Fox whar he git dat nice string er fish, en Brer Fox, he up’n ’spon’ dat he katch urn, en Brer Rabbit, he say whar’bouts, en Brer Fox, he say down at de babtizin’ creek, en Brer Rabbit he ax how, kaze in dem days dey wuz monstus fon’ er minners, en Brer Fox, he sot down on a log, he did, en he up’n tell Brer Rabbit dat all he gotter do fer ter git er big mess er minners is ter go ter de creek atter sun down, en drap his tail in de water en set dar twel day-light, en den draw up a whole armful er fishes, en dem w’at he don’t want, he kin fling back. Right dar’s whar Brer Rabbit drap his watermillion, kaze he tuck’n sot out dat night en went a fishin’. De wedder wuz sorter cole, en Brer Rabbit, he got ’im a bottle er dram en put out fer de creek, en w’en he git dar he pick out a good place, en he sorter squot down, he did, en let his tail hang in de water. He sot dar, en he sot dar, en he drunk his dram, en he think he Gwineter freeze, but bimeby day come, en dar he wuz. He make a pull, en he feel like he comin’ in two, en he fetch Nudder jerk, en lo en beholes, whar wuz his tail?” Chapter XXV

Conclusion

This particular tale is an example of the tail-fisher motif, Aarne-Thompson: AT type 2. However, I have also found the tail-fisher motif in a the Cherokee tale, mentioned above and told in the video inserted below. As is the case in The Tales of Uncle Remus, our Cherokee tale is, first and foremost, an etiological or “pourquoi” tales, rather than a trickster tale but the fox remains the trickster. However, of particular interest here is that The Tales of Uncle Remus are an American version of the Reynard stories and Æsopic and that they may have been transmitted to the Black population of Georgia, US, by Acadians deported in the first wave of the expulsion, when the ships carrying Acadian deportees sailed down to Georgia.[v] However, were it not for Joel Chandler Harris, we may never have known why the Black population of Georgia knew about Reynard and various Æsopic tales.

As for our Cherokee tale, it is a Reynard story inasmuch as Fox wants to get back at the Rabbit because the Rabbit is a tricskter. Moreover, the dramatis personae also includes a Bear, Bruin or Brun, bearing a Cherokee name. In the Cherokee tale, the Bear helps pull the Rabbit out of the hole in the ice, which is when the Rabbit loses his tail.

It could be, therefore, that the Glooscap myths include one tale about a rabbit who lost its tail.

_________________________

[i] Joel Chandler Harris was an American journalist, fiction writer, and folklorist. (See Joel Chandler Harris, in Wikipedia.)

[ii] To my knowledge, the history of the Expulsion has not been fully investigated. It would appear that the Acadians were expelled in two waves, rather than all at once, and that some ships sailed towards Europe, to England and France. Moreover, Paul Mascarène (c. 1684 – 22 January 1760), a descendant of French Huguenots émigrés, may have been among the officers who organized or suggested the Expulsion or Deportation.

[iii] Antonine Maillet’s novel entitled Pélagie-la-Charrette is about Acadians returning to their former territory.

[iv] Canada: Cultures and Colonialism to 1800 (HIST 4508). WordPress

[v] See Micheline Bourbeau-Walker, « La Patrie littéraire : errance et résistance », Francophonies d’Amérique, <http://www.erudit.org/revue/fa/2002/v/n13/1005247ar.html?vue=resume>.

_________________________

![Expulsion of the Acadians WordPress [iii]](https://michelinewalker.files.wordpress.com/2013/05/acadian-expulsion-image.jpg?w=529&h=378)

Dear Micheline,

I tell many trickster tales, and I love to hear you tell about their origins. I knew a Cajun storyteller, J.J. Reneaux, who was just amazing. I knew that “Cajun” was derived from “Acadian,” but really enjoyed the historical background. Everything seems so much richer and more meaningful when you know its story. Thanks for another wonderful post.

Love,

Naomi

LikeLike

Dear Naomi,

Trickster tales are classics and researching their origins is very pleasurable. I’m glad these animals are not in pain when they lose their tail: it’s always the tail. I visited Louisiana several years ago. Its population is one of the most colourful I have met and the food was extraordinary.

Thank you for writing and take good care of yourself.

Love,

Micheline

LikeLike

Very fascinating history for me. I had no idea about the Acadians.

LikeLike

Dear Gallivanta,

Nor did I know about the Acadians until I taught a course on animals in literature. Many of my students were Acadians and at least one was in part Amerindian. She told me about Glooscap. I was in Nova Scotia and consequently in Acadian territory and Ameridian territory. Together, we figured it out. The Acadians knew both Reynard the Fox and La Fontaine’s fables. My next step is to present my results to the American Folklore Association or publish these results in their quarterly: The Journal of American Folklore. It’s the best hypothesis. A short article will suffice and I will have to ackowledge that WordPress published those results.

My dear Gallivanta, I thank you for writing and take good care of yourself.

Love,

Micheline

LikeLike

I wish you well with publication,

LikeLike

Thank you Gallivanta. It may work, it may not. Fortunately, the internet allows me to continue to do a litte research and some teaching an to communicate with others.

A good day to you dear Gallivanta.

Love,

Micheline

LikeLike

Very interesting… but still bizarre for me to read you in English even though it’s my 2nd language… 🙂 Amitiés toulousaines & my very best, Mélanie – catlover, à la vie, à la mort… 🙂 Michel Fugain et le Big Bazar – Les Acadiens:

– – –

Mille merci pour tes haltes @playground! 🙂

LikeLike

Boujour Mélanie et amitiés canadiennes ! Il m’a été difficile de commencer à écrire en anglais et je fais des fautes, mais je voulais me servir d’une langue mieux connue que le français. C’est quand même bizarre, car j’ai consacré toute ma vie à l’enseignement du français.

Bises,

Micheline

LikeLike